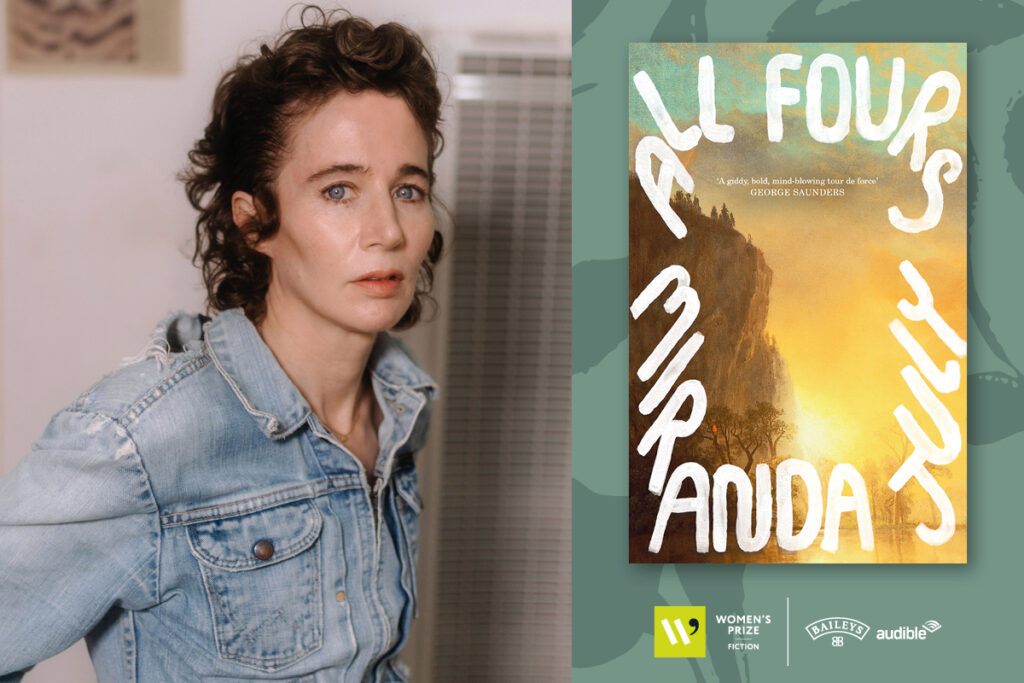

All Fours by Miranda July follows an artist’s quest for a new kind of freedom in her mid-forties.

Shortlisted for the 2025 Women’s Prize for Fiction, judge Amelia Warner says: ‘This is a conversation sparking book which I absolutely loved. There is so much to it that I needed to discuss, the minute I finished it I ordered copies for my friends. It feels like part manifesto, part battle cry for women making sense of a new stage of their life.’

To find out more about the book we spoke to Miranda about her inspirations, writing process and favourite books.

How would you describe your book to a new reader?

All Fours follows an unnamed woman character who is 45. She decides to go on a kind of vision quest road trip, driving from LA to New York, says goodbye to her husband and child, sets out and stops about 20 minutes from her house and checks into a motel and spends the three weeks that she’s supposed to be in New York there. And when she goes home from this supposed road trip, she doesn’t fit back into her life in the same way.

I was looking for this book; a super modern book that didn’t describe this midlife crisis. Whenever people use that phrase, it’s always a joke. It’s never said with a lot of empathy or faith in that person’s process. But aren’t all crises transformative? The plan is to keep changing and not calcify. When I look around at people my age and someone is not going through some kind of upheaval, I wonder if they’re asleep at the wheel or if it’s happening inside and they’re not showing it. It’s unavoidable because you look ahead and instead of seeing middle age, accomplishment, and an open-ended, hopeful space, you see death. And that’s not open-ended, to the best of my knowledge right now. That’s going to be a perspective shift and quite frankly, this is what my friends and I are talking about.

What was the idea that sparked your novel?

While I was shooting my latest feature film, Kajillionaire, I was also occasionally throwing notes into a file called “novel 2.” Many of the notes were about aging and femininity. Also sexuality and marriage. Also motherhood and PTSD. I also wanted to write something about heterosexual lust and romance from a woman’s POV because I had never really done that and it felt embarrassing, taboo. By the time I sat down to write a proposal for the book I had triangulated a space that felt fertile but totally unmapped. Over the course of writing novel 2 my own relationship to every one of these topics changed radically, in ways I could not have foreseen. That constant unmooring became something I was determined to capture in fiction.

And most women, for all of human history, have been told nothing. Even just a few years ago all I had was WebMD and a Mary Ruefle poem called Pause. Thankfully, that has started changing extremely recently, finally it’s getting talked about more, so I’m happy to be a voice among many. For this novel I did a lot of research, I talked to many gynaecologists, naturopaths, interviewed so many women, but of course, ultimately this is a work of fiction, so eventually I had to put that all aside. My narrator is fairly horrified and the facts are only relevant to the degree that they relate to her desires, her plans. Because while we do need to be educated, I see this physical, emotional change as a major theme—so just as with birth, or sex or death, we need stories, operas, songs—we need many contradictory lived accounts, that are unreliable, shape-shifty just like the experience of perimenopause. I see this part of the novel as pretty exciting and new, it makes me kind of giddy to picture women reading it.

Which part of the book did you write first? Was there a moment that clicked a lot of things in place or where you felt the strands of the book started to come together?

I avoided the start for a long time (I find beginnings hard) and focused on the fun Davey section. I also wrote the final scene of her watching him dance. The start was eventually solved by finding an old piece of writing and putting it there – and this piece had a bunch of bits hanging off of it – the telephotographer’s note, for example – that ended up shaping a lot of the book. Parts 2 and 3 changed many times, I was too ambitious in a way. When I cut a bunch of more well-rounded, inclusive, educating material about menopause and focused in on this one woman’s experience the path to the end became clear.

Which part of the book was the most fun to write? Which was the most challenging?

I often found myself writing scenes of desire really easily. In the book, sex doesn’t happen how you think it’s going to happen, and then suddenly, there it is. I wanted to show this very erratic kind of desire because I don’t think women are particularly consistent when it comes down to it. And why would we be? Why is that the expectation? We’re living cyclically and if it has to do with the body, which I’d love it to, then we feel really different ways. It was important to also show what it’s like to not feel desire and to feel aroused in ways that don’t seem hot, in ugly and problematic ways.

Some of it made me uncomfortable to write, or even think about. Who wants to focus on the fear that as you age you will be divested of your power along with your sexuality? But I’m operating within the school of thought that if I don’t engage with my anxieties, if I leave them festering in the shadows, they will swell and haunt me for all the rest of my days; they will mess with my understanding of myself and my relationships and my work. So writing was a way to form a conscious connection with mid-life, and it wasn’t just prophylactic — I began to realize that as I churned through this icky stuff, I started getting kind of high. The humiliating future that had been described to me kind of melted away and in its place was all this room, this freedom.

What is the best piece of writing advice you have ever received?

“Fiction is the lie that tells the truth” is always very liberating to me.

Which female author would you say has impacted your work the most?

There is not one and I’m kind of aghast at having to single out one. I’ll choose my friend Sheila Heti because she is my closest writer friend. Which means not only that I learn from watching her process, reading drafts of her work, but also from her reading mine. She has made some great edits over the years. And when we reject each other’s edits I kind of marvel at how personal voice is, just a single word being changed can suddenly make your shoe feel like someone else’s. Right for their foot, but not yours.

Could you reveal a secret about your creative process?

For the four years I was writing this book I wrote my dream down every morning. I never looked back at them or used the dreams in the book, but I think paying this compliment to my unconscious, first thing, kind of set the course for the day of writing – which for me is a day of wrestling with mystery and shame, the submerged world.