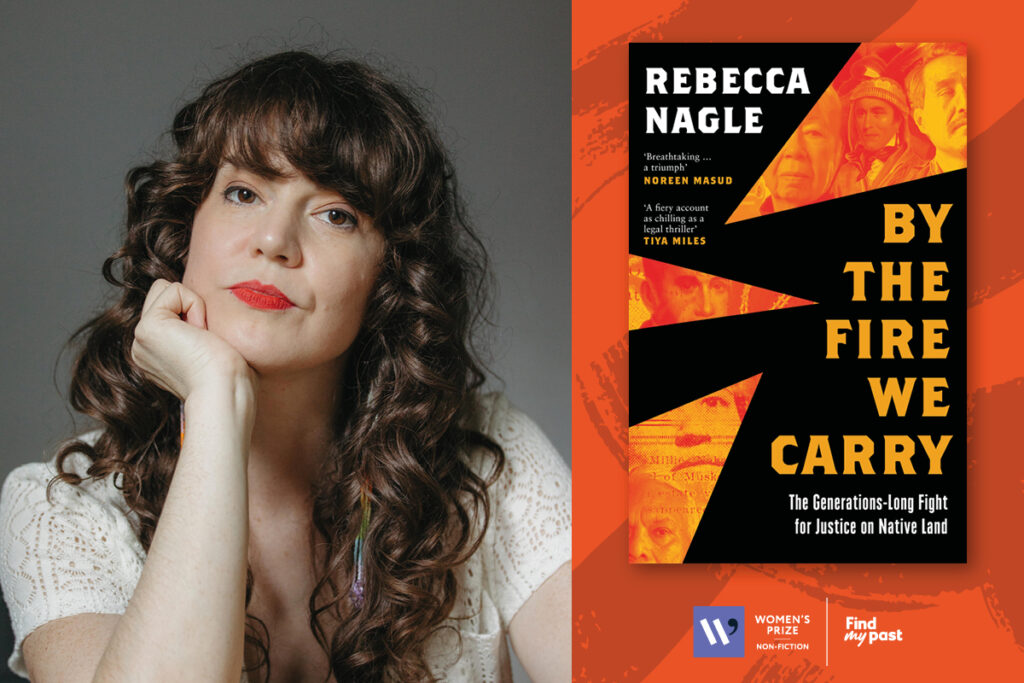

By the Fire We Carry by Rebecca Nagle braids together the story of the forced removal of Native Americans in the nation’s earliest days with a small town murder in the 1990s.

Longlisted for the 2025 Women’s Prize for Non-Fiction, judge Elizabeth Buchan says: ‘Reportage and history collide in this account of a contemporary Oklahoma murder court case which triggered a reappraisal of the historic forced removal of Native Americans onto treaty lands. Eye opening and shocking, the author unpeels a narrative of exploitation and injustice.’

To find out more about the book we spoke to Rebecca about her writing, research and current reads.

How would you describe your book to a new reader?

Before 2020, American Indian reservations made up roughly 55 million acres of land in the United States. Nearly 200 million acres are reserved for National Forests—in the emergence of this great nation, our government set aside more land for trees than for Indigenous peoples. By The Fire We Carry tells the story of how a small-town murder turned into a legal battle over a reservation in Oklahoma and ultimately resulted in the largest restoration of tribal land in the U.S. In the 1830s Muscogee people were rounded up by the US military at gunpoint and forced into exile halfway across the continent. At the time, they were promised this new land would be theirs for as long as the grass grew and the waters ran. But that promise was not kept. When Oklahoma was created on top of Muscogee land, the new state claimed their reservation no longer existed. Over a century later, a Muscogee citizen was sentenced to death for murdering another Muscogee citizen on tribal land. His defense attorneys argued the murder occurred on the reservation of his tribe, and therefore Oklahoma didn’t have the jurisdiction to execute him. Oklahoma asserted that the reservation no longer existed. In the summer of 2020, the Supreme Court settled the dispute. Its ruling that would ultimately underpin multiple reservations covering almost half the land in Oklahoma, including my own Cherokee Nation.

Did you have any revelation moments when writing your book? When the narrative and your objectives all fell into place?

Some of the most powerful moments in researching the book came from encountering my family members in their own words. By the 1830s, Georgia wanted Cherokee land – and after Cherokees refused to go – decided to terrorise the tribe until they had no choice. My ancestors became part of a small fraction who thought the only way for Cherokees, as a people and a nation, to survive was to move west. What had changed was not their desire for Cherokees to remain in their homelands; it was their hope. What surprised me in the primary sources was how consistently and passionately they pleaded their case. For 8 years before their deaths, their position did not change. “Did we act in such emergencies as these for our private comfort, we might choose to die here, and bury our bones in the land of our fathers,” they wrote in one letter. “Where white people might desecrate our tombs with the ploughshare of the farmer. But when we think of our children,” they argued, “[we] will, at all hazards, seek freedom in the far regions of the West.” Eventually, unable to convince their countrymen, the Ridges took the desperate measure of signing a treaty against the will and government of the Cherokee people.

The other voices I encountered in the primary documents were the majority of Cherokee citizens who opposed the treaty my ancestors signed. The Cherokee people had voted down a removal treaty—through public meetings and their elected representatives—multiple times. After the treaty was signed, they organised massive petition drives to protest its ratification and enforcement–collecting signatures from nearly every Cherokee man, woman and child. By circumventing democracy, the treaty denied “Cherokees the right to think for themselves,” they argued. The Cherokee people, they wrote, should decide their own fate. Eventually, I came to believe that my ancestor made the wrong choice for the right reason. They were motivated by protecting the future existence of our tribe, but wrong to go around the will and government of the Cherokee people.

What is the one thing you’d like a reader to take away from reading your book? Is there one fact from the book that you think will stick with readers?

The biggest take-away for readers is that the United States committed genocide. This is a problem not just for Indigenous nations, but our democracy. Historians still debate whether or not the United States committed genocide against Indigenous peoples. Genocide, as defined by the United Nations, is the “intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnical, racial or religious group” by one or more acts of physical violence. The Cherokee word for our removal is ᏗᎨᏥᎢᎢᎸᏍᏔᏅᎢ. It literally means “when they drove us.” It’s the same word we use to talk about herding animals. To prepare, the army split logs, drove them into the ground lengthwise, and built 25 open-air stockades. On May 23, 1838, 7,000 U.S. soldiers and militiamen went out into the hills and valleys of Cherokee Nation to round the people up. Cherokees, startled by bayonets in their gardens or kitchen, were not allowed to collect any possessions. When a deaf man did not understand the militia men’s orders, they shot him. Over 15,000 people were herded into the camps. The army was woefully unprepared to feed and house their thousands of captives. By fall, Cherokees had buried 2,000 of their fellow citizens. As a newspaper reported at the time, “that is one eighth of the whole number, in less than four months.” When Cherokees marched west that winter death followed. Although the exact number is unknown, one missionary estimated 4,000 people died between the camps and removal–a quarter of the total population. In our self-conception, America is a beacon of democracy for the rest of the world. Even when our founding sins are recognized, we like to believe things have gotten better. The story we tell ourselves is one of progress. In reality, our government committed genocide. It has never reformed itself or changed its laws to prevent such atrocities from happening again.

How did you go about researching your book? What resources did you find the most helpful?

The research was heavy. To understand what our ancestors survived I read first hand accounts of racial violence. Since these accounts were often written by the soldiers, bureaucrats and even criminals who inflicted that violence the documents were not only traumatic, but also racist. But just as often the research was soul-filling. To learn the history of a small church or rural community I collected photocopies from people’s personal archives. I interviewed a former police officer in my car in a WalMart parking lot. I stood in the places my ancestors stood when they made decisions that changed the course of history. I got to meet the people, see the places and hear the stories that made the history I wanted to tell real to me.

For my research, I started with books. Of course I was reading for information like timelines, people and key events, but I was mostly paying attention to what was in the back of the book: the citations. What primary sources were historians using? Where should I dig for more information? After scouring bibliographies and asking around, I made an initial list of primary sources I wanted to get my hands on. The list had two main parts: specific documents like a letter or congressional record and larger collections or archives like the Draper papers or the pages of the Cherokee Phoenix.

Because the Trail of Tears and the history of removal is well-researched, some sources were available in published volumes, like the Moravian Records translated by Rowena McClinton (a journal by German missionaries who ran a school my ancestor attended) or Bending their Way Onward, a volume of letters and army records related to the removal of Muscogee Nation edited by Christopher Haveman. A lot of records were on microfilm. Due to the pandemic, many archives were not open to the public. On the other hand, more institutions were willing to digitize primary sources. For example, the records of one christian group whose missionaries became very involved in Cherokee Nation are housed at Harvard’s Houghton Library. They scanned the handwritten letters and sent them to us.

Which female non-fiction author would you say has impacted your work the most?

What is the best piece of writing advice you have ever received?

The best advice I ever got was to take breaks and step away from the work. Writing a book is a marathon, not a sprint. Sometimes when you have spent a lot of time with the material, you stop seeing the forest for the trees. For me, setting the writing down for a period of time and coming back to it helps me read it with fresh eyes and see things I missed before.

Is there a non-fiction book you recommend all the time? If so, what is it and why do you recommend it?

The Warmth of Other Suns by Isabel Wilkerson. The book tells the sweeping history of the great migration, but through the shifting perspectives of three main characters. I think it is a great example of a story-driven way to tell a complex and deeply-researched history.

What are you currently reading?

I am currently reading Never Whistle at Night, a collection of Indigenous short stories and The Message by Ta-Nehisi Coates

By the Fire We Carry: The Generations-Long Fight for Justice on Native Land

by Rebecca Nagle

Find out more