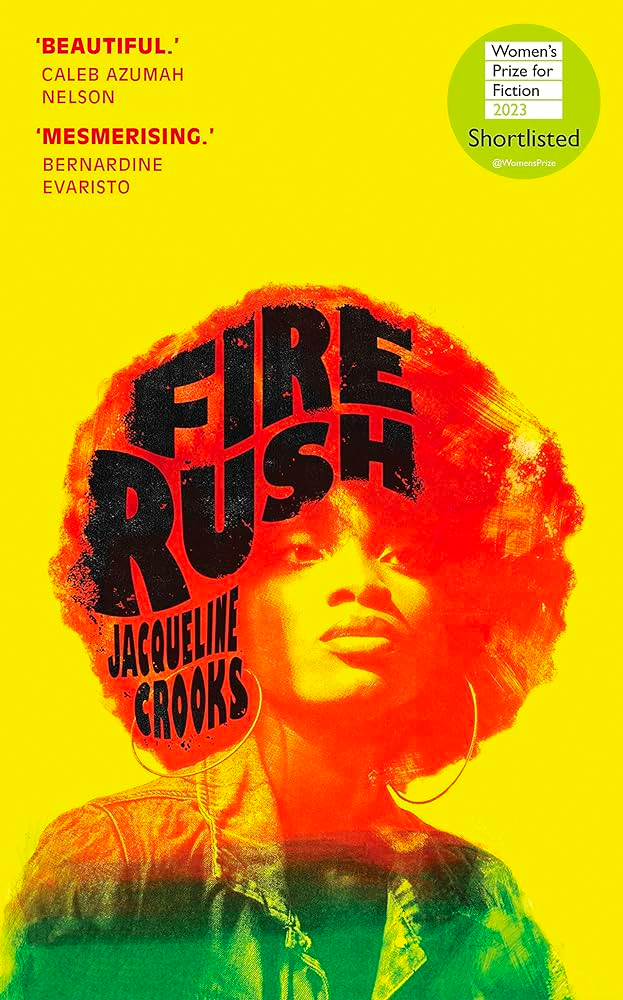

Meet Jacqueline Crooks, author of the Women’s Prize 2023 longlisted novel Fire Rush. A novel which The Telegraph has said, “tackles race riots, grief, youth culture and the transcendence of dub music.”

The premise of this book is powerful and unique, so what was the inspiration behind the novel? We grabbed a quick five minutes with each of the authors behind the longlisted books to ask that question and more…

Describe your novel in one sentence as if you were telling a friend.

The quest of a woman within the male-dominated dub-reggae underworld to use supra-watt dub music power to find sites of safety for her mind and body.

What inspired you to write Fire Rush?

The dub reggae sound revolution of the 1970s and 1980s was an important moment in time, and the culture of that world continues to reverberate, impacting on the fashion, music, and language of today. It was a hidden subterranean world, and it struck me that many people didn’t know of its existence. I wanted to explore through writing the politics of invisibility and was compelled to write about this hidden world, and recreate it from memory and imagination. It felt imperative to privilege a woman’s perspective in this male-dominated world. Yamaye, the protagonist, is based on my experiences in that subterranean culture. I don’t think there is anything else out there in terms of fiction that platforms a woman’s perspective from that subterranean world of DJs, Stix-Men, skankers, and crutchers – hustlers. Also, I had only ever found books about dub reggae written by men. I wanted to write about this world from a woman’s perspective as I hadn’t found a book that was doing this. I wanted to foreground a woman’s experience in the seminal time of the Black sound revolution and show the different ways in which women rebel and also the ways they express rage.

Are there any locations that have a special connection for you or your book?

I was born in a rural village in Jamaica and came to London as part of the Windrush community, so I felt a special connection to Cockpit Country in Jamaica and enjoyed setting parts of the story in this landscape. I haven’t been back to Jamaica for many years and so setting some of the story in rural Jamaica was a way of reconnecting to the island through imagination and fragments of memory. I tried to conjure the haunting magic of that landscape. Remembering and imagining it as soundscape, textual space, liminal space, an empowered and nurturing space, bush geographies inhabited by Super Sonic Black Women rebels such as Queen Nanny of the Maroons.

Which part of the book was the most fun to write? Which was the most challenging?

I loved writing the scene where Yamaye is driving the getaway car, evading the police and speeding through the streets of Bristol. In fiction, it’s often the men at the wheels of the car or the plane or running ahead and leading the way. I had an experience that was very similar to that scene where I was driving a car with three men who were getting away from a gang. So I enjoyed drawing on that experience and using artistic licence to bring in elements of history where women used their bodies as vessels to escape slavery.

I especially enjoyed writing the scenes where Yamaye is on the decks at her Sonic Dominatrix club night, singing and toasting on the mic, controlling the crowd. It was satisfying to get her lyrics onto the page and have them as a kind of sounding between the prose. Yamaye is not in control of her life at certain moments, but she is always in control at her club nights. It was important not to have a woman protagonist who is purely a victim.

It was challenging to write some of the scenes where Yamaye is being sexually exploited. It is a huge responsibility to write scenes like this and to somehow protect the woman’s spirit on the page. Having myself experienced sexual violence within this underground world, it was important to me to explore this in the novel as a survivalist and not shy away from it. I wanted to write the sexual exploitation scenes to show the violence of an attack against the mind as well as against the body.

Which of the characters from the book would you most like to spend a weekend away with and why?

I’d like to spend a weekend away with two men for different reasons.

First, with Moose. He is an amalgamation of a couple of the good men that I turned my nose up at when I was younger because I didn’t know how to value goodness, kindness, and stability. I’d like to go to that cabin in Scotland and get snowed in for the weekend. At the age of 60, with all the awareness and confidence that comes with age, I would value that kind of solid, dependable, loving man. I think it would be a memorable weekend.

Second, I would like to spend the weekend away with Herbert Peters. Herbert Peters is based on Peter Herbert OBE, the barrister and political activist who fights against racism and injustice (He gave me permission to draw on his life and also helped with research). I’d like to spend the weekend find out more about what drives him to stay on the front line of activism, taking on superstructures. I’d like to find out more about his work, especially in the 1970s. I’d like to find out what he thinks about Fire Rush and the position of women on the front line who experience violence from within their own community. I like to know whether he thinks fiction can have a political impact and be the starting point for communication and engagement between opposing ideas or people.

What first inspired you to write?

I met my maternal Indian grandfather in Jamaica for the first time in 1988. He was the son of Indian indentured labourers. I was fascinated by this Indian man in a rural sugar plantation village in Jamaica and the hybridity of his life. He was blind, and we spent a lot of time talking about his life. He was a living archive, and I was inspired to write his life story as a way of archiving it. I played with the idea for many years and started going to small writing workshops, but I didn’t start writing anything properly until 2000. The more I researched my family’s history, the more I became entranced by my ancestors, and I started to write about my great-grandparents. Eventually, the stories became a collection of short stories spanning Siberia, India, Germany, Jamaica, and England as I explored my family’s history and geography. It was a way of exploring the hybridity of my own life as an Indo-Caribbean Jamaican woman living in London and straddling multiple cultures.

What is the best piece of writing advice you have received?

Trust your voice, no one else’s.