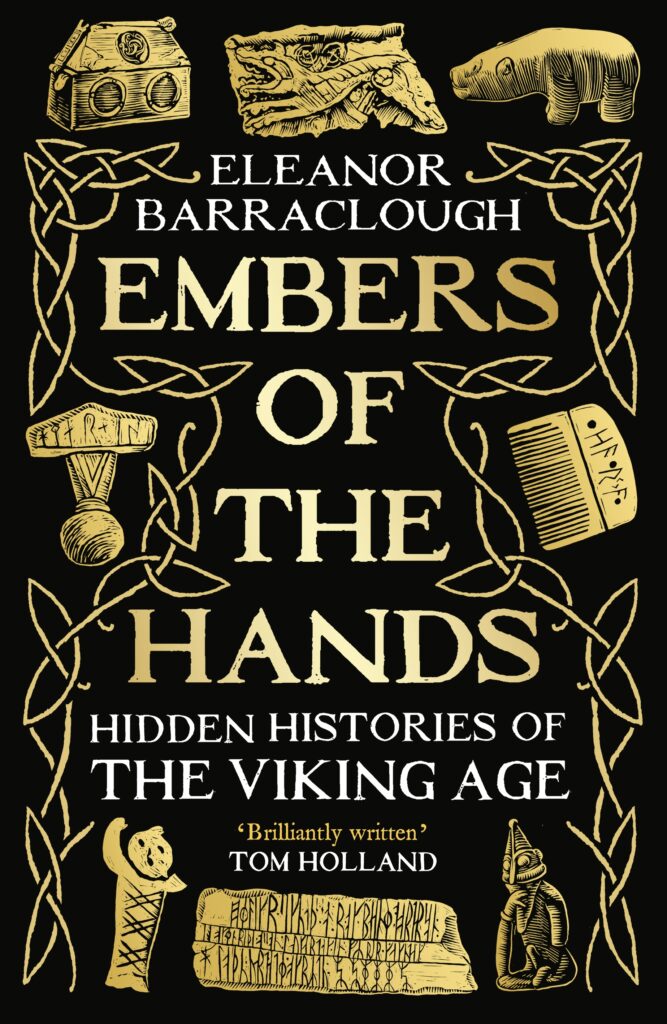

Embers of the Hands: Hidden Histories of the Viking Age by Eleanor Barraclough illuminates the history of the Viking age through everyday objects of ordinary people.

Longlisted for the Women’s Prize for Non-Fiction 2025, judge Emma Gannon says: ‘An accessible gateway into this period using thematic storytelling to paint a fascinating picture of a very different era. It has both lightness of touch and extreme authority making it extremely readable. This book brings us an exciting new talent and I look forward to following all future work by this author.’

Read on to find out more about the book we spoke to Eleanor about her writing, research and current reads.

How would you describe your book to a new reader?

This is a history of the Viking Age on a global stage, told through the stories of everyday humans who fell between the cracks of history, and the little fragments of their lives – ‘embers of the hands’ – that survive down to the present day.

Did you have any revelation moments when writing your book? When the narrative and your objectives all fell into place?

It came in fits and starts. When I look back at my early notebooks, structure was definitely something that had to be figured out. My partner is also a writer and historian, and I remember walking round and round the streets with him in the freezing winter rain, our sickly newborn baby strapped to my front, in the one precious hour we had between him coming home from work and us having to pick up our 1 year old from nursery. I knew what sort of artefacts I wanted to use, what sort of ideas I wanted to explore, but it was really hard to work out how to make a coherent narrative out of it all. Also, this was pandemic lockdown 3 and we were so worn down and sleep-deprived we could barely string a sentence together. The writing in the notebook is all wobbly because we’d be balancing it on a wall, trying to write down ideas, and the ink is all smudged and blotchy because of all the rain. But cracking the structure was a big relief. I wouldn’t say it all fell into place after that, though. There are bits of the book where the writing flowed – I remember the start of Chapter 3, set in wet soggy Bergen, was one of those moments. But most of the time it was me sending a text message to my agent saying ‘I can’t do this I am doooooomed’, or my partner finding me lying face down on the floor saying ‘I can’t do this I am dooooooomed.’ Apparently I’m like this every time I write a book (and my mum says I was the same when I wrote my PhD), but afterwards I can never remember how much doom there was. Writing is always easy afterwards.

What is the one thing you’d like a reader to take away from reading your book?

History isn’t a series of canal locks, all neatly compartmentalised into eras and locations. It’s a rushing flowing river that branches and divides and joins up again, and the humans being bobbed along on its currents don’t necessarily know where the river is taking them, or where it will all end up. The same is true of the humans themselves: they’re complex, contradictory creatures. But it’s those spaces between the certainties, the incongruities and the unknowns, that make history, and humans, so fascinating.

How did you go about researching your book? What resources did you find the most helpful?

I love to get out and about for my research – the wilder (and usually wetter, and/or snowier) the better. I’ve followed Viking far-travellers across the world: to Greenland, Iceland, Arctic Scandinavia, Rome, Istanbul, all sorts. But just as I signed the contract for Embers of the Hands, the pandemic hit. Before long I was stuck at home with a 1-year-old and a newborn, trying to have phone calls with my agent while mopping up baby vomit. And of course no wild adventures, which was a bit tough for someone who loves researching out in the field. As the world gradually opened up again, I found ways to get out into it – we took our two babes on a roadtrip across Europe, all the way to Denmark, with suitcases full of baked beans, baby snacks and nappies. On another occasion, I was making a BBC radio documentary about runes, up in Orkney – we had to take the babes there too, not least because I was breastfeeding. But that was a great place to gather information, and there’s a lot of runic material in my book as a result. And the babes got to toddle in and out of pitch-black chambered cairns with torches as I hunted for runic inscriptions on the walls, and hang out with a giant stuffed puffin called Magnus. But I feel there’s an intimacy to Embers of the Hands that comes from the nature of how so much of it was conceived of and written, especially in the early stages. I hope that translates into sense of getting closer to the people of the past, and the extraordinary ordinariness of their experiences, beliefs and emotions.

Which female non-fiction author would you say has impacted your work the most?

There are many, but particularly Mary Beard, not only because she writes with such humanity, humour, and intelligence, but also because she transforms vulnerabilities into superpowers. Years ago, when I was a postdoctoral researcher at Oxford, Mary wrote a piece about how people don’t talk about their failures, in the context of having been turned down for a professorship. I myself had just been turned down for a research fellowship and was feeling pretty dejected. I emailed to thank her for her wise words, not expecting a reply. Nine minutes later, there was a message from her in my inbox, thanking me (!) for making her feel better about having put those thoughts out into the world. This has had a huge impact on my work over the years: I find I write a lot better when I make space for vulnerability, uncertainty and the possibility of failure. Mary has taught me to be brave about how I write and who I write for. (Also, can we please take a moment to appreciate her brilliant footwear.)

What is the best piece of writing advice you have ever received?

I’m lucky to be surrounded by wise humans, many of them writers themselves, who have given me all sorts of brilliant writing advice over the years. But one of the best pieces was from Mary Beard’s email to me: ‘We’ve all been taught to keep quiet about our failures, so success ends up looking effortless, when actually it’s dotted with failure.’ Those words have always stuck with me. As a perfectionist, I tend to beat myself up if I’m struggling to write, and I frequently find myself chugging along on the authorial struggle bus. It’s good to be reminded that successful writing is a palimpsest, and there’s plenty of unsuccessful writing underneath what you see on the page.

Is there a non-fiction book you recommend all the time? If so, what is it and why do you recommend it?

I couldn’t just recommend one! That’s the beauty of books, there are so many wonderful ones out there, and different people suit different books at different times. Right now I’m going through a non-fiction graphic novel phase – I have quite a short attention span, and it’s such a wonderful format for bringing together facts, research dialogues, humour and poignancy. The ones I’ve been pressing, wild-eyed, into the hands of my friends and family include: World Without End by Jancovici and Blain, Sapiens: A Graphic History by Harari, Vandermeulen and Casanave, and The Story of Sex by Brenot and Coryn.

In terms of subject matter, it would be The Greenlanders by Jane Smiley. Historical fiction can be every bit as important and meaningful as historical non-fiction, and I’m always recommending this one. The book is meticulously researched, and populated with the all the colour, drama and emotion of the human experience. I’m fascinated by the whole mysterious business of the Norse Greenlandic colony, which I’ve researched since I was a PhD student (it features heavily in Embers of the Hands). I’ve also researched out there myself, first on horseback with a very badass horsewoman as my guide, then by boat with two equally badass caribou hunters. But it was only when I read The Greenlanders that all the bits started to fall into place, and I started to understand these ruined farmsteads and churches and fields as a community once populated by real people.

What are you currently reading?

I’m working my way through S.G. Maclean’s Seeker series – historical fiction / political thriller set in London during Cromwell’s Protectorate. My wonderful friend gave me the entire set for Christmas while I had the flu, and I’m absolutely gripped. Then part of the joy of writing is that you get to get sneak previews of other people’s writing, so I’m also reading proofs of three fascinating non-fiction books: Proto by Laura Spinney, Between Two Rivers by Moudhy Al-Rashid and Apocalyptic Ecologies by Shannon Gayk.