What pulls you into a story and captures your imagination? The perfect plot, the eye-catching cover, the killer hook? For many it’s that opening line, one of the first opportunities to grab the attention of the reader and reel them in. In celebration of launching our Discoveries programme for 2025, we’ve partnered with Doubleday, to hear from some of their authors about what their favourite first line of a book is and what makes them so special…

I was not sorry when my brother died.

Chosen by Paula Hawkins, author of The Blue Hour

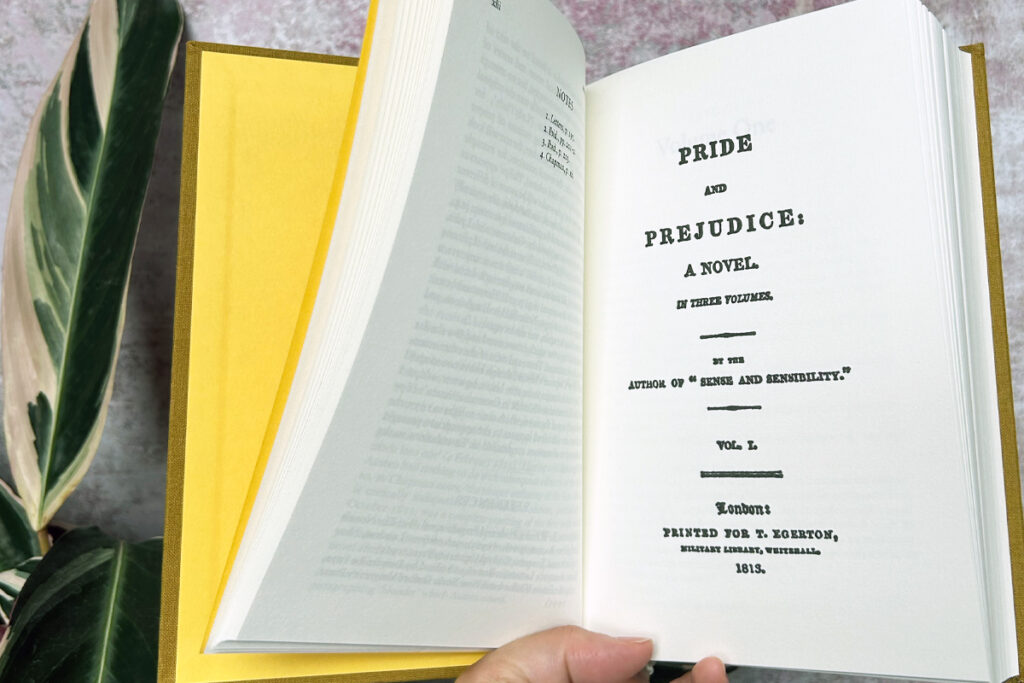

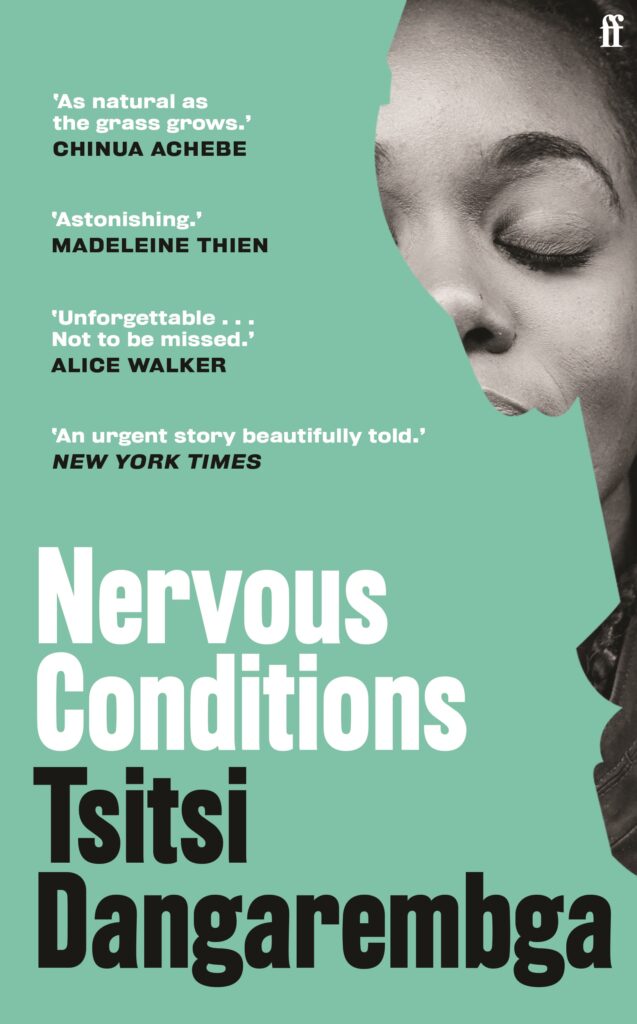

Short, not sweet. The first line of Tsitsi Dangarembga’s groundbreaking debut novel, Nervous Conditions, introduces us in disquieting and memorable fashion to her singular young narrator, Tambudzai Sigauke. Just eight words, and yet they contain multitudes, hinting at so much of what is to come in this extraordinary coming-of-age novel set in 1960s Rhodesia. In those eight words we glimpse not just Tambu’s resentment of her older brother, but her yearning to take his place. In his death she spies an opportunity to get the education she believes will enable her to lift herself and her family out of poverty. Above all, though, in that first line we see so much of Tambu herself: unapologetic, unsentimental, clear-eyed and determined.

Published in the UK in 1988, Nervous Conditions was the first novel by a black Zimbabwean woman ever to be published in English. It was awarded a Commonwealth Writers Prize in 1989, and in 2018 was named by the BBC as one of the one hundred books that have shaped the world. Everyone should read it.

It is a truth universally acknowledged, that a single man in possession of a good fortune, must be in want of a wife.

Chosen by Rachel Joyce, author of The Homemade God

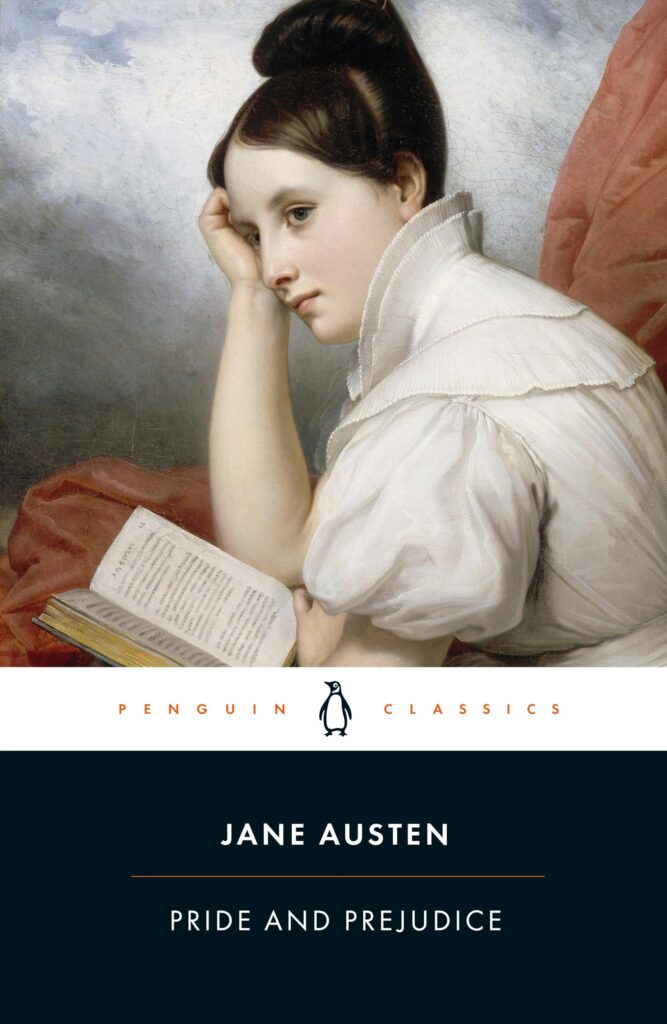

I have this theory that you should be able to understand the world of a book from the very first word. If the jacket is the front door to your novel, then the opening line is the person on the other side who invites you in. Are they agreeable? Half in shadow? Mysterious? You get the gist. The opening line holds the identity of the book and, in one way or another, suggests what you will find inside. It sets out the tone – you are going to be able to laugh in this book, you will be on the edge of your seat. It’s the casting of a spell.

And Jane Austen casts her spell perfectly. This will be a story about marriage, but it will also turn that idea on its head. It sets up the world of the novel, its tone – a little playful, even arch. (Who says this is the truth?) It also sets up the confines of the ‘universal’ world and allows room for the question of what the ‘wife’ might ‘want’.

I go over the opening line of my own books many times. People laugh when I tell them that, but it’s true. It’s also true that it never comes to me when I first begin writing: I can only really know the opening line once I know the last one.

And never forget that other brilliant opening line, ‘Once upon a time …’

Ever since my mom died, I cry in H Mart.

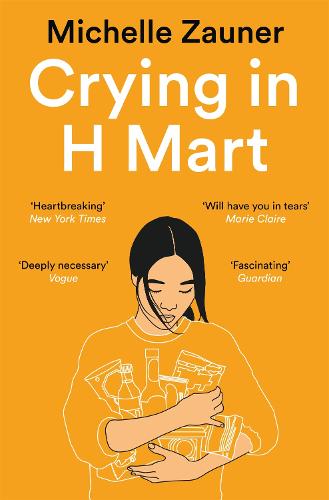

Chosen by Nicola Dinan, author of Disappoint Me

Michelle Zauner opens her memoir with a simple yet deeply layered sentence, far exceeding its few words in meaning. Grief doesn’t care if you’re on a busy train, driving your car, or standing in an aisle of H Mart, the largest Korean supermarket chain in the United States. The line reminds me so much of one of life’s cruellest ironies: the rituals we use to feel closer to what we’ve lost often remind us of the fact of that loss most painfully (and what stronger ritual is there than the drawing together of food, memory and culture?). Crying in H Mart is a beautiful and powerfully intimate book, and as someone who has lost a parent, it touched me deeply.

‘And the material doesn’t stain,’ the salesgirl says.

Chosen by Sophie Haydock, author of Madame Matisse

This is the subtle but telling opening line to a radical novella, The Driver’s Seat, by the Scottish novelist Muriel Spark, published in 1970. This statement inspires intrigue from the reader. As the narrator quickly reveals, Lise is on an existential errand to get herself killed. This early indication of the fate of the protagonist leaves us to focus on how and why the inevitable will unfold. As readers, we are gripped. As a writer, this is a technique I hugely admire. The Driver’s Seat was ahead of its time – subverting the suspense format, where the outcome is often withheld. Instead, the main character – a seemingly erratic woman in her mid-thirties – has uncanny agency over her own fate. Lise is not a victim. She is given a voice. The Driver’s Seat becomes a meditation on control, free will and self-destruction. And from the first line to the last, we are willing passengers, along for the ride.

The snow in the mountains was melting and Bunny had been dead for several weeks before we came to understand the gravity of our situation.

Chosen by Lottie Hazell, author of Piglet

A survey of my bookshelves confirmed that, while there are many excellent first sentences, there aren’t many that are truly exceptional. When researching, I found opening gambits tended to do one or maybe two of the following: establish voice or tone, introduce character, locate the reader in a point of space or time, or set expectations of the type of story to follow.

Donna Tartt, in the first sentence of The Secret History, of course manages all of the above. This one line teases the unfurling of a murder mystery, establishes a darkly comedic tone, outlines setting, and introduces character. An economic sentence, indeed! I need to confess, given The Secret History’s degree of popularity, that I can’t count myself as one of the foremost leaders of the fandom. Proof, if we needed it, not to get too hung up on the sentence level? But when I think about the launch this line gives us, it perhaps explains why this novel has such an enduring power. It is, as many have observed before me, a mystery in which the reader is not encouraged to ask ‘who’ but instead ‘why’. I find the boldness of this first line an inspiration: when I sit down to write, I am always trying to channel the efficiency and skill of a writer like Donna Tartt.

If I have learned anything in this long life of mine, it is this: In love we find out who we want to be; in war we find out who we are.

Chosen by Josie Ferguson, author of The Silence in Between

A novel’s first line is a promise to the reader of what is to come. Kristin Hannah’s opening line of The Nightingale promises a story about love and war, heartbreak and death, characters who will discover that they are stronger and more compassionate than they imagined, but others who will discover that they are capable of cruel, unspeakable things. War reveals the darkest sides of humanity but also the lightest. From this sentence, we don’t yet know how love and war will shape the protagonist, but personally I couldn’t sleep until I found out. Not only does Hannah’s opening tell us what kind of book we’re about to read, it also makes us ask ourselves: Who am I in love? Who would I be in war?

Where does a mistake begin? Lately I’ve found this simple question difficult. Impossible, actually. A mistake has roots in both time and space – a person’s reasoning and her whereabouts. Somewhere in the intersection of those two dimensions is the precisely bounded mistake – in nautical terms, its coordinates.

Chosen by Catherine Newman, author of Sandwich

Sea Wife is an absolutely glorious novel about a marriage and an ocean voyage – both going catastrophically awry – and I just love the way Amity Gaige opens the book with such heavy philosophical musing on the nature of error. It’s a little like the overture of a musical, only grim: you can feel the whole book in these opening notes. You can sense something of the shape it’s going to take. And you don’t know how it’s going to go badly, but you know that it is. I’m more of a ‘She had leftover sausages for lunch that day’ first-line writer. But boy do I admire this kind of meticulous craftsmanship.

124 was spiteful.

Chosen by Carmella Lowkis, author of Spitting Gold

The opening of Toni Morrison’s Beloved is everything that I want in a first line. With just three words, it immediately hooks us into the story and its themes. We start with a mystery: what or who is 124, and why is it spiteful? We’ll soon learn the what (a house), but the why won’t be answered until much later, when we learn the traumatized history of its inhabitants. ‘Spiteful’ is the perfect word choice here, as it implies intention. Whether we interpret this as personification or literal sentience, we understand that there’s a tension here: the house is not just a passive evil; it is actively plotting. By introducing us to the haunted-house setting and its secrets before we learn about any of the characters or context, Morrison sets this up as the focal mystery of Beloved. It’s a first line that hangs satisfyingly over the rest of the book, only really making sense once you’ve reached the narrative’s end.

They were supposed to stay at the beach a week, but neither of them had the heart for it and they decided to come back early.

Chosen by Ericka Waller, author of Goodbye Birdie Greenwing

I could have picked any opening line of Anne Tyler’s. She has this way of starting her stories in the middle, of talking to us as if we are friends. She reels you in so seamlessly. I can see her streets and hear the phone ring in the house with the linoleum floors. I believe everything Tyler’s characters say and feel. There is a card-game scene in The Accidental Tourist that is so perfectly written I often go back to it, just to marvel. The humour. The way she captures sibling relationships. The games we made up aeons ago that will always be ours alone. How she mentions a chair is tucked in, or that someone stops to scratch the cat behind the ears. When I read Anne Tyler, I am there, with her, and not here, with me. I cannot hear the tap leaking or the dog barking. I am in a different country, body, mind, soul.