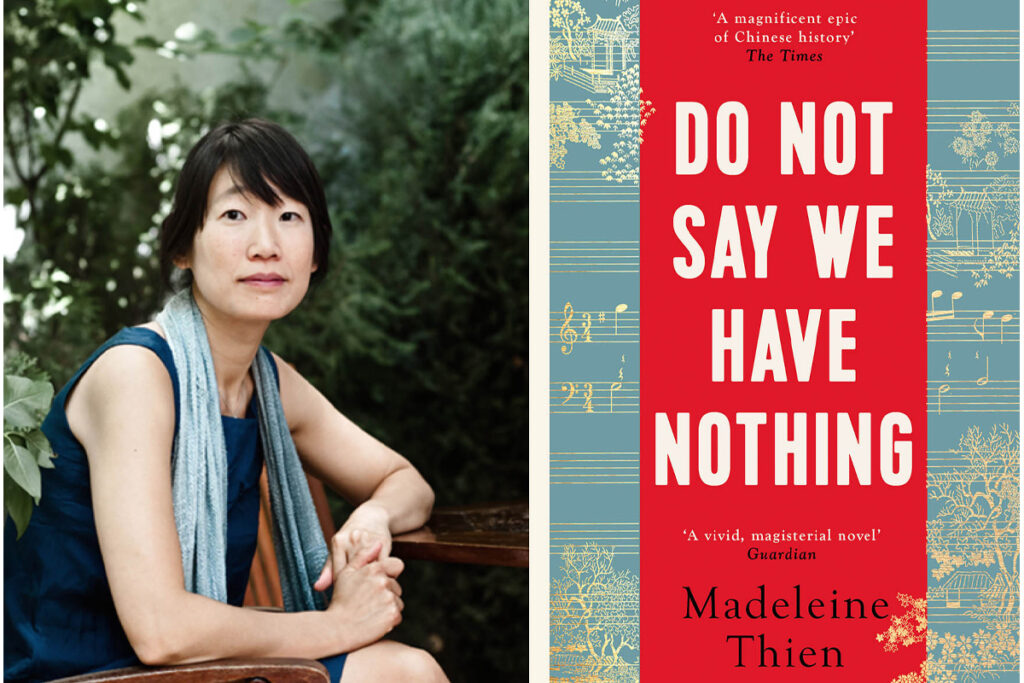

From the Women’s Prize Archives.

The brilliant Madeleine Thein has been longlisted for the 2017 Baileys Women’s Prize for Fiction for Do Not Say We Have Nothing. We caught up with Madeleine to talk translating music into the written word, the failure of language and literary heroines.

Do Not Say We Have Nothing is a novel of huge scope, spanning the Chinese Cultural Revolution – what made you want to tackle this enormous subject?

I wanted the novel to unfold in a very specific time frame, the lifetime of an individual – the birth, life and death of a composer we know as Sparrow. He’s born at a historical crossroads: the fall of China’s Republican government and the birth of Communist China. History pulls his life apart, he’s at the mercy of so many forces, and yet he’s also free. In one sense, his life is taken from him; in another, it’s the only life he has and he must live it.

Sparrow is as much his unwritten music as his finished music (an echo of China’s unofficial history, the unwritten, lost or censored), and he is created as much by silence as by sound.

The story is also full of music; how did you go about translating the sensation of music into the written word?

It’s a beautiful question and such a difficult one to answer. The music is part of the way the characters live and think, it is continuous and part of the cadence of their lives, even when we don’t hear it. It’s like the music is always there in another room, and sometimes we (the readers, the listeners) become alert to it. We turn our heads, close our eyes and it surrounds us.

In many ways, this novel is also about the failure of language, of being stripped of your voice. Could you tell us more about why this was an important thing for you to write about?

Yes, I’ve been troubled by language for a long time. How we choose our words, how language can build meaning but also conceal or demean it.

The characters are living in a moment when political language – what we might think of as Party speak or ideological language – is mandatory. You cannot escape it, and you must learn how to use it. During China’s political campaigns, speaking the revolutionary language fluently demonstrated that you had the correct thinking. And vice versa: to choose the wrong language would be to reveal yourself as an enemy of the people. And this is all complicated by fact that revolutionary language has a profound purpose, to teach us how to think outside the closed systems we live within.

During the Cultural Revolution, permissible language became the same as permissible thinking. Sometimes, if one made a mistake, it would simply be corrected. Other times, it could cost a person their jobs or their freedom; and other times, their lives.

If one is not careful, this public language has the power to erode, and potentially replace, one’s private self. For Kai, it slowly becomes the only way in which he knows how to exist, to think and to love.

Who are your literary heroines?

Alice Munro, Tsitsi Dangarembga, Shirley Hazzard, Yiyun Li, Dionne Brand, Hannah Arendt and so many more.

Could you tell us what you are working on at the moment?

A short story about the arrival, in the 1970s, of a Cambodian refugee family to the town of Goderich, to an area known as Alice Munro country. And I’m working on a new novel, which is still changing and shifting every time I try to see it clearly. I’m very excited about it.