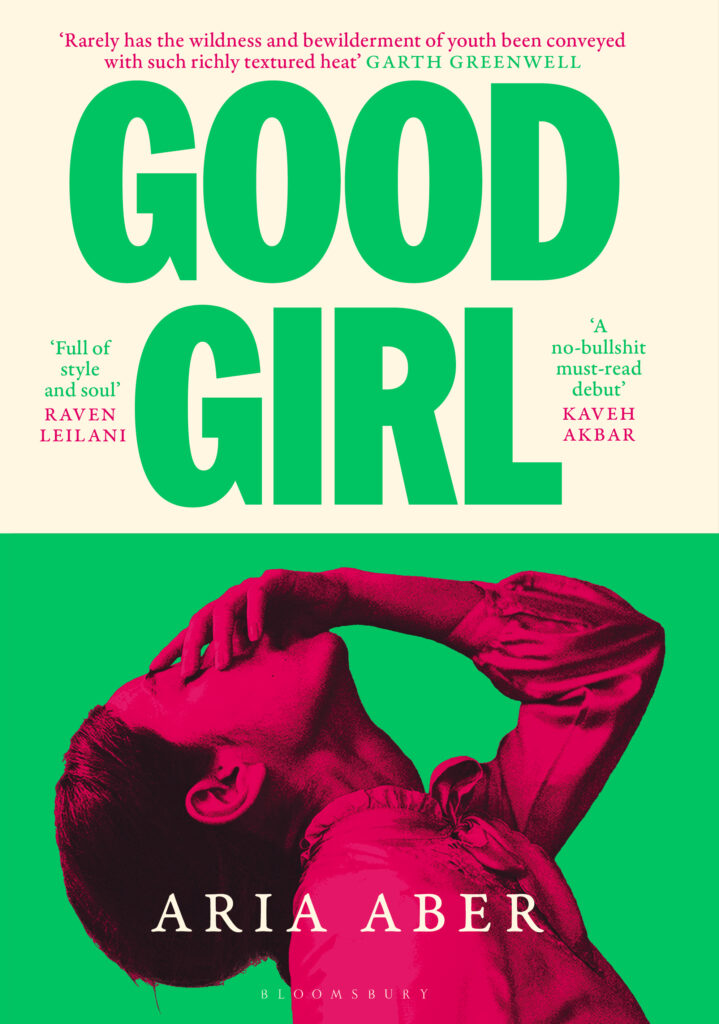

Good Girl by Aria Aber describes a young woman’s attempt to leave behind the legacy of her immigrant parents by reinventing herself within Berlin’s artistic community.

Shortlisted for the 2025 Women’s Prize for Fiction, judge Diana Evans says: ‘This is an emotive, psychedelic novel whose writing is both poetic and politically powerful. Set in Berlin’s artistic underground and nightclub scene, it follows Nila, a young woman born to Afghan parents as she comes to terms with her identity against a backdrop of anti-Muslim terrorism. It’s beautifully written, disarmingly so – I’ve never read sentences quite like this.’

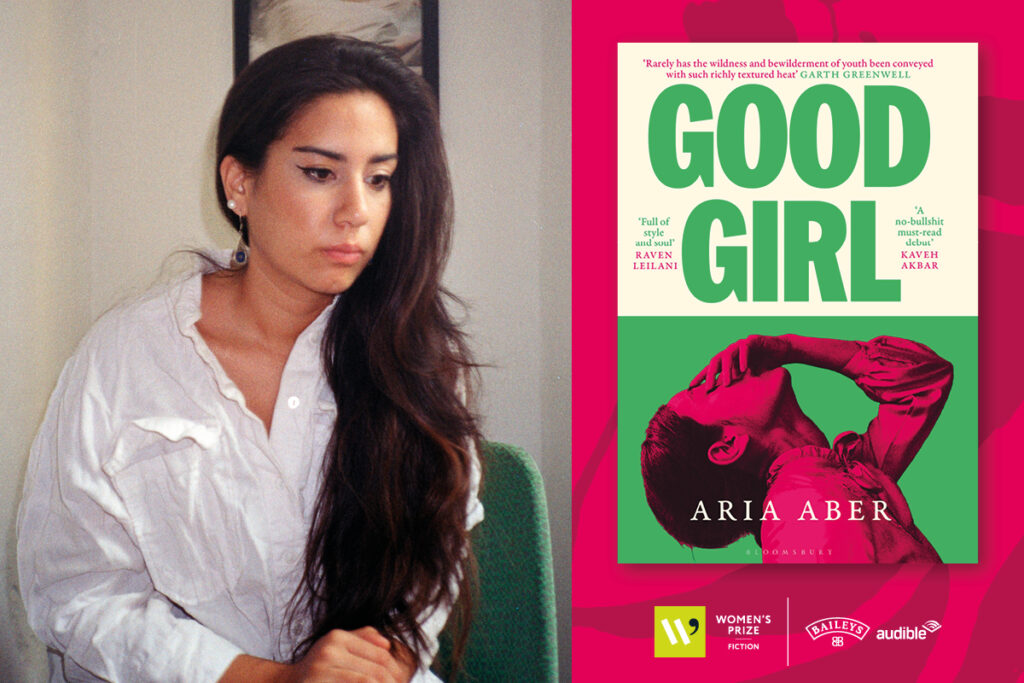

To find out more about the book we spoke to Aria about her inspirations, writing process and favourite books.

How would you describe your book to a new reader?

Good Girl is a bildungsroman that follows 19-year-old Nila, an aspiring photographer, on her trials and tribulations through Berlin’s nightlife scene. She is the daughter of Afghan refugees, and lies about where she is from. Early on, she falls in love with Marlowe, an older American writer, and together they delve into the club scene at the Bunker. But the novel isn’t just about art and sex and drugs and friendship, it’s also about violence on a national and domestic level.

What was the idea that sparked your novel?

I had always wanted to write a book about a young Afghan woman trying to find herself in a big European city, because I hadn’t encountered that type of narrative before. Of course, the conventions of my book are by now commonplace in contemporary literature, especially in Germany (sad girl goes to Berghain and falls in love with a toxic man), but the nuances of my own positionality upend the trope that I was so interested in––and I mainly was reading writers such as Jean Rhys, Marguerite Duras, and James Baldwin when I got inspired to write the book, because all three manage to follow exiled protagonists adrift in a European city. The post-colonial and mid-century mentality felt very relevant to my own experience as the child of Afghan refugees, who struggled with questions on war, exile, tradition, Marxism, and the dying dream of a better world at the turn of the new Millennium.

Which part of the book did you write first? Was there a moment that clicked a lot of things in place or where you felt the strands of the book started to come together?

The first chapters I wrote comprise the last fourth of the book––those practically came to me in a flow state while I was living in Berlin in 2020. It was magical and totally unexpected to begin with the ending, which is not something I was used to as a poet. From then on, the challenge was figuring out who Nila, the protagonist who had emerged, was and how she got to that point of transformation in her journey. What made the narrative click for me, ultimately, was the decision to frame the novel in a moment of retrospection, and have Nila narrate it as an adult looking back. That way, I could focus on the Neo-Nazi violence that builds the background of those years in Germany. Her reluctance to accept herself and her heritage, her larger community, abruptly changes because of this exterior violent event, which forces her to come to terms with her identity. It is the beginning of a political awakening, not just a personal and artistic one, that transforms Nila’s personality and catapults her into adulthood.

Which part of the book was the most fun to write? Which was the most challenging?

The club scenes were incredibly exhilarating but also quite exhausting to write. The novel is not autobiographical, but I did spend a substantial amount of time in Germany’s nightlife scene, so there was a lot of personal data to draw from. I listened to old techno and house sets, read through German blogs and articles from the early 2000s, and interviewed some of my friends to refresh my memory of what clubbing felt like back then. I also quite enjoyed writing the childhood chapters, as they’re removed from the present-day narrative of the novel, and I felt the liberty to be more fragmentary and musical in them, as if they were prose poems. The biggest challenge, interestingly, was creating real, complex, sometimes violent and yet tender and loving parental characters for Nila. The mother figure, who is very difficult and mysterious, drew too much attention to herself; in fact, I made the craft decision to make her pass away early on so that I could get away with the lacuna and obscurity of her being.

What is the best piece of writing advice you have ever received?

My late mentor Louise Glück always said to me that the quality she most looks for in writing is the feeling of the language ‘being alive’. I have never forgotten it. I think there are many ways to interpret it aesthetically and philosophically, but mostly, I think of ‘aliveness’ as a real heart that throbs underneath the writing, be it a poem, a piece of non-fiction, or a novel. One must take risks with their medium, which for us writers is language itself. I also love what Solmaz Sharif says, quoting, I think, her professor Yusef Komunyaaka, that ‘poets are the caretakers of language.’ I try to think of this ethical theorem when I sit down to write. What does it mean to take care of language, when language is being used to create policies that dehumanize, segregate, and ultimately kill entire people? What does it mean to enter the anglophone tradition, and speak back to the past and also the future? What is our responsibility as writers in the lingua franca of the world?

Which female author would you say has impacted your work the most?

Jean Rhys was the first writer I felt like saved my life. But more recently, it has been Nawal El Saadawi.

What is your favourite book from the Women’s Prize library and why?

There are so many writers from the library that I absolutely adore – Leila Aboulela, Rachel Cusk, Sally Rooney, Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, Arundhati Roy. But my favourite books from the more recent years include Luster by Raven Leilani, because of its irreverent, piercing prose and its humor. I read it in a day and felt completely spellbound by it. I also loved Hangman by Maya Binyam, for its original, smart, Kafkaesque construction. What a triumph. How to Say Babylon by Safiya Sinclair is a memoir that’s very close to my heart, and I feel like I always learn so much from Sinclair’s incredible sentences. She writes like no other. And, perhaps most recently and importantly, the extraordinary novel Enter Ghost by Isabella Hammad. That book arrived in my hands at a time when I really needed it. I deeply admire the ethics and clarity of her voice. I feel a deep kinship with her writing.

Could you reveal a secret about your creative process?

I love writing at night, after everyone has gone to sleep. I also love writing in my own bed, and sometimes in the bathtub, where I either draft in a notebook or on my phone’s Notes App. Whenever I feel stuck, I listen to my mother’s advice and go on a walk. Generally, being in motion––in a car, or on a train, or plane––unlocks a part of my creativity and helps me figure out craft problems in my writing.