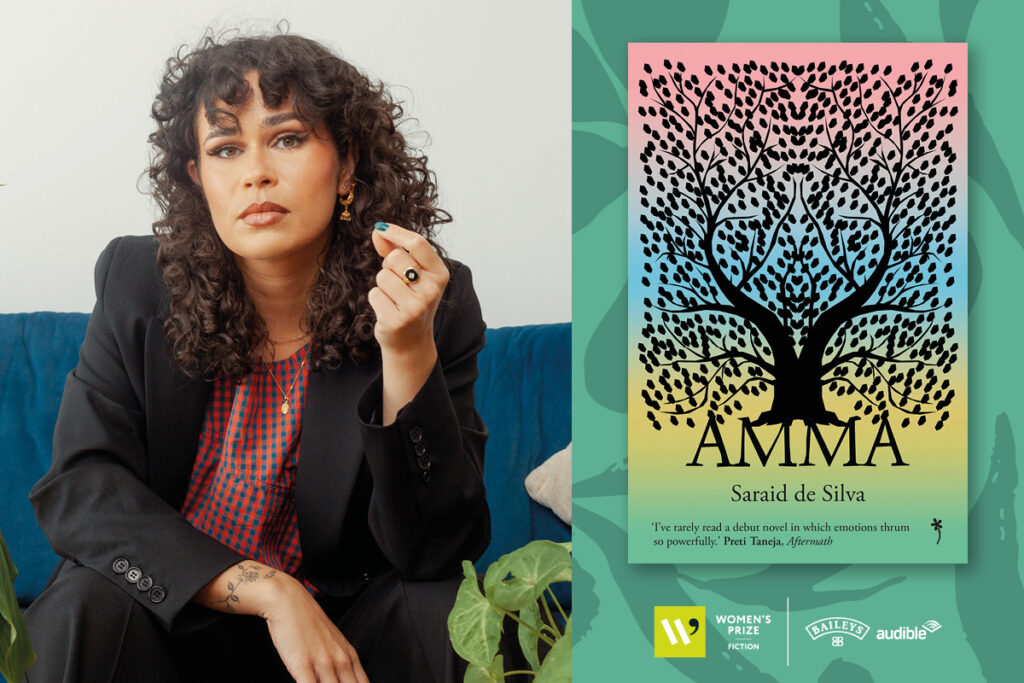

Set in Sri Lanka, Singapore, New Zealand, Australia and London, Saraid de Silva’s Amma is a multi-generational novel about family, displacement and queerness, and how the past lives with us forever.

Longlisted for the 2025 Women’s Prize for Fiction, 2025 judge Deborah Joseph says: ‘I didn’t want this book to end. It’s a multi-generational story about a Sri Lankan woman, her daughter and granddaughter, spanning decades and countries from Sri Lanka to New Zealand. There are so many powerful scenes which have stayed with me long after I finished it and shows how societal judgements on women have changed over time.’

To find out more about the book we spoke to Saraid about her inspirations, writing process and favourite books.

How would you describe your book to a new reader?

I would like to say only that the book is about three generations of South Asian women in one family. I always feel like my relationship to a book as a reader is very personal so if someone asks me directly I kind of withhold what I think the book is about to let them decide for themselves. If pushed, I might say that to me it is a book about migration, rage, and revenge.

What was the idea that sparked your novel?

When my Gran died I realised I would never fully know her. It made the grief worse, I think. We only see certain sections of the lives of the people who raise us. That’s what made me write a book where three lives take place (kind of) in parallel, where they overlap, glance off or mess with each other even though they happen in different decades and countries.

Which part of the book did you write first? Was there a moment that clicked a lot of things in place or where you felt the strands of the book started to come together?

The part I wrote first happens quite far into the book and takes place in a church beside a Catholic primary school. There wasn’t really a moment where things clicked into place while writing, more so while I was editing. I did keep hoping for the moment where I would feel the manuscript was really singing. In reality it was more that I occasionally liked a sentence I had written. It’s not as exciting as the idea of watching the book form in front of me or feeling confident in what I was doing, but I couldn’t zoom out and see it like that till I was almost through it.

Which part of the book was the most fun to write? Which was the most challenging?

I liked writing physical things because although I could see them (car crashes, big and small violences), I had no idea how to make the mechanics visible to the reader. So that was both fun and quite intimidating. I had to rework those bits so many times.

What is the best piece of writing advice you have ever received?

This advice wasn’t given to me personally, but Bolu Babalola tweeting, ‘In writing, I always get blocked when I try to start grand rather than honest’, was both inspiring in the moment I read it and just useful to remember when I was struggling with some moment in my own work. I printed it out and stuck it next to my desk.

Which female author would you say has impacted your work the most?

What is your favourite book from the Women’s Prize library and why?

Piranesi by Susanna Clarke and Detransition, Baby by Torrey Peters on the list in 2021 was so major. They were my two favourite books I read that year and I still think about them often. How perfectly formed and surprising Piranesi is as a story, how many worlds there are inside the relationships in Detransition, Baby. Those two books have really stuck around for me.

Could you reveal a secret about your creative process?

Not writing in the weekends has helped me so much. Generally making sure there are times when I leave the work alone. It’s nice to rest and it also means I see what I want to correct clearly when I return to the manuscript. Basically designating time to write and time to rest has been invaluable.