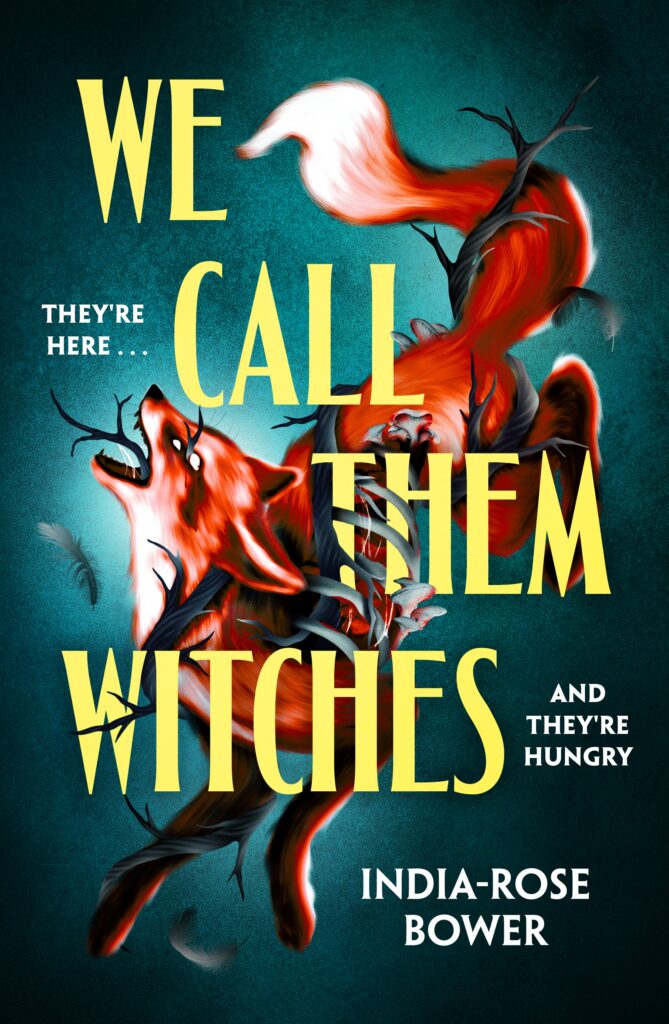

2023 Discoveries longlisted India-Rose Bower has released her debut novel, We Call Them Witches. Described as ‘a fresh take on dystopian horror’, We Call Them Witches is a horror and sapphic romance steeped in pagan folklore that’s set in a apocalyptic world full of sinister creatures. To celebrate publication, we caught up with India-Rose to hear more about her writing process and her thoughts on the rise of eco-horror.

You may have heard the term ‘cli-fi’ being used more and more recently. Short for climate-fiction, it loosely describes literature that focuses on our changing environment – and the ways we’ve changed it. While the term feels fresh, new, this kind of artwork has been around for as long as humans have told stories, and in the world of the macabre, cli-fi turns easily into ‘eco-horror’.

Eco-horror covers more than you might think. War of the Worlds is eco-horror, but so is Jaws or Cocaine Bear. Ranging from deadly weather conditions and dangerous animals, to bio-weapons and global food shortages, eco-horror is, at its heart, a brutal reminder that we are not alone on this planet, and that our actions have consequences.

Horror uses personal anxieties to express social and global fears. In the 60s, the Red Scare produced books like Ira Levin’s Rosemary’s Baby, stories that wondered aloud if we could trust our communities, our neighbours. The 70s saw the emergence of slasher films as a response to America’s sudden proliferation of serial killers, a trend that eventually grew tired and led to the meta-horror of the 90s. Our fears as a society bleed into the arts like rot into wallpaper, growing blooms of terrifying tales that spread inexorably until a new fear takes hold.

The last time eco-horror saw such a rise in popularity was the 50s, with books like Daphne Du Maurier’s The Birds (and the subsequent Hitchcock film). Films about monsters were all the rage, from Godzilla’s rampage to giant, irradiated ants in Them!. Is it any wonder, in a post-war world, that artists felt drawn to explore the terror of nuclear attacks, of giant, unstoppable horrors emerging from the sea to destroy whole cities? Six years of war birthed fears of annihilation, provoked widespread existential dread, and what do humans do when we are afraid of something? We tell stories about it. We dissect it, find ways to experience the fear in safe, controlled environments.

Now, in a world scarred by a global pandemic, where we are told, almost daily, how increasingly irreparable the damage we’ve done is, eco-horror is surely a natural response. As global temperatures tick ever higher and more and more species vanish from the face of the earth, our helplessness can feel overwhelming. Even if you’re doing everything right, recycling, reusing, turning off the tap while you brush your teeth, it can feel like you’re an ant (and not the giant nuclear kind) trying to stop a boulder from crushing your colony.

When I began writing We Call Them Witches, I knew I wanted to design a creature that was impossibly deadly and linked to the earth in a way that was intrinsic to their creation. The witches, grotesque, eldritch beings that take on elements of their immediate vicinity, came from my interest in the effects we have on the world. They aren’t just creatures of roots and moss, of birds’ nests and antlers. They are also throats stuffed with binbags, glass eyes taken from teddy bears, ball gowns and porcelain. They are, in many ways, just a step away from The Beast from 20,000 Fathoms or the giant ants of Them!.

Eco-horror has always been an intrinsic part of the landscape of horror, only now the fears it exposes are startlingly close, terrifyingly real. In our helplessness and our desire for control, for a solution, we turn readily to horror, books and films that show us nature taking revenge, or simply removing us from the top of the food chain. There’s something cathartic in reading the world as it might easily become. And, when we’re done, we can shut the book and put it down, and not forget that it isn’t as fictional as we might like to believe.