With spring in full swing, we’re taking a look at some of the must-read debuts of 2025 from Doubleday. From a hilarious social takedown to atmospheric historical fiction, these novels will jump straight to the top of your TBR pile.

Hear more about these exciting new books from the authors themselves below.

To be in with a chance of winning a bundle of Doubleday debuts, enter the competition here by midnight on the 27 April (UK entries only).

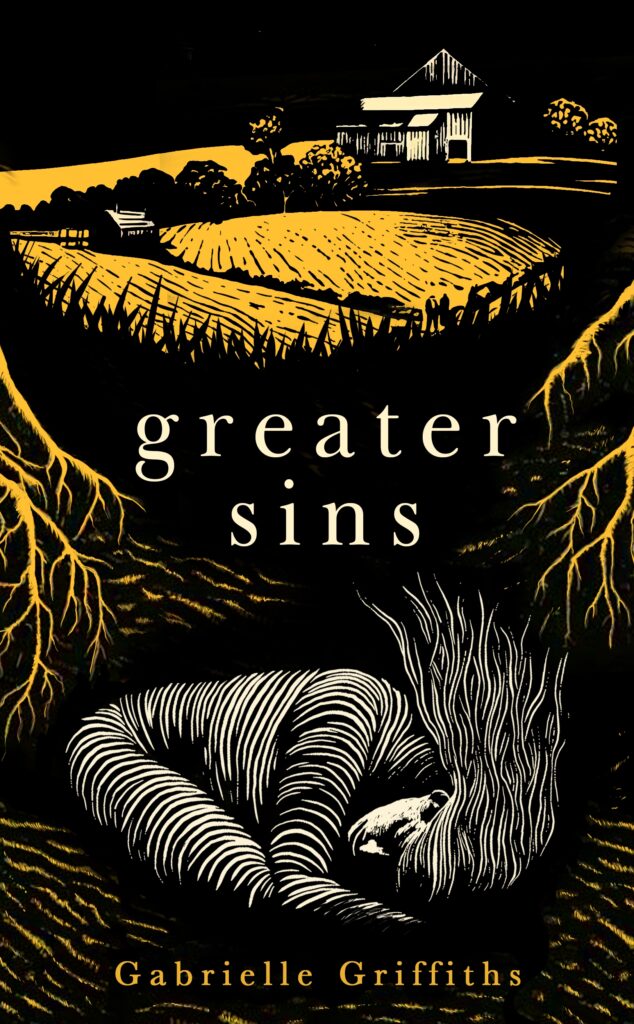

When the preserved body of a woman is discovered in a bog near an isolated village community, rumours begin to fly. To some, the body is an omen, heralding misfortune to come. To others, hers is a story waiting to be told.

Gabrielle Griffiths says:

“Greater Sins was inspired by a remote region of north-east Scotland near where I grew up – a thriving farming community which fell into near-abandonment after WWI and a run of harsh winters. I began to think about the type of people who might have lived there through choice – or otherwise – and what happens when something upends life in an isolated community (in the novel’s case, the discovery of a perfectly preserved body in a peat bog). I wanted to explore how such an event, coloured by superstition and religion, class and gender, might become a means of deflecting responsibility and placing blame elsewhere. I think a lot of what it means to be human transcends time, and I hope that my cast of characters from 1915 – charming but self-loathing Johnny and ever-hopeful cynic Lizzie – will resonate with readers today. Now more than ever, we need stories as sources of hope and fellowship. It’s surreal being published – there’s a lot of excitement but also anxiety (I think “author” and “control freak” are pretty much synonymous), but it’s an incredible honour to have other people read my words, and that’s the bit I hold on to – what joy if another person is moved by them!’

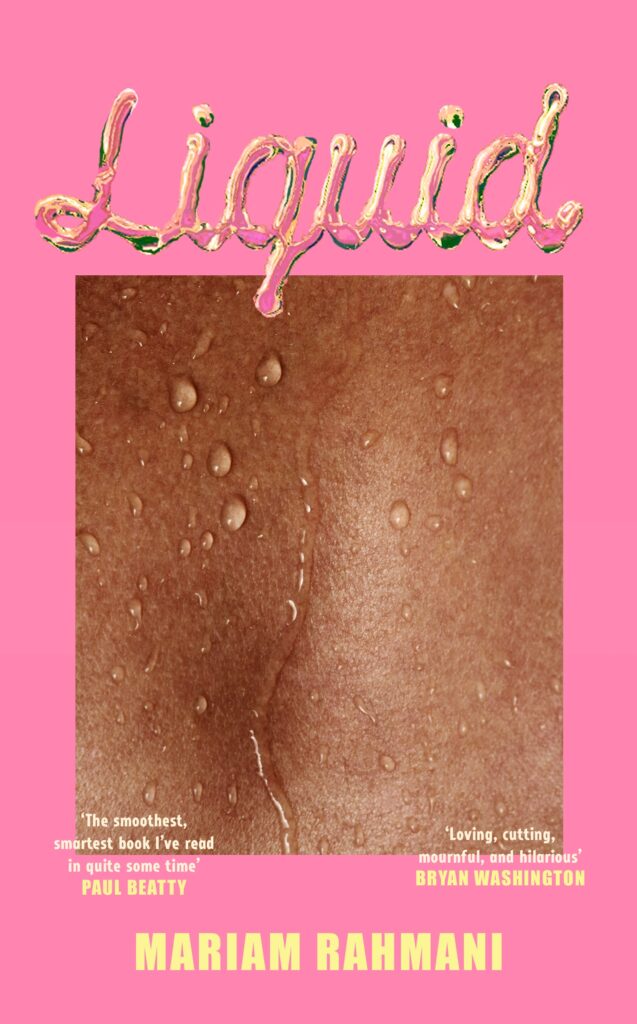

Our protagonist always believed herself to be the smartest person in the room. But a couple of years on from earning a fancy PhD, she’s still broke, single and stuck in a job in LA going nowhere. One option remains: marry rich. She commits herself to 100 dates in as many days, but before long reality hits, taking her – and her marriage project – to Tehran.

Mariam Rahmani says:

“Liquid was born in a frenzy of frustration. I was writing and translating, floated by flimsy term-to-term teaching appointments, and I didn’t want to give up on the thinking life. On the other hand, I felt that our society was doing just that. And it’s not just the life of the mind that’s being sacrificed to the bottom line. In a city like LA especially, middle-class existence altogether is fast disappearing. Americans today are watching the rich get richer, while the naked fact that you are a woman, or BIPOC, or queer (much less “and”) likely means you’re earning less on the dollar than white men. Worldwide, income polarization is only getting worse – it’s no coincidence that lampooning the rich has become its own genre. Meanwhile gender equity proves an ever-receding horizon. In my experience humour can whet the blade of critique, offering a way to encounter what seem like unsurmountable social ills – racism, sexism, etc. – head on. Love, on the other hand, is hope. When the basic premise of Liquid came to me – a queer adjunct professor trying to marry rich – I knew I wanted to write something that talked about hard stuff but answered more softly. This novel is that whisper.”

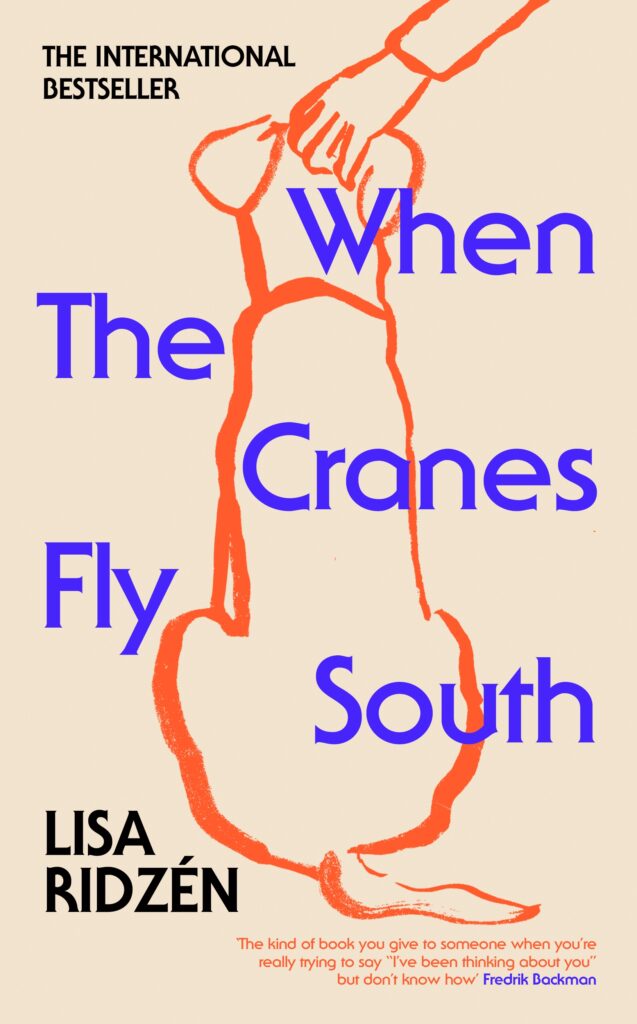

The Swedish number one bestseller and voted Book of the Year by booksellers. This unforgettable debut about a man, his son, and a dog is a story about all the things we leave unspoken and the power of stories to bring us together again.

Lisa Ridzén says:

“The first seed of the idea for When the Cranes Fly South came to me when I found the notes from my grandfather’s care team. When people grow old in Sweden, they are entitled to home care, which means they are visited by people who help them with medication, cooking, cleaning and personal hygiene so that they can live at home for as long as possible. Often the staff write small notes to each other and to the elderly person’s family about how the person is doing, what they’ve eaten, information about medication and even small reflections. When I went through these short daily observations about my grandfather, I realized that I wanted to write a story from an elderly person’s perspective. I wanted to show how ageing forces a person into vulnerability and to capture the emotional discrepancy between how the person felt inside as opposed to how other people viewed them.

Writing about Bo, I drew inspiration from this and from my own work with the elderly. These visits often became the chance for them to open up and share stories about their lives and inner world. My hope is that readers will feel they grow close to Bo and his life in his cabin with Sixten the dog and the home care team. That they will experience warmth, joy and sorrow as they share in his memories and his everyday life.”

An unnamed narrator who has fled a set of friends she despised, who bring out the very worst in her and each other, finds herself once more sitting at their dinner table for a single, hideous evening.

Zoe Dubno says:

“The narrator of my novel Happiness and Love returns to New York after a few years away from her vapid, transactional and exploitative cultural elite friends. Within a week of being back in New York, she’s all the way back, sitting at a dinner party surrounded by everyone she was trying to run away from. Without speaking a word out loud she entertains herself from her perch on a very nice and expensive sofa with a silent, tender, merciless takedown of her ex-friends and of herself.

I wrote this book from a feeling of grossed-out loneliness about the cultural avant-garde I’d encountered on both sides of the Atlantic. A part of me wanted to write about these people who jetted around the world to half-glance at some artwork and stay at five-star hotels and pat themselves on the back for changing the world, to laugh at them, to expose them as hypocritical villains. But I also wanted to show how easily someone could be enticed by that world and build their life around this scene. As a first-time author I’m looking forward to the surreal experience of walking past my own book in a shop – finally, me! a commodity – and I’m freaked out (with gratitude) that so many people will spend a few hours with me and my writing.”

You have never read a coming-of-age story like this before. Ruth is a literary debut about a woman born into an anabaptist community, whose life we follow from childhood to middle age. But Ruth is not particularly good at being within this community, she has her doubts. Powerful, funny, life-affirming and unusual, this is a sardonic novel that asks: is this what it is to be happy?

Kate Riley says:

“In my twenties, I lived for a time in a closed religious community, where I spent some of the happiest days of my life and marvelled daily at the scope for love and specificity in an environment with so many rules and so little access to mainstream culture. When I left that community, I missed a world to which I had lost access, a way of living of which there was no public evidence. I tried to commission a journalist friend to write a profile of the community – offered to pay her regular rates for a piece that only I would read, just to have a record – but she wisely refused, and I was forced to invent the story myself, as a means of returning to, expanding and communicating the feeling of being there. I can’t remind readers of a place they’ve never been, but I hope my book feels true and strange in pleasing proportion; that it points at things worth noticing, worth wonder.”