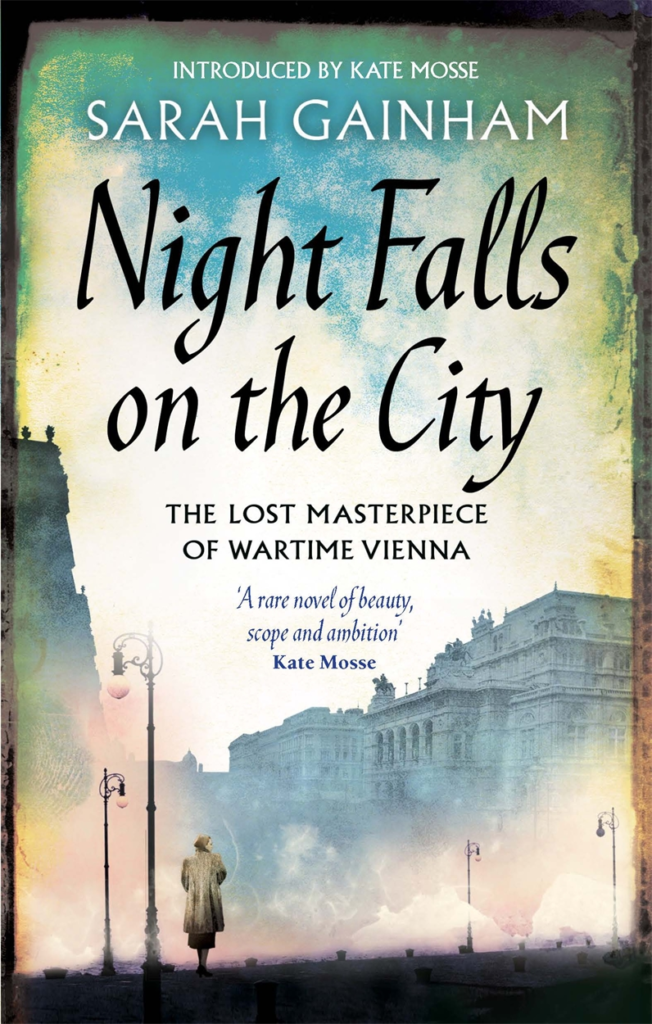

For this feature of Women Writers Revisited we’ve invited the brilliant best-selling author and founder director of the Women’s Prize Kate Mosse to reintroduce us to ingenious British historical fiction writer, Sarah Gainham (1915-1999), perhaps most famous for her 1967 novel Night Falls on the City.

All bar one of Sarah Gainham’s dozen novels were set in central Europe, a region she came to know intimately after the Second World War. Born Rachel Steiner in London (she took her nom de plume from her maternal great-grandmother), she moved to Germany shortly after WWII, then settled in Vienna in 1947 where she remained for the rest of her life. From the mid-fifties to mid-sixties, she was the Central European correspondent for the Spectator, and her first novel, Time Right Deadly (1956) – and the four that followed – are thrillers drawing on her own experiences and knowledge. But it was with her fifth novel, Night Falls on the City – the first in a Trilogy of novels about Vienna – that Gainham found her true voice.

It is one of those rare novels of beauty and scope and ambition that succeeds both in bringing to life a particular moment in history, a particular society, while at the same time rejoicing in the minute details of everyday life, everyday emotions. It opens at the Burgtheater in Vienna in March 1938, on the eve of the Anchluss between Hitler’s Germany and Austria. From the first lines we are plunged into the ancient city on the brink of Occupation. In spite of the rattlings of war, the ‘blunt snouts of tanks’ on the border, this is a world of chandeliers and glittering glass and champagne, a world the protagonists do not yet quite believe will be taken from them. The tone is naive, flecked through with disbelief and arrogance. By the time the novel closes – in May 1945 with the Russians entering Vienna – the guileless spirit of the opening pages has been replaced by one of despair, hopelessness, weariness after seven years of betrayal, occupation, brutality and horror. The consequences of living with tyranny, with fear and the slow death of hope, are clear: ‘the tiny steps, averting of eyes that make a situation possible’.

Gainham is excellent at balancing real history with imagination and, without the effort being apparent, lays bare the background which makes it possible for the Nazis to enter Austria without a shot being fired – the rampant inflation, the terms of the Treaty of Versailles, mass unemployment, poverty, jealousy, an existing peasant class and servant class, the mood of the kind of young men who join the SA and SS with their ‘bellies full of undigested resentment’. She is equally strong in describing the volatile atmosphere of the beer cellars and the mob violence in the poorer districts, the markets and the railway stations and the decimated Jewish quarter as she is in bringing to life the comfortable drawing rooms and country estates of the rich.

Of course, the contemporary reader has the advantage over the characters. We know, as we turn the page and then the next, how real is the threat and what is to come. We have the architecture of the story. There are, if you like, no surprises Gainham can spring on us. Yet it is testament to her great skill that she writes some very harrowing scenes and succeeds in making us feel we are reading such horrors for the first time: the murder of an old Jewish scholar in front of his family and neighbours, the brutalising of a peasant woman in the market, the petty violences inflicted by boys in uniform drunk on power.

Gainham is without judgement – she is a novelist, not an historian – but the question the novel asks is implicit in every scene: how would we act in a similar situation and what might we do to survive? At what cost? The justifications for not engaging, the self-loathing, the thin line between acceptance and resignation, the compromises each is prepared to make: as Julia says, ‘we are all rotten with lying’.

In some ways, Vienna itself is one of the most important and enduring characters: ‘the tempered grey stone, the steely sky and shadowed, blue-white snow’. Gainham’s love for the city, its changing seasons, underpins the sense of loss and waste and destruction at the heart of the novel. Our sympathies are also for the city as it is, little by little, corrupted and compromised and destroyed. Throughout, the beauty of the architecture and art and theatre are there as counterbalances to the seeping ugliness of the Occupation.

When it was first published in 1967, Night Falls on the City was a worldwide bestseller, especially in the United States, where it sat at the top of the New York Times bestseller list for several months. The second and third novels in the Trilogy – A Place in the Country and Private Worlds – followed in 1969 and 1971, but Night Falls on the City is undoubtedly her masterpiece. A courageous, timely novel that deserves to be better know.