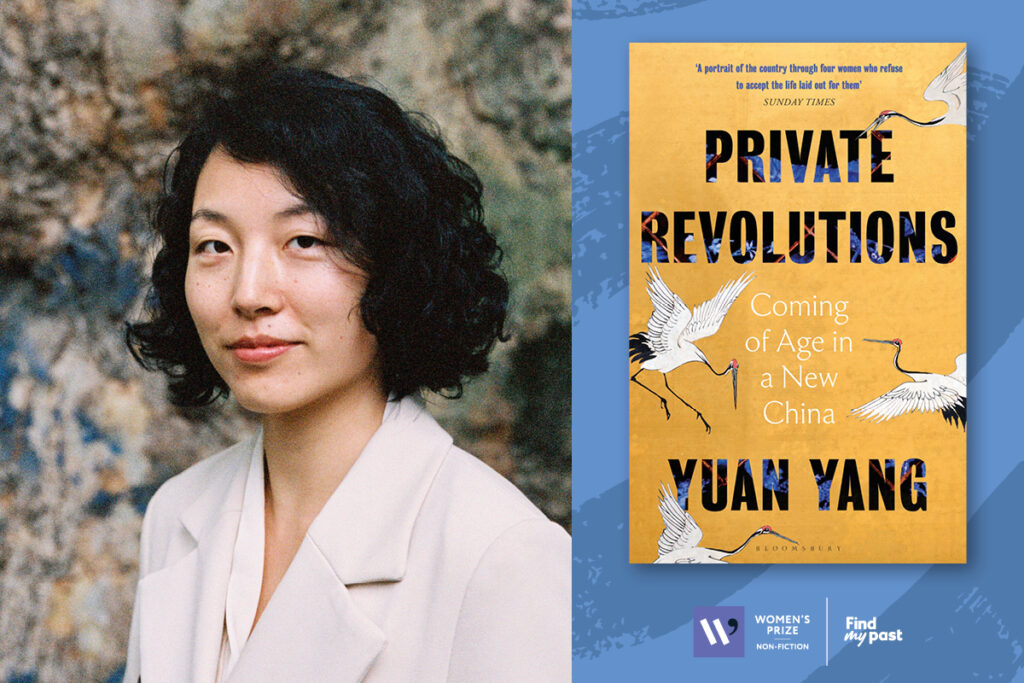

Private Revolutions: Coming of Age in a New China by Yuan Yang is a sweeping yet intimate portrait of modern China told through the lives of four ordinary women, each striving for a better future in an unequal society.

Longlisted for the 2025 Women’s Prize for Non-Fiction, judge Dr Leah Broad says: ‘This is a powerful and intimate portrait of life in a rapidly changing modern China, told through the stories of four young women. It shines a light on the struggles and dreams of individuals that go unheard at a time of unprecedented change.’

To find out more about the book we spoke to Yuan about her writing, research and current reads.

How would you describe your book to a new reader?

Private Revolutions tells the coming-of-age stories of four millennial women who were born during China’s capitalist reforms in 1990, as I was. Together, their lives tell the story of the way China’s economy and society have been ripped apart and reconfigured over the last three decades, as China transformed from a closed, planned economy to an globalised market economy.

I was born in China in 1990, a year after the Tiananmen Square massacre of students and protestors, and my parents moved to the UK a few years after that when I was still very little. The four women in my book were born across four different sections of Chinese society – from an extremely poor and remote mountain village, to a middle-class apartment block in a big city.

These women face common challenges to women around the world: how to make ends meet, how to find and maintain love, how to care for a kid while also working. But their challenges are set in a context that the world had never seen before: in modern China, a rapidly growing and now rapidly slowing superpower, where parents worry about the cooling of social mobility, and the young generation worries about whether things will improve for them as much as it did for their parents.

Did you have any revelation moments when writing your book? When the narrative and your objectives all fell into place?

When I was describing the book I was working on over lunch with a group of female friends in Beijing, Siyue – who at the time was merely a friend of friend, someone I knew through our social circles but did not know well – immediately labelled the social phenomenon I was trying to pinpoint. ‘It’s the fear of falling off the ladder’ Siyue said. I felt this analogy was perfect for describing the precipitous and fragile rise of Chinese middle-class families up the long ladder of wealth, at a time when income inequality is its highest in Chinese history. It captures not only the aspiration to climb higher, but the fear underpinning the aspiration. Siyue later became one of the central characters in the book.

What is the one thing you’d like a reader to take away from reading your book?

The one thing I’d like readers to take away is empathy with the central characters in the book, from completely different backgrounds – class, race, nationality – to them. When I was spending time with the women in this book, I often wondered what my life would’ve been like if I’d been born in a slightly different place or time. I hope this book makes my readers think about that too: how many small accidents of chance have made us who we are — and the common struggles they face with women on the other side of the world from us.

How did you go about researching your book? What resources did you find the most helpful?

My book emerged from six years of reporting for the Financial Times in Beijing, including one year in which I was given book leave to focus on writing (thank you editors!). I travelled for interviews across China, covering major cities as well as remote mountain villages – which were difficult to access because of the political concerns that local government officials hold about foreigners, particularly journalists. I found most helpful speaking to academics abroad about politically sensitive topics I was covering, particularly those relating to social mobility and labour activism, to get a sense-check on my approaches without endangering my interviewees. This network of overseas activists and academics was invaluable for supporting me along my path.

Which female non-fiction author would you say has impacted your work the most?

Leslie Chang.

What is the best piece of writing advice you have ever received?

My mentor at the Financial Times, Robin Kwong (the former Taiwan correspondent), told me you can only really control the inputs, not the impact, of journalistic work. You never know which interviewee, which reporting trip, which story idea is going to become the biggest headline one day. Rather than spend time worrying about the impact and the accolades, you should set yourself goals about the input: the number of stories you pitch, the number of people you meet, the number of words you write in a morning.

Is there a non-fiction book you recommend all the time? If so, what is it and why do you recommend it?

Vivian Gornick’s Fierce Attachments, an autobiographical book which describes the writer’s own coming-of-age in a Jewish tenement in New York City in the 1960s. I admire the psychological precision with which Gornick captures her life, including her early years. She draws out the emotional significance of vignettes from her early childhood memory, making sense of what to most of us can be a jumble of moments from our childhood. She is also unsparing, yet kind, when describing the shades of insanity in her intimate relationships with her mother and her neighbour, two critical female role models in the book.

What are you currently reading?

The Other Significant Others by Rhaina Cohen.