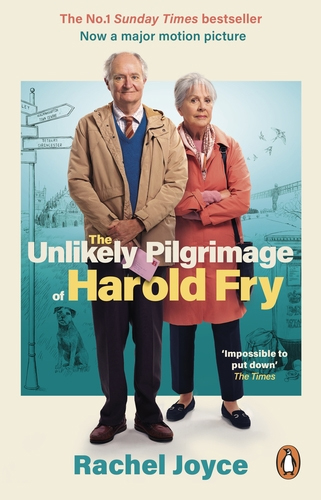

The Unlikely Pilgrimage of Harold Fry by Women’s Prize judge Rachel Joyce was a runaway bestseller. Harold won the hearts of millions of readers around the world and he’s finally made it all the way to the silver screen. We asked Rachel to tell us more about what it was like to adapt the book for the big screen.

When I set out to adapt my book The Unlikely Pilgrimage of Harold Fry into a screenplay, I had two clear rules. I would do it without flashbacks and I would add new material. I ended up with a script with flashbacks and my new material ended up exactly where it deserved to be – on the floor beside my desk. My task was not to embellish the book but to raid it for its key events, and to do it such a way that the film would acquire a life of its own. The most liberating moment was when I realised I had no responsibility to the book, but every responsibility to the story.

So how do you lift a book that is pretty much set in the head of its protagonist into a film that is a series of active visual images? How do you invite the audience into Harold’s world, private as it is, and ensure they are rooting for him from the start? This was why I was so wrong about cutting flashbacks. Flashbacks are little clues into what Harold is thinking. They are not stories in themselves. They are a passing moment, a half-glimpsed image, that causes Harold to do something differently from the way he was doing it before. We don’t even completely understand them. We only know that they are enough to intrigue us; to hint that hidden beneath the narrative, here is someone clearly very troubled by something in the past. In the end, the film fitted together like pieces of a giant jigsaw puzzle. It’s just that I revealed them in snaps and starts, and each one was triggered by the action in the present.

I came to see that my script was like the working manual for the film. A kind of road map. Each scene held a new sign post within a tight structure and I had to make it clear to everyone involved what those sign posts were. It was also my job to suggest landmarks that would help all the other creatives when they came on board to work their magic. Landscape and light became a key feature of the road map. Scenery imposes itself on the narrative and light often reflects Harold’s mood – a horizon hit with bolts of sunlight as he realises Queenie is waiting; a vast storm-tossed landscape with a pewter sky and trees shaking like tentacles in water, as he emotionally loses his way. It was a way of laying a trail for the production team through the story I saw in my mind.

It was the same for the actors. I gave them a kind of road map too. I have always loved dialogue with a lot of space around it because it feels rich and alive with conflict. So I wrote scenes that were as long as those in the book and then I cut and cut and cut. I took slivers from the beginning, the middle and the end. I do not know how to rationally explain this but when you cut something, the ghost of it remains.

Seeing the film come to life was many things – joyful, moving, exhausting, humbling – they changed by the day. I was enormously proud that there were so many women involved – the director, the Director of Photography, the Production Designer, the Costume Designer, Make-up and Hair Designer, the Supervising Location Manager, the Gaffer and Head of Lighting, the Casting Director, Stunt Co-ordinator, Post Production Supervisor, not to mention the female dominant production team. I loved watching the ways these women worked together to enrich and bring to life that roadmap I had given them. Of course when it came to filming, there were things no one – with the best organising skills in the world – could change. Yes, my script said it was a beautiful day but if it was not a beautiful day, you could not stop filming and sitting around waiting for a break in the rain. I have never seen so many soaking wet people as I saw on that set. In this way something happened that not one of us had quite found the words for beforehand: the weather and nature became an essential part of the filming process, in the same way that they had also infiltrated the book. Because maybe what brings a script to life in the end is that last final element. Within its tightly wrought structure, its clear road map, there must still room for the unexpected. For that moment when the rules get broken.