Wild Thing: A Life of PauI Gauguin by Sue Prideaux re-examines a trailblazing, yet controversial post-impressionist artist, casting new light from fresh research.

Longlisted for the 2025 Women’s Prize for Non-Fiction, judge Emma Gannon says: ‘I read this book in a day. The pages come alive with colour, magic and incredible storytelling, from a wealth of new research. It reaches into every corner — friendship, grief, creativity, insanity, work, family — to create a memorable portrait of a complicated figure and artistic trailblazer.’

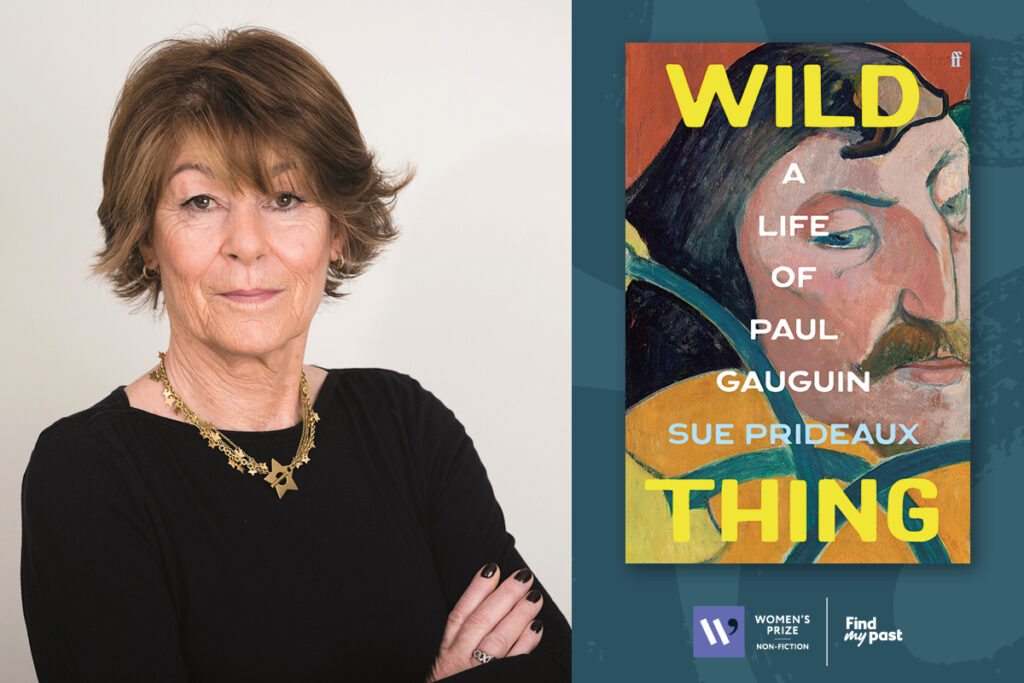

To find out more about the book we spoke to Sue about her writing, research and current reads.

How would you describe your book to a new reader?

A myth-busting biography of a very great painter, the first full biography of Paul Gauguin for thirty years, based on a wealth of evidence recently come to light. It’s a fascinating life. Growing up in a palace in Peru, fighting in the Franco-Prussian War, making and losing a fortune, digging the Panama Canal, becoming an artist and exhibiting in the Impressionist shows; living with Vincent Van Gogh, who painted his famous ‘Sunflowers’ to decorate Gauguin’s bedroom. Finally, when Gauguin gets to Tahiti, exposing the corruption of French colonial rule, championing the indigenous people, demanding fairer taxation and treatment for the Polynesians and acting as their lawyer in Court. It was a surprise to find Gauguin’s strong belief in sexual equality. His grandmother Flora Tristan was a fierce fighter for women’s rights, she was much admired by Karl Marx. Gauguin cherished her published writings all his life. He actively encouraged the women in his circle, including his wife, to find fulfillment through independence.

Did you have any revelation moments when writing your book? When the narrative and your objectives all fell into place?

The most important revelation was that I had to write this book. I had no intention of doing so in 2019 when I visited the exhibition of Gauguin’s portraits at London’s National Gallery. The show provoked a tremendous reaction. Gauguin was a colonialist paedophile who spread syphilis throughout the South Seas. He should be cancelled; it was even suggested his paintings should be burned. I have always loved Gauguin’s work. Coming out of writing my book about the philosopher Nietzsche, how could I live in the dishonest position of loving the art and hating the man? I needed to find out the truth. First: syphilis. In the year 2000, four of his teeth were discovered, examined by the Human Genome Project in Cambridge and other labs around the world. No trace of syphilis was found. Next, I investigated the question of under-age girls. The age of consent in France and the colonies at the time was thirteen. Pretty average for around the world. In the United States, for instance, it varied between ten and twelve except in the State of Delaware, where it was seven. As I was finishing writing Wild Thing in June 2023, Japan raised the age from 13. I am not quoting these statistics to excuse Gauguin’s behaviour, they disgust me but they do provide the context for the 1890s. Gauguin had three serious sequential relationships. Tehamana, the best known, was long supposed to be thirteen but a recently discovered birth certificate shows she was probably fifteen. Within these relationships the local custom was for sexually experienced girls to be offered by their families. After a couple of weeks, the girl went home to decide if she wanted to return to her new husband. Tehamana came back. There was no financial advantage: Gauguin in his hut struggling to make a living from his art was no richer than the average villager. There was no control or coercion: Tehamana, like his other lovers, was free to come and go and to take other lovers as she pleased. When Gauguin went to Paris for two years, Tehamana married but when Gauguin came back she went to live with him for a couple of week, for old times’ sake. It suggests affection. It seemed to me important that these facts be known; not to condemn, not to excuse, but simply to shed new light on the man and the myth. And so, to my own surprise, I found myself writing Gauguin’s biography.

What is the one thing you’d like a reader to take away from reading your book?

Gauguin’s belief in synthesis connecting all cultures and races, both in art and in life. In art, he believed that what is now called cultural appropriation was inevitable and positive, summing up his position by saying ‘The little wooden rocking horse in my nursery is descended from the horses of the Parthenon’. One of the first pictures he painted in Tahiti was ‘Hail Mary’ (1891) showing a Polynesian Mary carrying a Polynesian Christ child. When it was exhibited in Paris, it caused a scandal: a non-white Holy Family! It was not until 1951 that a Papal encyclical made it permissible to represent such a thing. Which is ridiculous if you think where Mary and Joseph came from.

How did you go about researching your book? What resources did you find the most helpful?

Eventually, after lockdown, I got to visit Polynesia and it was invaluable (as well as wonderful) to see how the light falls in that place and how it relates to the paintings, as well as visiting the places he lived and painted, and interviewing people. As a biographer I always walk the walk. You can achieve so many insights into the work and make so many connections that way. But before lockdown lifted, as I was embarking on the writing, a couple of new sources appeared. In 2020, Gauguin’s most important written manuscript resurfaced. He called it ‘Avant et aprés’ (Before and After). Two hundred handwritten pages, copiously illustrated, covering his thoughts on God, Life, Art, everything. The manuscript had been known about but lost for a century following his death. Suddenly it reappeared, offered to the British Government in lieu of death duties. Then, in 2021, the catalogue raisonnée was completed. This is like the Bible of an artist’s work, giving you all the information on all the known works. I also discovered a great-granddaughter with a marvellous treasure trove of family papers, many written in Danish and Norwegian. Norwegian is my mother tongue so, as it happened, I was privileged over previous biographers in being able to read both languages.

Which female non-fiction author would you say has impacted your work the most?

When I was at school, I came across the letters of Lady Mary Wortley Montague (1689 – 1762). Being a girl, she was denied learning but ‘stole’ a broad education by hiding in her father’s library, particularly delighting in teaching herself Latin. When her husband was Ambassador to the Ottoman Empire, she accessed female-only spaces, the hammam and the zenana, to learn about women’s lives. She witnessed smallpox inoculation which she introduced to England amid much harrumphing from the medical profession, leading to the eradication of smallpox and the development of vaccines. Admired by Alexander Pope, Voltaire, and other great contemporaries, she wrote poems, travelogues and (anonymously) a book entitled Woman is not Inferior to Man. As a schoolgirl reading her letters, I realised that the only limitations are the ones you set yourself; she gave me courage to shoot for the stars.

What is the best piece of writing advice you have ever received?

I can do no better than go back to George Orwell in Why I Write: ‘Desire to see things as they are, to find out true facts and to store them up for the use of posterity’

Is there a non-fiction book you recommend all the time? If so, what is it and why do you recommend it?

The Pike by Lucy Hughes-Hallett. A page-turning, immensely amusing biography of a repellant human being. Not many writers could pull this off.

What are you currently reading?

I’m reading an advance copy of Hidden Portraits, The Untold Story of Six Women Who Loved Picasso by Sue Roe. I’m reviewing the book for New Statesman magazine. Though there are a zillion books on Picasso, this is the first one on his wives and mistresses. All were unconventional and independently talented women. All inspired new directions in Picasso’s art. He treated them abominably: two committed suicide. It is wonderful to have their stories revealed at last, and their important legacies acknowledged and honoured.