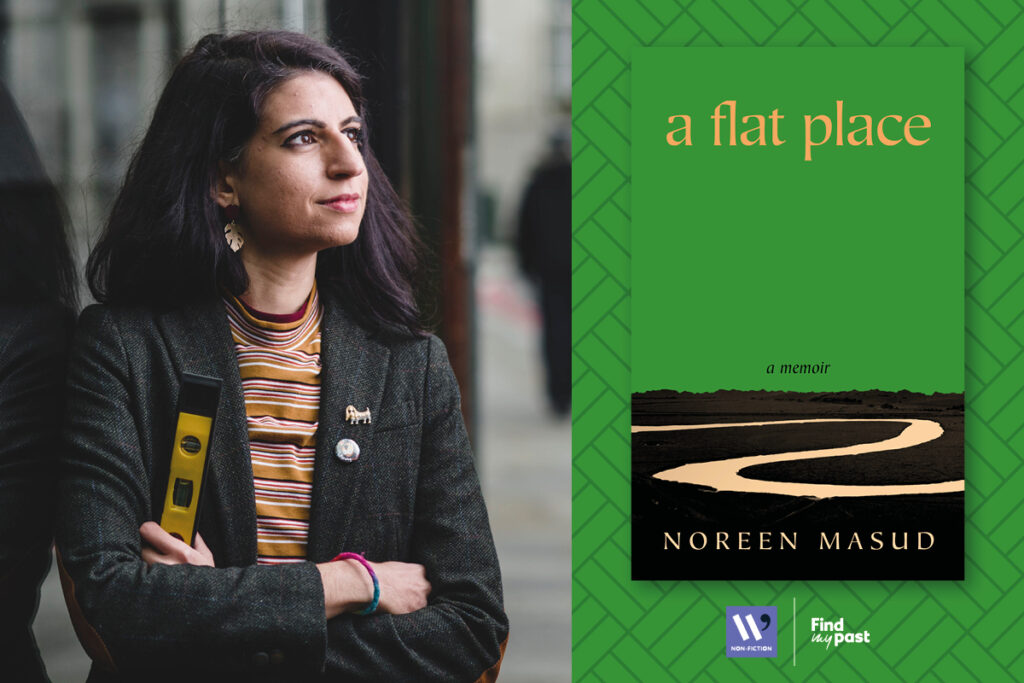

A Flat Place by Noreen Masud is a startlingly strange, vivid and intimate account of a post-traumatic, post-colonial landscape – a seemingly flat and motionless place which is nevertheless defiantly alive.

Longlisted for the 2024 Women’s Prize for Non-Fiction, judge Kamila Shamsie had this to say about the book: ‘I love this for its originality and its intelligence. It is revelatory about both people and places.’

To find out more about the book we spoke to Noreen about her writing, research and current reads.

Describe your book in one sentence as if you were telling a friend.

A Flat Place is a memoir-travelogue about Britain’s beautiful flat landscapes: how they might show us a new way of relating to one another, and a new mode of solidarity in a still-too-colonial world.

Did you have any revelation moments when writing your book? When the narrative and your objectives all fell into place?

A Flat Place began life as a more-or-less straightforward book about flat landscapes. But my agent kept sending back my drafts, saying that he was puzzled: that my responses to landscapes seemed very strange and idiosyncratic, and he couldn’t see the logic behind them. Eventually I wrote him an apologetic note, explaining my therapist’s working assumption that I have complex post-traumatic stress disorder, the result of my childhood years in a frightening and unsafe household; that it filters every aspect of the way I respond to the world, including flat landscapes; and that I feel safest in flat places because of my tendency to dissociate and my fear of other people. And my agent responded, wisely, that this probably ought to be included in the narrative. So it became a book in part about complex trauma: its flatland-like lack of landmarks, its tensions, its resistance to narrative. Once we both understood this, A Flat Place started to work.

What is the one thing you’d like a reader to take away from reading your book?

That lives and priorities we cannot understand – whether migrant, trans, racialised, whatever – are just as human as ours. That we are not required to understand or even empathise, in fact: only to share our solidarity and resources as unconditionally as possible.

Which other female non-fiction writers inspire you and why? Any particular title?

Sara Ahmed’s writing – The Promise of Happiness and Queer Phenomenology in particular – is very important to me. Her work shows us that queerness is a direction of travel, a way of being orientated – or, crucially, not orientated – towards things or people; and that one might prefer to be educated than to be happy. Jenny Diski’s memoir Skating To Antarctica gave me my first sense that I could write in a style which might be suppressed, hostile, displeased and displeasing. And it’s quite academic, I know, but Anne-Lise François’ Open Secrets – a book on the tiny, imperceptible, non-events in Romantic and Victorian literature – helped me, at the age of twenty, to understand the intensity in things which don’t happen, or which hardly happen.

What is the best piece of writing advice you have ever received?

I think all the time about Doris Lessing’s advice: ‘Whatever you’re meant to do, do it now. The conditions are always impossible.’ They are always impossible, especially if you’re a woman, extra-especially if you’re a woman of colour. You have to be really ruthless if you want to write (I have accepted that I won’t have most of the trappings of a ‘normal’ life); you have to do it even when it feels terrible; and, as much as possible, you should avoid complaining, unless you’re funny about it. I remind myself that there are lots of important things to do in this world other than writing: no one’s forcing me. This sounds gloomy, but ironically it lifts the pressure off: it makes me excited to write all over again. What a treat!

What book is currently on your nightstand?

I’ve just received a proof copy of Adventures in Volcanoland by Tamsin Mather, which I’m very excited to start. I spent Christmas memorising the different eras of geological time, and pondering the incredible brevity of humans’ time on earth. We’ve been around so much less time than the dinosaurs!