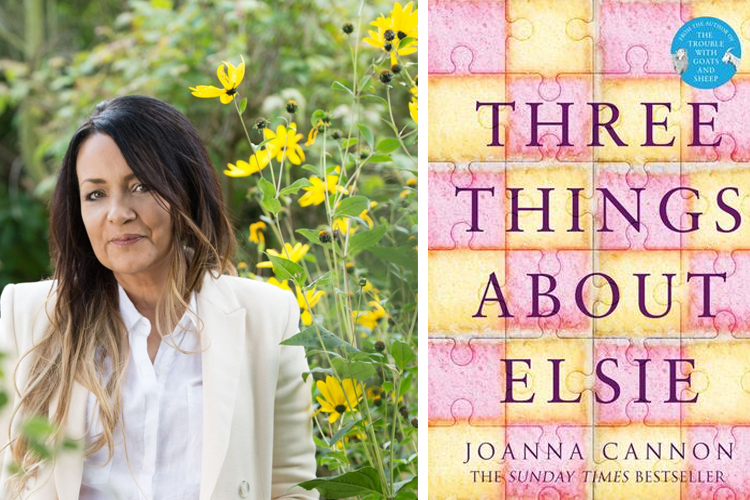

From the Women’s Prize Archives.

The brilliant Joanna Cannon has been longlisted for the 2018 Women’s Prize for Fiction for Three Things about Elsie. Read on to find out how Joanna’s background as a psychiatrist affected her writing and why finding the extra-ordinary in the ordinary is now sparking her third novel.

Did you find writing your second novel more challenging, given the success of your debut?

I think they were both challenging, but for very different reasons. Writing my debut was a challenge, because I’d never previously written anything. I was a reader, not a writer. I set myself a personal challenge to finish a novel, without any notion of being published, and the whole process became an adventure. With Three Things About Elsie, I was writing with the weight of expectation hanging over me, and I had to learn, very quickly, to ignore that expectation, and return to writing purely for the joy of writing. The biggest challenge for an author, I think, is that it’s very much like standing on a giant stage and saying ‘this is how I feel about the world, does anyone else feel the same way?’ which is an incredibly scary thing to do.

What research did you do to enable you to inhabit an 84 year-old woman so convincingly?

Working on the medical wards gave me a huge insight into how it must feel to grow old. There is a very high percentage of elderly patients within medicine, and it was a privilege to be involved in their care and have the opportunity to get to know them. Whilst I would never write about real people, hearing their stories and understanding the challenges they face was definitely inspirational when it came to writing about Florence and Elsie. As a medic, my greatest downfall was being too absorbent, and I found it very difficult to distance myself from the suffering and grief I witnessed each day. However, as is very often the case, your biggest downfall is often also your greatest strength, and that sensitivity was very useful for writing, because it meant I found it a little easier to walk in someone else’s shoes.

Does your background as a psychiatrist affect the way you approach your characters?

Definitely. There are huge parallels between psychiatry and writing, and in both, everything rests on a narrative. Someone with mental health problems – through absolutely no fault of their own – can very often be the ultimate unreliable narrator, and as a doctor, you need to search for other clues to help put a picture together. Someone’s appearance, behaviour, the words they choose to give you and how those words are delivered, all become part of the riddle you need to solve, and when you take a psychiatric history, you are very much playing the same role as a reader trying to make sense of a story. Working in mental health services, you very quickly realise that narrative is everything. We are all made of stories.

In many ways, the book is about memories and how we revisit the past. Was this an important theme for you to write about?

I think it was one of the first things I considered when I began Three Things About Elsie. Whenever I write, I always ask myself ‘why am I doing this, what am I trying to say – what is the point of it?’ Loss of memory and sense of self was something I’d thought about many times when I worked with people living with dementia. Everything we do – our reactions, behaviours, flaws, strengths – all stem from the past, from what we’ve learned, so there is always the question of whether, when we lose our memory, do we lose who we used to be?

Can you tell us what are working on next?

At the moment, I am deep into writing book three. As with my first two novels, I know exactly how it begins and exactly how it ends, and the rest of the story is happening organically. I always need to hear a clear voice, though, and the voice for my third novel is, again, someone on the edges of society, looking in. I am a huge fan of unlikely heroes, of hearing a story that might not otherwise be heard, and growing up on a diet of Alan Bennett, I will always be fascinated by how extra-ordinary the ordinary can be.