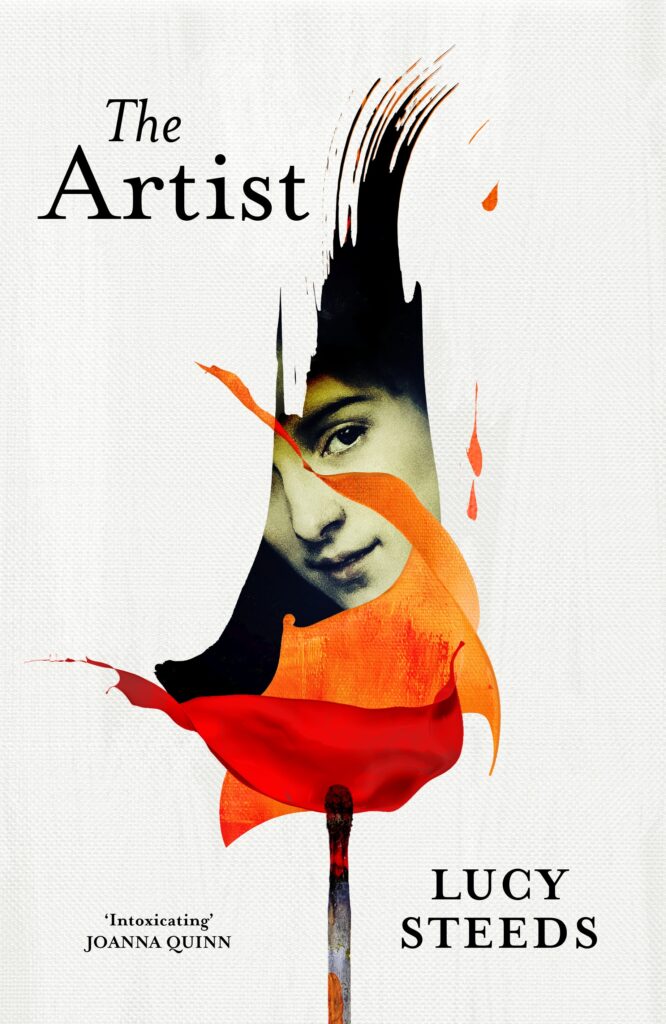

Lucy Steeds’ The Artist tells the story of a domineering artist and his niece’s subversive independence in the shadows of the First World War.

Longlisted for the 2025 Women’s Prize for Fiction, judge Deborah Joseph says: ‘I loved every word of this book. Set during the First World War in Provence it’s about a journalist who goes to interview a reclusive and eminent artist. The writing is beautiful and the description of the art is totally immersive. I was there in the artist’s studio, I could smell the paints, feel the fabrics and sense the light in the room.’

To find out more about the book we spoke to Lucy about her inspirations, writing process and favourite books.

How would you describe your book to a new reader?

The Artist is about three people stuck in a house together over the summer of 1920: Joseph, an aspiring writer, Tata, a painter, and Ettie, his sharp-eyed niece. Joseph believes he’s been invited to the remote, crumbling house to write an article about Tata, but when he arrives he discovers a very different arrangement altogether. Over the sweltering months that follow, the characters circle each other, stripping away one another’s secrets, until they collide. It’s a sneaky, sultry mystery full of art, desire, and deception. It’s about how we create art and how we consume it.

What was the idea that sparked your novel?

There was a very small sentence in a very large book about art history which sparked the idea for the twist in the novel, so I won’t say more about that here. But in general I was thinking about ‘art monsters’: these tyrannical figures who act despicably to the people around them but create great art. I found that I wasn’t so interested in the argument of ‘think of all the art we’ve gained from these monsters’, but in ‘think of all the art we’ve lost’. I wanted to peer underneath these enormous figures and see who was hidden in their shadows. I started looking at paintings and asking myself, ‘What am I not seeing?’

Which part of the book did you write first? Was there a moment that clicked a lot of things in place or where you felt the strands of the book started to come together?

The first thing I wrote was the first line: ‘A stranger comes to town.’ That opening scene remained unchanged through the various drafts, though I later went back and added a Prologue. The moment The Artist really gained momentum was when I realised I had to tell the story from two different perspectives. The novel alternates between Joseph and Ettie’s points of view, and this unlocked the story for me, because suddenly I had a third element: the gap between what each of them sees. There’s something lurking in that gap. One of the novel’s epigraphs is a quotation from John Berger: ‘We only see what we look at. To look is an act of choice.’ I wanted to find a way of expressing this idea in a novel.

Which part of the book was the most fun to write? Which was the most challenging?

Ettie was a deliriously fun character to inhabit. She’s secretive and reveals herself slowly to Joseph and to the reader; you have to gain her trust. Choosing which parts of her to show and when was immensely fun. The most challenging part was finding a way to depict paintings in words. Joseph’s anguish in the novel is how to transform a painting into writing, and this was my anguish too. What do we lose in that translation? What can we gain? I also made up all the paintings in the book so I didn’t have any actual visual aids for this. It was lots of holding fictional images in my head and trying to conjure the precise words to describe them, to the point of headache.

What is the best piece of writing advice you have ever received?

‘Don’t be afraid to entertain the reader.’ My creative writing tutor Peter Benson said this to me after I expounded, at length and with great intensity, about all the important themes I wanted to explore in my novel. After listening to my very serious ideas about art and life he looked at me thoughtfully and said, ‘…but don’t be afraid to have fun.’

Which female author would you say has impacted your work the most?

There are so many! But to pick one from the multitude: a writer who really emboldened me in terms of form was Eleanor Catton. Reading The Luminaries cracked my head wide open in terms of how inventive and how ruthlessly intelligent you could be with the structure of a novel. I love any writer who makes me want to work harder, and Eleanor Catton pushed me to find a way of writing The Artist so that the story’s form reinforced its meaning. The Artist is about what we see and what we don’t, so I wanted to ask: how can you hide something in plain sight in a novel? How can you make the reader feel like they’ve been looking at the wrong thing the whole time? The Artist flits between Joseph and Ettie’s perspectives, and as they loop around each other it becomes clear that what’s important is the distance between them. The novel is about closing that distance.

What is your favourite book from the Women’s Prize library and why?

I am going to be greedy and ask to have Fingersmith by Sarah Waters as a starter, The Goldfinch by Donna Tartt as a main course, and Piranesi by Susanna Clarke for dessert. A banquet of vibrant words and outrageously bold and clever stories. If I had to make a feast out of just one book, though, it would be Wolf Hall by Hilary Mantel. Her writing feels alive: writhing and seething and somehow both full-bodied and also numinous. Her sentences are always the ones to aspire to.

Could you reveal a secret about your creative process?

When I was trying to find an interesting way of writing about art, I used to go to museums and just sit in front of a single painting for an hour. I let the image fill my vision, and then I connected pen to page and just wrote, not looking back at what I had written, not editing, and not correcting as I went. It produced some of the most surprising ways of writing about art I’d come up with. I honed in on the texture of the paint. The movement of the brushstrokes. The oily gloss of the colours. The secret was to enter a painting through the senses, rather than analysing it with my brain. Art in The Artist is never an intellectual pursuit; it’s an emotional one.