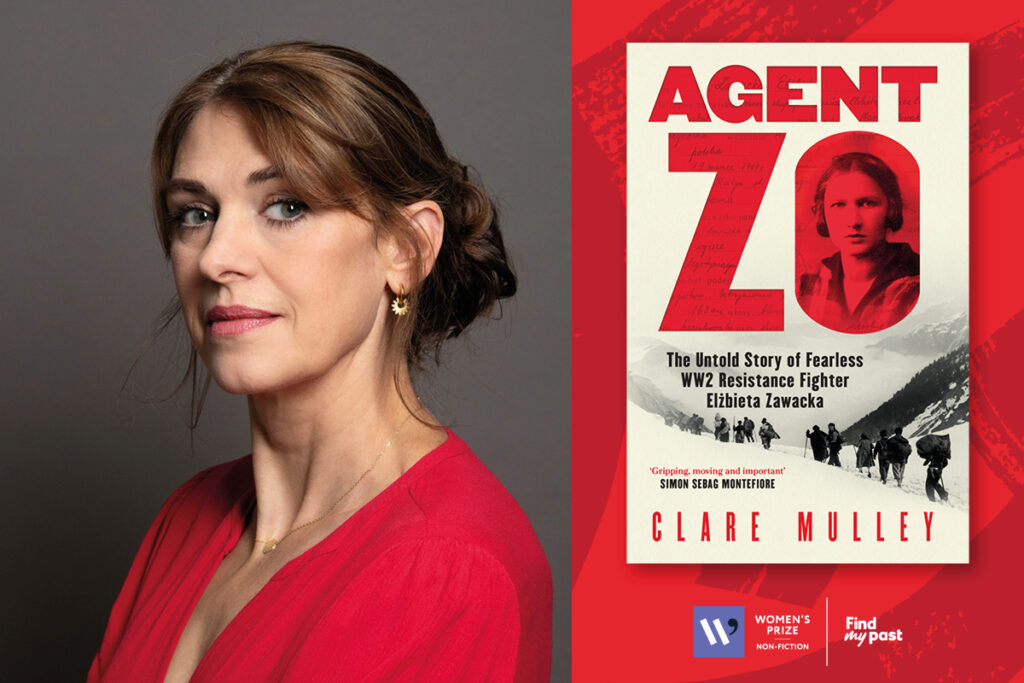

Agent Zo by Clare Mulley tells the previously untold story of Elżbieta Zawacka, a World War Two Resistance Fighter.

Longlisted for the 2025 Women’s Prize for Non-Fiction, Chair of judges Kavita Puri says: ‘A masterclass of biographical writing, Elżbieta comes alive through the pages in this gripping and compulsive read. This is a definitive and well researched account about a woman we should all know about.’

To find out more about the book we spoke to Clare about her writing, research and current reads.

How would you describe your book to a new reader?

Agent Zo tells the story of courageous resistance fighter Elżbieta Zawacka, aka ‘Zo’. During the Second World War, Zo was the only woman to parachute from Britain to Nazi-German occupied Poland. There, while being hunted by the Gestapo, she set up a women’s intelligence network, smuggled microfilm across the Third Reich and, as the only female member of the Polish elite special forces, ‘The Silent Unseen’, she played a key role in the Warsaw Uprising. Yet the post-war Communist regime imprisoned her and ensured her remarkable story remained hidden for over 40 years. Now, through new archival research and exclusive interviews with people who knew and fought alongside Zo, Clare Mulley brings this forgotten heroine back to life, transforming the way we see female agency during and after the war.

Did you have any revelation moments when writing your book? When the narrative and your objectives all fell into place?

I first heard Zo’s name when I interviewed a female veteran of the Warsaw Uprising some years ago. There are so many powerful stories of Polish women fighting for the freedom of their country and themselves that I simply filed Zo away with them. There were two moments when I realised her story could be the main vehicle to tell a broader history. Firstly when I discovered she had continued to fight on after the war, both against Marshal Law and then with the Solidarity movement. I realised then that her life is at the heart of a century of Polish history, and Poland’s long road to freedom. However, it was only when I realised she was also fighting for women’s rights that I knew I had to write the book. ‘Men,’ she once wrote, ‘keep talking about their own participation. And yet this complete passing over in silence of women’s work, stalled with sentimental or praising cliché… is tantamount to falsifying the history’. Zo not only secured the legal military status of women in Poland’s resistance Home Army, thereby potentially saving thousands of lives, she also saved their stories from being forgotten by establishing a secret archive – for which she was later arrested by the communist regime. I knew then that this was a book that could explore important issues as well as recount real heroism and drama.

What is the one thing you’d like a reader to take away from reading your book? Is there one fact from the book that you think will stick with readers?

There are two key take aways. Firstly, when we think of resistance in the Second World War we tend to think about France and western Europe. There is great history there, some of which I have written about. But we are much less good at remembering the resistance in Eastern Europe, which started earlier and was hugely significant. This history is particularly resonant today. Secondly, women in the resistance and female special agents tend to be remembered for their courage, in some cases sacrifice and, all too often, their beauty. (This last could actually be a disadvantage, as beauty makes a face memorable.) We are much less good at considering the value of these women’s achievements. Zo was among the most effective female special agents and resistance fighters. If I could add a third point, it would be that in Britain we tend to think freedom came to Europe at the end of the war in 1945, but Poland was left with a Soviet imposed communist regime. Resisters like Zo kept fighting for their freedom until 1989!

How did you go about researching your book? What resources did you find the most helpful?

Agent Zo required a vast amount of research. Because the Polish government was exiled in London during the war, there are three small but wonderful Polish archives here, plus the National Archives at Kew, the Imperial War Museum etc. But most research was undertaken over two visits to Poland, at their National Archives, and many independent archives including at various museums, the convent where Zo twice hid during the war, and the university where she taught afterwards. The most notable archive was the one that Zo set up herself in Toruń, which has typed and handwritten files in Polish on thousands of women who served, all of which needed translating. Interviews with dozens of people ranging from a woman who as a teen had shared Zo’s prison cell, several veterans of the Warsaw Uprising and the families of other resisters, to Zo’s later students, niece, and carers, and even Polish President Lech Wałęsa. I drew the line at parachuting from a plane myself (though did go up in a glider for an earlier book), and I interviewed a young para on that, as well as an expert on steam trains, and various other specialists. Also lots of reading primary and secondary books, press, journals and online articles and archives.

Which female non-fiction author would you say has impacted your work the most?

This is hard. I read voraciously, male and female authors – and there are far more men writing in my field. If I have to pick one female author, possibly Anne Sebba whose research is impeccable and writing both authoritative and humane. Sebba’s Les Parisiennes turns the better-known Paris tapestry over to reveal another weave of fascinating and sometimes long-hidden threads, something she is doing again in her new book on the women’s orchestra in Auschwitz. However my work is also inspired by historians including Wendy Lower, journalists like Laura Cumming, and novelists from George Eliot to Elizabeth Fremantle!

What is the best piece of writing advice you have ever received?

Some of the above, but one other piece that worked particularly well for me was simply to stop writing for the evening somewhere where you know you have more to say. When you return, it is much easier to pick up the narrative when you have the scene in your mind, than it is to start again from the blank page of a new chapter or new line of thought. And once you are writing, it is easier to continue.

Is there a non-fiction book you recommend all the time? If so, what is it and why do you recommend it?

One of my favourite war-time memoirs is by Between Silk and Cyanide, by Leo Marks. Marks was the head of coding for SOE, and served from Britain but trained many of the special agents sent behind enemy lines. So he has a good tale to tell, but what elevates the book is his very immediate and witty writing style. ‘She had a very firm grip, especially with her eyes’ he wrote of meeting one agent, and the building they were in was ‘a large private house which tried to ramble but hadn’t the vitality etc’. I recommend the book to everyone as it is such a pleasure to read, even if you are not that interested in the subject, but particularly to other aspiring writers as it demonstrates that serious history can be engaging rather than ‘worthy’.

What are you currently reading?

Anne Sebba, The Women’s Orchestra of Auschwitz which I will be reviewing for The Spectator. Richard Evans’ Hitler’s People and Katrin Himmler’s The Himmler Brothers for research. On dog walks and in the car, Jo Baker’s Longbourn on Audible.

Agent Zo: The Untold Story of Courageous WW2 Resistance Fighter Elżbieta Zawacka

by Clare Mulley

Find out more