Last year, our 2022 Chair of Judges Mary Ann Sieghart discovered through research for her book, The Authority Gap, that most men don’t read books by women. We ran a campaign to highlight essential reading for men – seminal novels written by women – asking friends of the Women’s Prize Trust to recommend their favourite reads, then asking you to vote for the top ten.

We want to continue to encourage men to read more novels by women, so we asked some familiar faces to read and review the six spectacular books on this year’s shortlist. Read on to for thoughts and insights on the 2023 shortlist from scientist and writer, Adam Rutherford; author and journalist Clive Myrie; musician and Bastille frontman Dan Smith; comedian Russell Kane; acclaimed author Lee Child; and Mayor of London Sadiq Khan.

Adam Rutherford on Pod by Laline Paull

‘The drama of a coming-of-age tale, wrapped up in a classic flawed hero’s call to adventure. Warring tribes, plucky protagonists, disabilities, a collapsing ecosystem brought on by powerful cruel invaders, on top of politics, personalities, sex, partying, feuds, dancing, sex (there’s enough to warrant listing it twice), battles, carnage and destruction. This exhilarating story has more than a touch of Game of Thrones, and would make a cinematic epic redolent of Avatar. The major difference in the novel Pod by Laline Paull is that the carefully drawn characters are not the House Lannister or the blue alien Na’vi. They are dolphins.

Spinner dolphins, more specifically, who engage with roughhousing bottlenoses, and wise whales and other beasts of the seas, though they are not really beasts at all, but a very believable cast. Much to the delight of this evolutionary biologist – I have written extensively about the often-unpalatable behaviours of cetaceans – Paull does not shy away from the reality of the lives of sea creatures. They are hierarchical, violent and sexually aggressive, and about as far from Flipper as Paddington is from a Grisly Bear. And ultimately, in this thrilling adventure of marine mammals, we see our own story.’ – Adam Rutherford, scientist and writer

Clive Myrie on Black Butterflies by Priscilla Morris

‘Libraries are inanimate objects, holding inanimate objects. Their threat isn’t physical. Yet they are so often victims of war, attacked, bombed, and shelled. Why? I saw it during the Croatian War of Independence in the early 1990s, the Dubrovnik Inter-University Centre library, destroyed by missiles. In Mali in 2013, Islamist insurgents retreating from Timbuktu, torched a library containing thousands of priceless historic manuscripts. Most recently in Ukraine, the national Library Association says 25 university libraries have been severely damaged or destroyed and 47 public libraries have been levelled.

It’s in this context that I read Priscilla Morris’ powerful and beautifully written book. Set in Sarajevo in 1992, the city- ancient yet multicultural and modern, is terrorised and besieged by Serbian nationalist forces for nearly 4 years. The national library is attacked early on, with the fires raining down the black ashes of burning books, over the city. Zora an artist needs her work to survive, her studio in the library is destroyed, but her will to create beauty amid the rubble from the debris of war is undimmed, and a moving testament to the power of art and human resilience. Libraries are repositories of memory and culture, that’s why they’re so often attacked. Priscilla Morris writes hauntingly about the library as a metaphor, for a culture others want to destroy.’ – Clive Myrie, BBC Presenter

Dan Smith on The Marriage Portrait by Maggie O’Farrell

‘I loved The Marriage Portrait and was totally immersed in this imagined history of Lucrezia, a young Duchess in 16th Century Italy. I’ve been reading this on tour busses and in windowless backstage rooms, and have really loved being transported by O’Farrell into the vividly realised world of Renaissance Italian court, in all of its stifling, claustrophobic pomp.

There’s a wonderful eye for detail – the architecture, food, fashions and smells of the courts and countryside we find ourselves in – but at it’s heart is our heroine Lucrezia, who is smart, creative and independent of mind. She bristles against the constraints of her life, and the expectations thrust on her as – not only a girl in that time and place – but as the youngest daughter of The Grand Duke and Duchess, and then as young bride of a strange Duke.

We see this bizarre Renaissance world through her warm, questioning and thoughtful eyes. The absurdities and injustices of the time are picked over by this 15 year old girl who has had adulthood, sex, child-bearing expectations and fame thrust upon her, and still she breathes humanity into these often shockingly cold and inhuman situations.

O’Farrell makes us contemplate the timeless notion of objectivity in portraiture. On one level, the novel charts the painting of a grandly commissioned portrait of this new bride – one commissioned by her husband in an aim to show her as an wealthy and glorified Duchess. But as a point of contrast, O’Farrell is keen to explore Lucrezia inner life – giving us a more raw and honest portrait of “little Lucrezia” and the marriage she’s forced into.

At it’s core The Marriage Portrait is also an unfurling tragedy – told fantastically across two parallel time periods – and a tension brews throughout the novel as we desperately wait to discover the fate of Lucrezia – who’s life is being threatened by her sometimes charming, sometimes terrifying new husband.

I found the book to be a moving and gripping insight into girlhood and womanhood, and the tragedy of individualism in a world that has specific expectations.’ – Dan Smith, singer songwriter (and founder of Bastille)

Russell Kane on Trespasses by Louise Kennedy

‘Now and again you pick up a novel and such is its spell, it melds with the flesh on your hand for a few days – and it stays there until it is absorbed. Trespasses is such a novel. Yes, on the surface, a story of forbidden love (on so many levels) between a younger catholic woman Cushla, and an older Protestant Barrister Michael; yet, apart from the very sinews of the human heart which pulse on every page – it’s the atmospheric detail that sucker punches you. You can taste the smoky air, feel the sticky carpet. Sense the resentments in the corner of every pub and every room. You feel the piercing gazes of the older people watching and judging. If this makes it sound like a brilliantly written love story with evocative history and detail…. Then I have sold it short.

Yes it has top-tier literary writing that will slake someone like me (a lover of everything from Zadie Smith to Iris Murdoch) – sure – it has that, but it has something that is too often bloody-well missing. Story. A terrifying plot set in recent history – and taking place both inside and outside the characters. This is how the book the builds its energy…. I won’t reveal where it goes… but all the elements come together with devastating effect. If you are not shaking when you turn the last page, then you are the one with the troubles….’ – Russell Kane, comedian

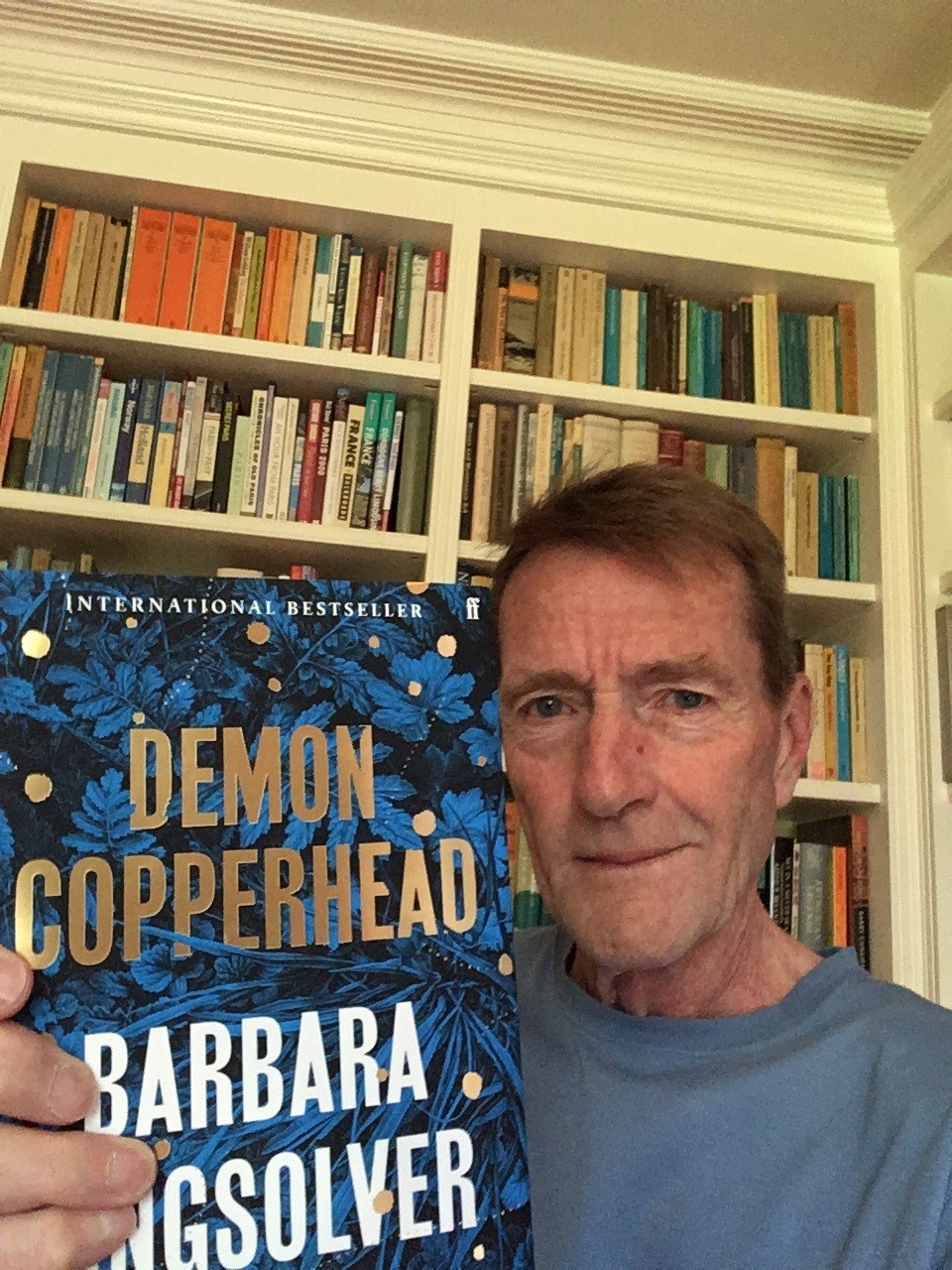

Lee Child on Demon Copperhead by Barbara Kingsolver

‘A lifetime of reading taught me that a great author will be a person of restless intelligence, nagging curiosity, passionate conviction – and, of course, enough sheer writing talent to put on the page what needs to be there. Barbara Kingsolver is exactly that author. Her life has been one of exploration, investigation, advocacy and concern. Her literary ability was demonstrated beyond a reasonable doubt by The Poisonwood Bible, a complex and emotional family story told by five interwoven first-person narrative strands, with no demarcation between them other than the utterly distinctive clarity of the separate voices. A tour de force indeed.

Now, in Demon Copperhead, Kingsolver gives us a bildungsroman using Charles Dickens’ David Copperfield as … what exactly? A foundation? A template? She herself, in an author’s note, calls her new novel an adaptation, to her own place and time. OK, but my reading suggests she was actually using the earlier work as a question. We deploy the adjective “Dickensian” to mean something grotesquely awful, long ago. We expect things to have gotten better since then. Kingsolver asks: have they really?

And the answer is no, not really. Young Demon has problems just as bad as young David ever did. His story is just as heartbreaking, and just as almost-inspiring, told with Kingsolver’s absolute mastery of voice, which modulates subtly as Demon ages. In summary, I can’t do better than quote Kingsolver herself, again from her author’s note: “For the kids who wake up hungry in those dark places every day, who’ve lost their families to poverty and pain pills, whose caseworkers keep losing their files, who feel invisible, or wish they were: this book is for you.” Advocacy, conviction, concern – and another tour de force.’ – Lee Child, bestselling novelist

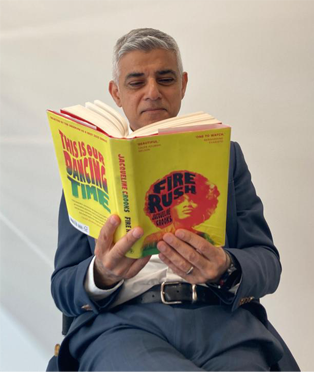

Sadiq Khan on Fire Rush by Jacqueline Crooks

‘A remarkable debut. Crook’s debut novel transports you on an atmospheric, immersive journey from the dub reggae revolution of 70’s London to Bristol to Jamaica and beyond. Each section, whilst distinct, flows beautifully – portrayed through the unique lens of protagonist Yamaye in an often male-dominated world. A whole host of characters, from friends Asase and Rumer, to the quietly compelling Moose, are portrayed in a style rich with insight. Fire Rush is a story of love, of freedom, of honesty and hope. Evocative, powerful and at times painful, this atmospheric book is a must-read.’ – Sadiq Khan, Mayor of London