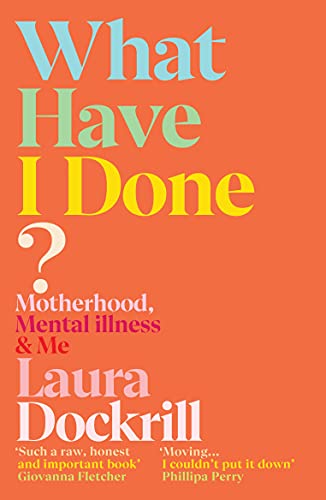

Written by Laura Dockrill

Dreaming and creating fictional worlds has been something I’ve done before I could even hold a pen. It’s how I understand life and live in the world; from my parents breaking up to Geri leaving the Spice Girls, writing has been the way I process. Writing is my full-time job. I rely on my imagination, it’s always been my landing pad, my roots and ground, my touchstone, my sanctuary, my safe space.

Until it wasn’t. Until my mind became the most unbearable, unsafe place on earth.

In 2018, following the traumatic birth of my son, I was hit with the debilitating mental illness, Postpartum Psychosis – don’t worry, I’d never heard of it either until it tried to kill me. The symptoms include anxiety, depression, paranoia, insomnia, delusions and is considered a medical emergency. I found myself waking up on my first Mother’s Day – you really couldn’t write it – in a psychiatric ward separated from my newborn, not knowing how or why I got there, other than ‘it was all in my head.’ I was stalked by shame; blamed myself for my ‘failed’ labour; tortured by guilt; and here I was having a ‘break’ because of an ‘invisible’ ‘invented’ illness, pouring my un-useable, useless breastmilk down the sink whilst my hungry 3-week-old cried out for me at home. Couldn’t I just snap out of it? Cheer up? Be grateful. Couldn’t I be ‘stronger’? Get on with it like everyone else? Be the ‘happiest’ I’d ever been, like the movies said I would be? Had I conjured it up? My brain had betrayed me.

I wrote in hospital like my life depended on it. Mostly desperate attempts of clinging to the steep cliff faces of reality. Any bolts to harness down this abstract, unhinged state for just a granule of time. Proof. Lists. Evidence for the sad case files in my head. Clues. Nurses’ names I didn’t trust. Medication. Apologies. Letters to my baby. Questions to challenge my exhausted partner with at the daily suspicious interrogations I made him endure when he came to visit. Any pearl of wisdom my memory could latch onto during agonising group therapy when I wasn’t ruminating in hell.

Questions to ask my appointed psychiatrist: ‘Is this my fault? Are they going to take my baby away?’ No, he’d reassure, of course not. But he’d know my brain would rewrite the whole conversation anyway. I would hide the notes – but where? Rip up the paper? But I didn’t trust the staff. Eat the paper? Then they’d take the paper away. So instead, I waited for the words to pull me out of the fire. This all sounds like I was going about like a frenzied FBI agent – maybe because I was – like the writing didn’t help, but it definitely did. Without it, I don’t know if I’d be writing this today. I needed that place to process, to anchor. To hack through my jungled mind. Towards the end of my stay at the hospital, I managed to string together a poem (below) – poetry being my first love – I found comfort and buried myself in the familiar: hold on, Laura, you’re going to be ok. For the first time I believed it.

When I was discharged there was a clear Before and After. I’d woken from a night terror. Only I was an unconscious zombie, causing carnage, possibly irreparable damage; upsetting the people I loved the very most. If only I had been in hibernation, like a dozing dormouse – curled up; harmless. No, I had to face it all, return to my life after the shipwreck. It was time to see what remained of my tiny island and rebuild. I already knew writing again was impossible. My brain was not trustworthy. It was a small sacrifice to stay well and care for my son. To ‘go there’ seemed selfish. My only writing dedicated to the necessary, self-taught ABC of CBT; re-writing the unhealthy trenches in my neuropathways until they were overgrown, then carving out fresh healthy roads I could shuffle down. But I found very quickly that what happened was tumbling out; I was like an animal with a wounded paw and the words, like blood, seemed to drip onto the page. Until writing felt like wrapping bandages; I was healing. I began to accept. To shake the guilt and shame and, finally, find recovery; It wasn’t my fault. I did nothing wrong.

I wrote hard and fast, on my phone, mostly because I had a sleeping newborn on my chest and the phone made the writing more casual, like telling a friend. I wrote over 250k words in this way (I mean who would want to read that? Nobody.) Each chapter a message in a bottle. Taking ownership made me feel empowered. I was returning home. Along with mediation, therapy, precious time, the brilliant books of others that ‘lived to tell the tale’ and, of course, bonding with my little boy. Believe me, I know it sounds cheesy, cliché and saccharine but it’s true, writing saved my life. I was my own knight in shining armour.

Sharing lived experiences brings empathy, compassion, kindness, wisdom – all enemies of shame. It’s not the Trauma Olympics; nobody knows all the answers to life, nobody knows the secret of how to do it, but we can help each other. Talking dials down the fear that made you feel so alone, that triggered off the feelings you’ve been trying to avoid. Truth liberates, hope shines a light in the dark. We can look in with courage rather than hiding. Hold close rather than avoiding. Knowledge is power. I wish someone had told me about this illness because I would have known it was possible to survive it. And then sur-THRIVE.

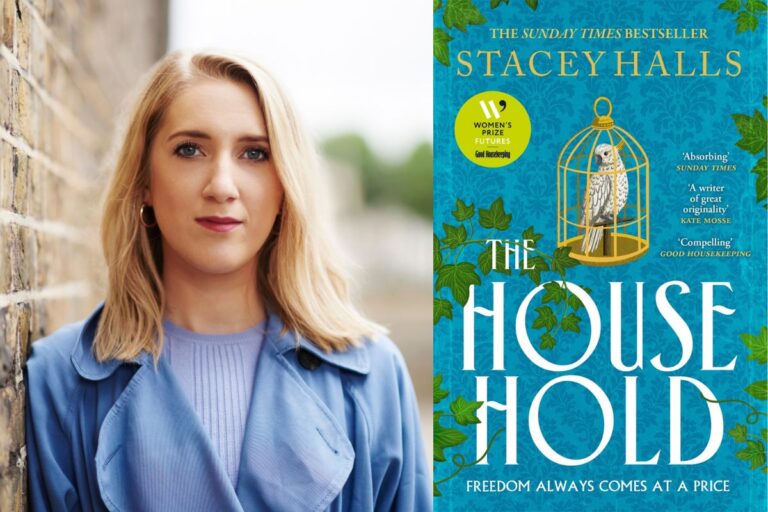

Recently, my memoir What Have I Done? was discussed in Julia Martins’ My Body, My Book Club – an online book club focusing on feminism and bodily autonomy. I joined the session for a Q&A. I mentioned how privileged I felt to even be able to share my story; writing from the vantage point of a healthy, white, middle-class woman with access to (mostly) exceptional healthcare in comparison to many parts of the world; that if there was ever a time to suffer, 2018 is not the worst year to experience a severe postnatal mental illness.

Once upon a time, in history, I might have been locked in an ‘asylum’ for life, called a ‘witch.’ I thought of Jane Eyre’s woman in the attic. Sylvia Plath. But more than that, Julia bought to my attention the very act of writing having such a strong hand in my recovery, Julia said, I was thinking about Silas Weir Mitchell’s ‘rest cure’, which was very popular in the late 19th century for ‘treating’ hysteria – which often included what we would today call postpartum depression and psychosis. He ‘treated’ lots of incredible writers and artists by forbidding them access to paper/ink and books, such as Jane Addams, Edith Wharton, Winifred Howells, and– most famously – Charlotte Perkins Gillman.

Charlotte Perkins Gillman, the author of the chilling short story The Yellow Wallpaper – tracking a woman who is prescribed bed rest. Alone with only her thoughts, without her expression, her autonomy, her paper and ink, she ends up unravelling by the very cure to remedy her. Writing is not the only thing, but this pencil and paper cheap skill is at the end of our fingertips. It’s not about perfection but capturing a feeling. This pen is a sword. A lifejacket. A whistle to blow. A hand to hold. A compass. A torch. We have to keep writing. We have to pollinate the air with our experiences. If not for any other reason than a tribute to yourself, that you are alive, that you made it.

Laura Dockrill is an author, illustrator, script-writer and performance poet from South London. A true polymath, her writing spans children’s, YA and adult, including the acclaimed memoir, What Have I Done?: Motherhood, Mental Illness & Me, and her debut novel, I Love You, I Love You, I Love You, which comes out in 2024. A voracious reader, Laura has judged many literary prizes, including the BBC National Short Story Prize, Blue Peter Book Prize and the BAFTA Children’s Prize.