From the Women’s Prize Archives.

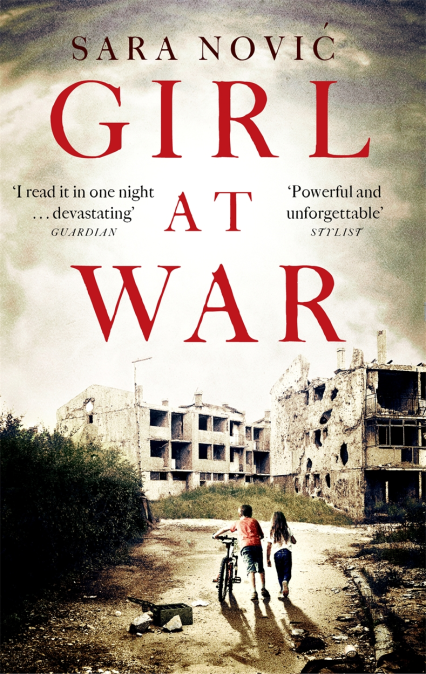

We caught up with 2016 Baileys Women’s Prize longlisted author Sara Novic to find out about why she was inspired to write her longlisted book Girl at War about the Bosnian-Croat conflict, which writers particularly influence her work and why the US commuter rail can be a great place to write a novel.

Why did you want to set your novel against the backdrop of the Bosnian-Croat war?

I was living with family for a bit in Croatia after high school, and throughout that time I wrote down many stories about people’s experiences during the war. I had no particular plans for doing anything with the stories, but I felt they were important and should be recorded; had always been an avid journaller and so writing them down came naturally to me. Then when I returned to the States to start uni I was shocked to find that a lot of my peers hadn’t heard about the war, or didn’t even know where the ex-Yugo countries were on a map. Somewhat accidentally, I enrolled in a creative writing class and wrote a story, mostly out of anger, about a young boy who has a traumatic experience and then struggles to deal with it, and explain it to his American peers, in adulthood. My professor called me to his office and encouraged me to expand on the project. I had no real idea what I was doing in terms of the craft, but I knew I felt strongly about the story and about other people understanding the war, so I kept working on it. Though the initial character changed from a boy to a girl over time, the crux of that first story lies pretty much intact at the end of part one in the book now.

Did you do any particular research to enable you to write so convincingly about both the horrors and the mundanity of war?

I was pretty relentless in my questioning of friends and family throughout the writing of this book, and was lucky that they were very encouraging of the project and read the manuscript at various stages. I also read every book on the subject I could get my hands on, and looked at lots of news reports and maps of troop movements. I even did some almost silly research–like what was the weather on a given date–I don’t know why, but that felt important to me, and would change the way the characters experienced an event. That war can be very boring–repetitive, a lot of sitting or standing in line waiting, rationing everything–is not part of the narrative we get from the news; they cut out all the boring bits. But the fact that life in this war was still life–modern, TV-watching life just like the rest of Europe–was something I wanted to highlight in the book, mainly because the people who had survived the war firsthand were my most important sources, and I found that to be a connecting thread in a lot of their stories.

Why did you choose to narrate the story through the eyes of a ten-year-old girl?

As I said, originally the character I had in mind was a boy, though of the same age. I can’t pinpoint the conscious reason why the narrator morphed into a girl, but I’m glad it happened, because women and girls are not often thought about in the context of wars, but they are equally (if not more) affected by them, particularly in this war, in which rape warfare was a big factor. The child’s point-of-view also afforded the reader the ability to learn about the war alongside the narrator, which was helpful in a war as complex as this. Additionally, Ana initially has a simplified understanding of what happened in the war, and that gets complicated when she returns as an adult, which I think is also an important component of understanding this or any war.

Were you inspired by any other authors whilst writing Girl at War?

The two writers that appear overtly in the novel–Sebald and Rebecca West–were obviously huge influences on me as a writer/ human whilst working on this project. The way Sebald discusses memory and trauma was a big part of why I wanted Girl at War to move back and forth in time rather than read chronologically. Fragmentation is such a large part of so many victims’ experiences, and I knew I wanted that to be reflected somehow in the novel. I learned a lot from Holocaust survivors’ works–Primo Levi and Tadeusz Borowski in particular–about how to write unflinchingly about the horrors of war. The Bosnian poet Izet Sarajlić, also taught me a lot about the function of humor in a war narrative. The game-playing that Ana and her friends participate in midst the war was something that came up in so many friends’ stories, and I found the humor in Sarajlić’s work so effective that I knew I needed to include those moments of levity as part of the authentic experience of childhood in a war zone.

As far as writerly inspirations disconnected from this specific project, I’ve always been a huge Zadie Smith fangirl; her work is witty and engrossing and completely brilliant, and those are things to which I think any writer aspires.

Do you have a particular place where you like to write?

I usually write by hand, and somewhere in public, like a library or cafe, because being out of my flat stops me from procrastinating! I wrote a lot of Girl at War on the commuter rail when I was working in Philadelphia and taking writing classes at Columbia in New York City. That train was a great place to write because there was no internet, nothing interesting to look at and nowhere to go, so I just had to sit in the seat and work.