From the Women’s Prize Archives.

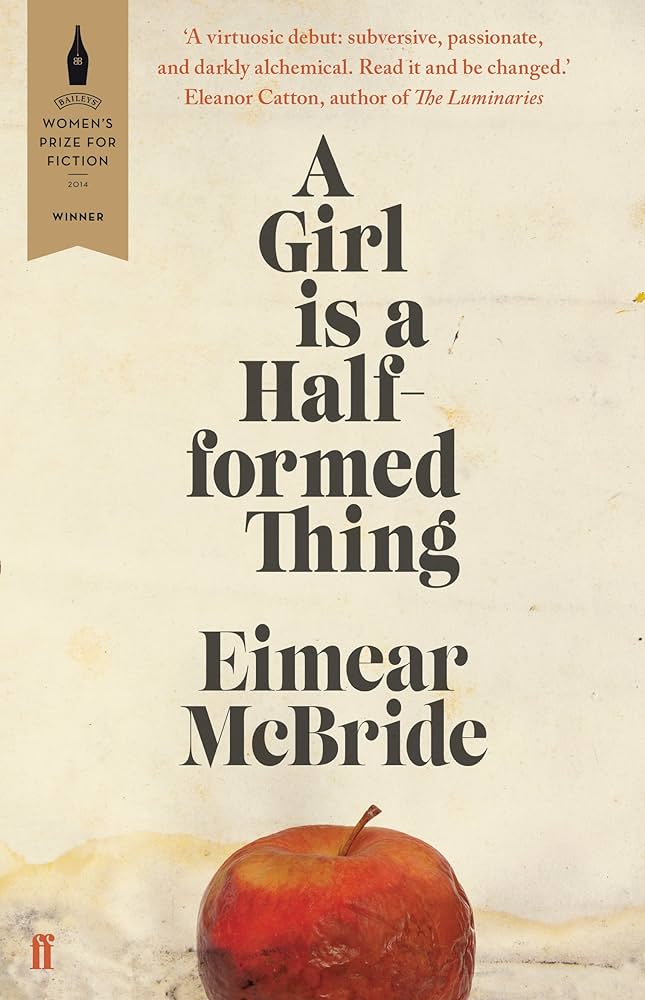

We caught up with Eimear McBride on the inspiration behind A Girl is a Half-Formed Thing, the complexity of growing up as a woman and how her professional acting background has informed her fiction.

Where did the initial idea for A Girl is a Half-Formed Thing come from?

I didn’t sit down with any notion of what eventually became Girl in my head. It was really a matter of accidentally hitting on that initial image of the child in the womb, and the language surrounding it, which started it. It interested me in a writeable way so I followed it and, from there, it was a matter of chasing the imagery and her voice to its logical conclusion

The idea of being ‘fully-formed,’ of becoming a woman, is central to the novel – was this an important thing for you to write about?

Yes, I think the struggle to become a woman is a much ignored process. Girls tend to be left to their own devices when it comes to the problems of incipient womanhood, or that was certainly the case for my generation. Preserving your virginity was really the only commandment and everything else was either polite of impolite behaviour. To speak about the complexity of many basic problems around sexuality, abuse, separating out from the family and the desire for independence -albeit in an extreme setting- seemed a subject worth tackling.

Did you always want to write the novel in a Joycean, stream-of-consciousness style?

Well, Joycean was never the aim, although he was the inspiration behind trying to uncover a different mode of literary communication. Stream-of-consciousness was interesting to me but also seemed to have been taken as far as it could go. So instead it was my jumping-off point. I wanted to take the great communicability of that style and make it work harder, go deeper, express more.

The novel is very critical of religious fervour in Ireland – is this an issue you feel strongly about?

I think it was an issue I didn’t realise I felt so strongly about until I began to write about it. I very quickly uncovered a well of previously unacknowledged fury within myself though about the appalling treatment of women and girls by the religious -institutional and lay, alike. I still can’t quite believe the audacity of their inhumanity, their vindictive petty wickednesses and the smug, self-assured disregard for even the most basic decency or kindness.

You’re a trained actor – does this experience inform your fiction in any way?

Yes, hugely. If I had gone to university and studied English or Creative Writing I would be a completely different writer. Drama Centre -where I trained- taught me everything I know about taking risks, about not taking the easy route out of artistic problems and dealing with the fear of difficult consequences. It also taught me not to be feel too reverential about language, to make it physical but, most importantly, it taught me how to look at a person and try to understand them without making a moral judgment.