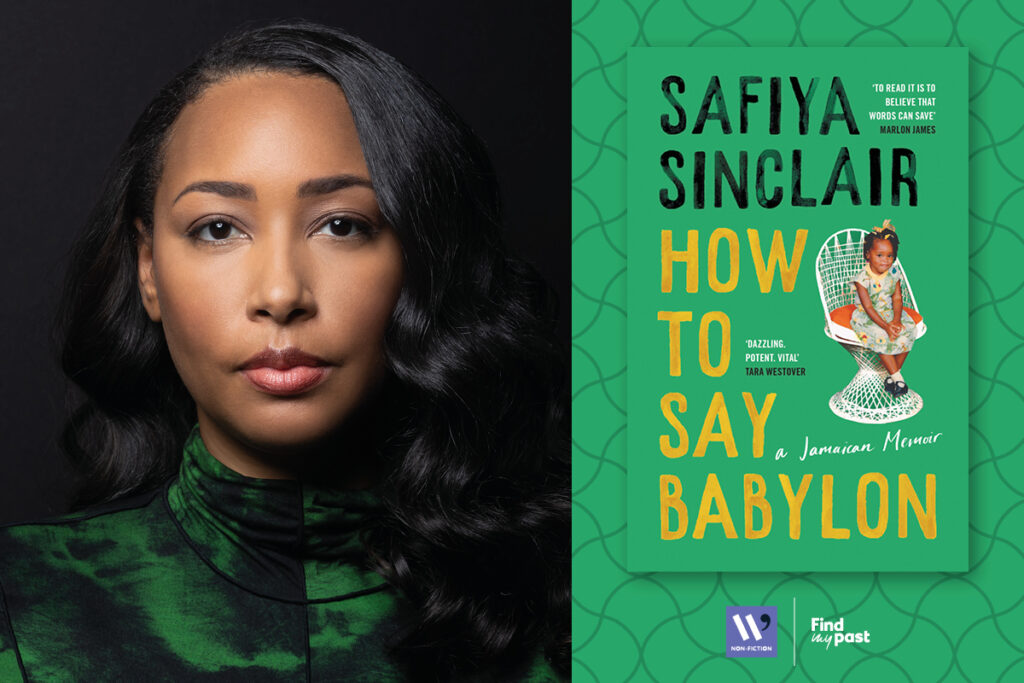

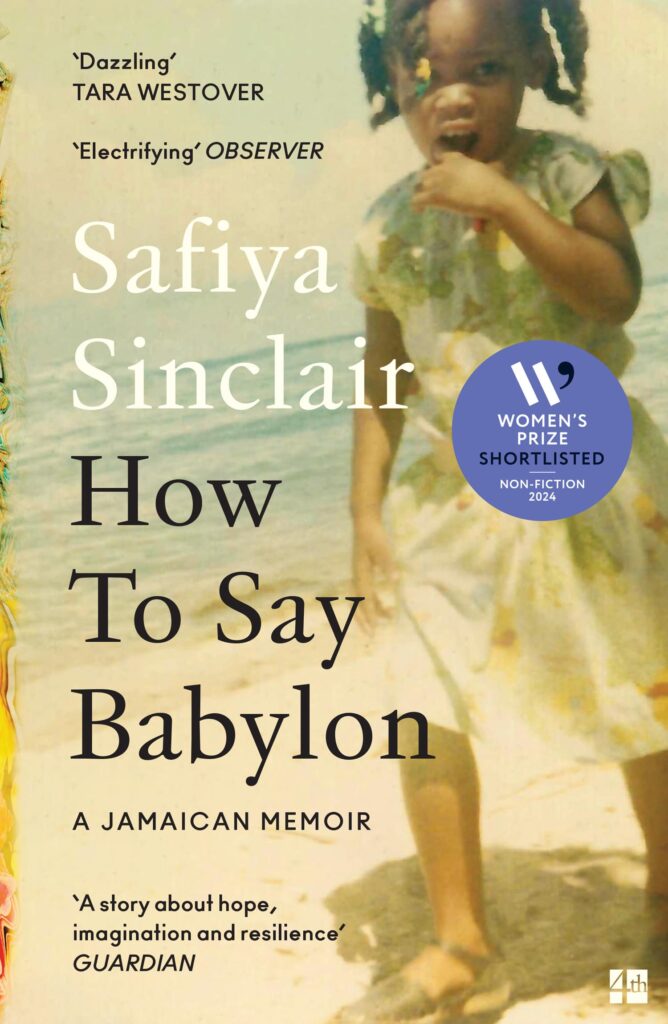

How to Say Babylon: A Jamaican Memoir by Safiya Sinclair is an unforgettable story of a young woman’s determination to live life on her own terms.

Longlisted for the 2024 Womens Prize for Non-Fiction, judge Prof. Nicola Rollock said: ‘A lyrical, evocative, and beautifully written memoir about growing up Rastafari in rural Jamaica.’

To find out more about the book we spoke to Safiya about her writing, research and current reads.

Describe your book in one sentence as if you were telling a friend.

A memoir of my childhood and adolescence growing up in a strict Rastafari household in Jamaica, and how rejecting the rigidity of its patriarchal rules led me to finding my voice as a woman and poet.

Did you have any revelation moments when writing your book? When the narrative and your objectives all fell into place?

When I first began writing this story, I didn’t know how it would end. I felt as though I were writing a ghost story, with empty chambers, and doors I kept permanently closed. It had been years since I’d spoken to my father, and in the beginning, I wrote each word from this place of lack; from a wound. I abandoned the memoir many times. I didn’t want to write this book from a wound. It was hard to ignore how much our unresolved fracturing loomed over the pages, and I began to think that the book was too haunted by these many traumas to feel whole. In 2018, six years after I abandoned the idea of writing this memoir, I went to give my first poetry reading in Jamaica and invited my father to come hear me read for the first time. There I read a poem I had written for him and decided to speak to him eye to eye for perhaps the first time in our life, asking him to hear me. When I left the stage, he embraced me and whispered in my ear “I’m listening, and I hear you.” This was the first time I felt released from the wound. Finally, I could begin writing the book, because now I knew how it would end. Not with severance or rejection or revenge, but with forgiveness. Until this moment, I had never considered myself a forgiving person. I had always been taught to see the world the way my father saw it—through fire and brimstone, control and power. What would I do now that I was the one with the power to tell our story? It dawned on me then, with some surprise, as I struggled with the book’s structure, that I had to see the world the way my mother saw it. With potential. With possibility. With the hope of building a future that might alchemize the hurt of our past into something better, something beautiful. Her story begins in the place I will always return to, the sea, and its boundless expanse, the young girl looking into the frayed face of her future and, like all the women who came before her, choosing to save the girl who comes next.

What is the one thing you’d like a reader to take away from reading your book?

As Sonia Sanchez once said, “I write to tell the truth… therefore I write to offer a Black woman’s view of the world.” I wrote How to Say Babylon to give readers a keener understanding of Caribbean womanhood, to offer a personal portrait into what a young Rasta girl’s life is like, her pains and fears and dreams and desires. I also wrote this story to give insight into Jamaican culture and Rastafari history beyond the tourist brochure. But primarily, I wrote this book as a bridge of possibilities into the future, in hope that any woman throttled under religious patriarchy sees the strength of herself here, that she too can speak herself into power. That every word, in some sense, will always begin with the word and breath and thought of “She.” So she who comes next will survive.

Which other female non-fiction writers inspire you and why? Any particular title?

I am continually inspired and awed by Audre Lorde’s non-fiction, particularly the way she blends biography, myth, and history—what she calls “biomythography”—in her essay collection, Sister Outsider, and her memoir, Zami: A New Spelling of My Name. Lorde uses biomythography as a frame through which Black women must express themselves with a double or triple-consciousness in the world, which informed the way I structured my memoir, as folklore and history and poetry layered on top of each other, told in wefts of chronology, the crests and waves of a Caribbean life, rather than a straight line. I also admire Donna Haraway’s A Cyborg Manifesto, where she introduces the idea that a woman of color is often as dehumanized in Western society as a “cyborg identity…, synthesized from fusions of outsider identities.” Both Lorde and Haraway provided me with the tools needed to contextualize my own portrait of Black girlhood, interweaving the voices of the women in my family to explore how in the female body, as in the tropics, nothing grows politely. I’m also inspired by Maggie Nelson’s The Argonauts and Cathy Park Hong’s Minor Feelings for the keen and intangible ways they each pioneer the intersections of womanhood and “otherness” to creative incisive portraits of women’s lives. And I admire Tara Westover’s Educated for the way she unflinchingly examines the many ways a young girl might be smothered by religious repression but is instead utterly transformed by the potency of literature.

What is the best piece of writing advice you have ever received?

When I first began writing this memoir, I was a graduate student studying poetry in the US. I was estranged from my father and brother, and I felt severed from home in a way I’d never been before. I couldn’t sleep. Each night I was terrorized by the familial violence I had fled in Jamaica. There were times that I felt that writing this book would destroy me entirely. Then my professor and advisor at the time, a poet named Gregory Orr, told me I needed to write my memoir from a “place of safety”: “Remember how I twist Wordsworth’s ’emotion recollected in tranquility’ into a more modern statement: ‘trauma remembered and revisited from a place of safety?’ That place of safety—you may not yet have that,” he told me, and advised me to write this book only when I found that place of safety. It was the most profound writing advice I’ve ever received, and one that saved my life, and saved this book in the process. Without finding that place safety, without seeking the possibility for my own healing, this book would not exist.

What book is currently on your nightstand?

Let Us Descend by Jesmyn Ward

Theophanies by Sarah Ghazal Ali

Ours by Phillip B. Williams

I Know What the Red Clay Looks Like: The Voice and Vision of Black Women Writers by Rebecca Carroll