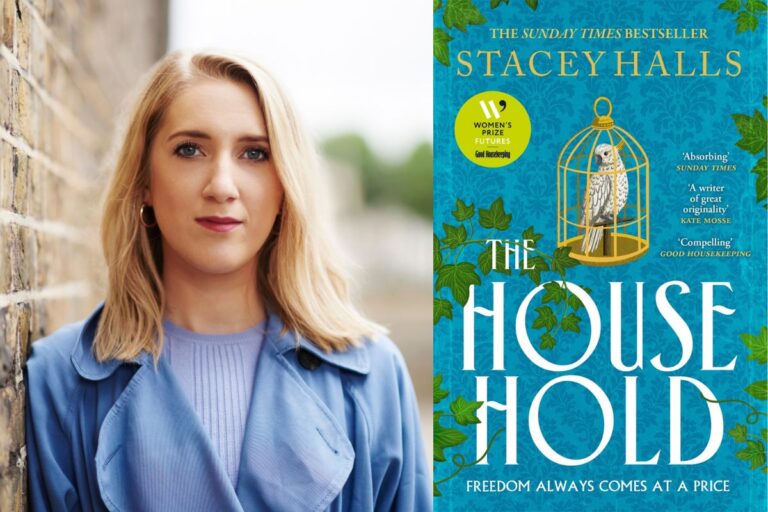

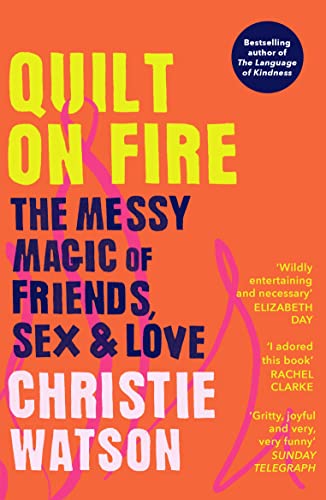

In town with the paperback publication of her new glittering memoir, Quilt on Fire: The Messy Magic of Friends, Sex & Love, Costa award-winning novelist and memoirist Christie Watson shares an insight into the ‘dangerous’ process of writing a memoir and what storytelling, in all its forms, can teach us about ourselves and others.

I was born into storytelling. My mother, a nursery-nurse at the time she became pregnant, balanced books on her expanding belly and read them to me through her skin: The Very Hungry Caterpillar, Peter Pan, Harry the Dirty Dog. When I was three months old, she was pregnant again, and my dad took over while she puked her way through nine months of hyperemesis gravida. Instead of reading, he’d push me in my Maclaren buggy to the roughest pub in Stevenage and, whisky in hand, tell me tales of pirates and cowboys and gangsters. He’d gather a crowd of leathery drunks, who apparently let me lick the foam from their pints, as they listened, wide-eyed. I was weaned on stale beer foam. He told me years later that some of those mates couldn’t read at all, a fact astonishing to me in my privilege.

My brother was born as I turned one, as big as I was small. We were nicknamed Irish Twins and given a boob each while my mum whispered stories to the tops of our heads. One of my earliest memories is from when I was around three or four years old, and at my mum’s nursery. I was sitting cross-legged next to my best friend Daniel during carpet time, both of us listening to mum at the front as she read from a picture book about Chicken Licken, who panics and shouts The Sky Is Falling! creating chaos, until he is told, the sky is not falling. It’s just an acorn that landed on your head. It remains one of my favourite books, because, as with most writers I suspect, I hard relate to Chicken Licken. And that little best friend Daniel from when I was three or four years old, is now my partner. Every now and then he will hold my arms still, and look at me and smile, before reminding me: ‘The sky is not falling in, love.’

That’s what stories do. They show us ourselves. Whether it’s a children’s book about a chicken, or a memoir about a universal experience with which we identify: grief, love, loss. The best stories, however we tell them, are those with characters who stay with us long after we’ve turned the last page. Character is everything in any genre.

Christie Watson

I began as a novelist, and became so immersed in my fictional world that I dreamed in it. Novel-writing is all consuming, in my experience, in a way that non-fiction is not. When writing novels, I may appear to be in a room with others, I may even appear to be listening fully, and engaging in life. But half of me is elsewhere for the duration of a first draft. I’m an extrovert, but still, during the first year of a novel there is no other company I would rather be in than that of my imaginary friends. It’s quite magical (if anti-social), and it does not mix well with parenting. I have just written my third novel, Moral Injuries, which will be out next year, and am in a mild state of grieving. These three women I have made up, and written intensively over a gazillion drafts, have become very real to me. And now they are gone, into the ether, vanished in smoke. Of course, I realise this all sounds a bit eccentric. I was on a panel once with a psychiatrist who was listing psychosis symptoms, and I realised that novelists exhibit quite a few. Do you hear voices that aren’t there? Tick! See people or objects that don’t exist? Tick! Tick! Tick! Novelists, and those experiencing psychosis, walk an imaginative tightrope.

Writing memoir is dangerous in a different way. Quilt on Fire: The Messy Magic of Friends, Sex and Love – my third memoir – is just out in paperback, and while the writing wasn’t as all- consuming as a novel, it was challenging and cathartic in equal measures. I had never given much thought to plot, and in early editorial meetings for my first memoir, I heard words like ‘architecture,’ and ‘structure’ repeated endlessly. The craft needed to formulate a cohesive account of a life into a universal truth is the work of memoir, and it is hard work. I treat writing memoir like any blue-collar writer would: I’m at my desk grappling from 9-6 most days, often including weekends, and outside those times everything I consume in media, film, television, or books, is in some way related to the project I’m working on at that time. The most difficult part of memoir is not the ‘architecture’, the working out of the spine of the narrative that holds it all together, but the crippling anxiety it can offer during the process. If you write a novel and people hate it, well, each unto their own. If you write memoir and people hate it, then surely, they hate you? Silencing this voice is the memoirist’s best literary weapon. I have written six books now, three novels, three memoir, and discovered differences in focus and creative process and narrative priorities between the forms. But there is one rule that somehow keeps me going. I always try to remember this, particularly at the first draft phase: the sky is not falling. It’s just an acorn.