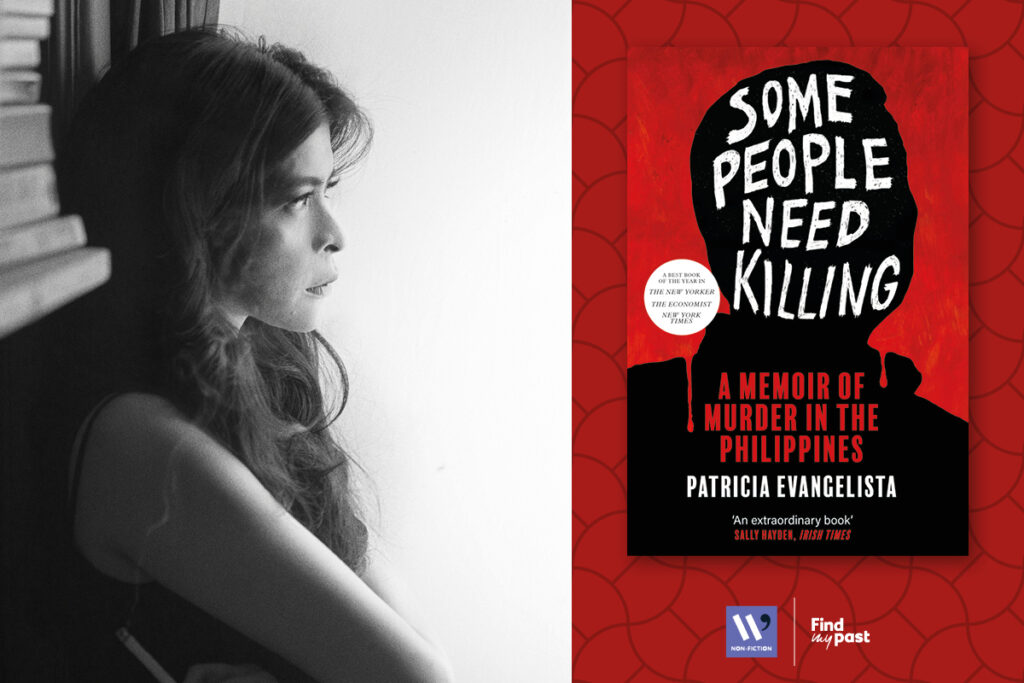

Some People Need Killing: A Memoir of Murder in the Philippines by Patricia Evangelista is a profound act of witness and a tour de force of literary journalism.

Longlisted for the 2024 Women’s Prize for Non-Fiction, judge Professor Suzannah Lipscomb had this to say about the book: ‘This is a magnificent, brave book about the extra-judicial murders in the Philippines under Rodrigo Duterte. It is written in taut, powerful prose. One of the most important books I’ve ever read.’

To find out more about the book we spoke to Patricia about her writing, research and current reads.

Describe your book in one sentence as if you were telling a friend.

Some People Need Killing is an investigation of state-sanctioned terror during the Philippine war on drugs and a cautionary tale of what happens when strongmen rise, and we let them.

Did you have any revelation moments when writing your book? When the narrative and your objectives all fell into place?

One day in 2018, I sat across a man who described himself as a vigilante. He called himself a religious man, a family man, a man who would fight for the future of his children. He had also, by his own admission, murdered two men and was the active participant in the executions of a handful of others.

I asked him how he squared the act of killing with his conscience. “I’m not a bad guy,” he told me. “I’m not all bad. It’s just some people need killing.”

It was, for me, the starkest expression of the psychological accommodation Duterte’s war demanded from his citizens. It became the title of the book I eventually wrote about the execution of the war and the rhetoric that allowed it.

It was, however, only when I was writing the epilogue, less than a year before I published, that I understood how the grammar of that sentence carried the argument through. “Some people need killing” is an active sentence, not passive. The subject is the people. The object is the killing. Killing is not the verb, needing is. The drug addicts needed to die. They had chosen their own deaths. They earned their dying, had it coming, traded the right to live.

That was the revelatory moment for me, when narrative met rhetoric met objective. The language did not allow for accountability. The standard was arbitrary. Some people were addicts, dealers, criminals. The execution of their deaths was a performance of duty. All that was required was the determination of who deserved to live, and that determination was made by the president and applauded down the line. As above, so below.

What is the one thing you’d like a reader to take away from reading your book?

Every war is driven by a story. This is a book about what happens when we don’t challenge the words and the stories we’re told. I hope that at a time when we are being told many stories and we are hearing many words, we take the time to reflect carefully, and recognize we can make a choice.

Which other female non-fiction writers inspire you and why? Any particular title?

I have, as many writers do, read and reread Joan Didion’s collection of nonfiction, We Tell Ourselves Stories in Order to Live, both because of her incisiveness and the delicate rhythm of her writing. I am also inspired by the tremendous empathy Svetlana Alexievitch demonstrates across her reporting in The Unwomanly Face of War: An Oral History of Women in World War II, and Martha Gellhorn’s extraordinary articulation of journalism as personal resistance in The Face of War.

What is the best piece of writing advice you have ever received?

I went to my first and only writing workshop in my early twenties, held along the coastline of Dumaguete in the Philippines. The woman who ran it, the late Edith Tiempo, was an extraordinarily gifted poet and teacher. She was taking apart someone’s poetry when she wrote a single sentence on the white board. “Trim the fat,” she wrote. What she meant was to practice narrative restraint: in language, in dialogue, in storytelling. It has been my guiding principle across more than a decade of journalism.

What book is currently on your nightstand?

I am reading Safiya Sinclair’s How to Say Babylon and rereading Terry Pratchett’s Nation.