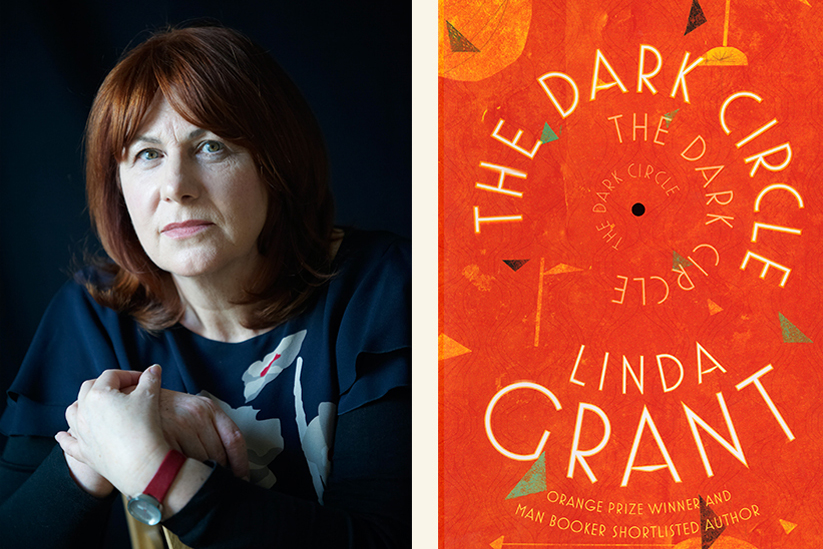

From the Women’s Prize Archives.

The brilliant 2000 Baileys Women’s Prize for Fiction winner Linda Grant has been longlisted for this year’s Prize for The Dark Circle. Read on to learn about Linda’s research methods, how to put the social media hive mind to good use and why the death of the book might not be imminent.

You won the Women’s Prize for When I Lived in Modern Times in 2000, what impact did this have on your career and your work?

It was huge. It changed the direction of my life because it gave me money to stop doing journalism and write full-time. It brought me international publishers and increased advances and in low moments of self-doubt I have looked up at the statue on my bookshelf and thought, ‘They can’t take that away from me.’ Nor that marvellous night, almost speechless as my name was announced and nothing prepared and all the flashes going off in my face, so very very different from the writing itself, which is done in hunched solitude and privacy.

Once you said the death of the book might be the most adverse thing which could happen in your lifetime. Do you still think this might occur within your lifetime?

Not in mine, no. I think there has been a huge resurgence of the book as the novelty of the e-reader has worn off. More worrying is whether future generations will want to read books in any format. I have a five-month-old great-niece and I have stocked her with books far in advance of her current interest in chewing them. Her mother says she already has more books than she herself ever had. That stuns me, because as a child all I did was read.

In The Dark Circle, you write about the founding years of the NHS in the 1950s. Did you do any particular research?

I did two long interviews with a woman who was x-rayed to take up her place at university in 1949. It was when she told me about the sanatorium going over to the NHS and a new influx off patients mixing with the middle-classes, that I knew that there was a story and a novel. I did read up on the history of the disease and its treatments and of course Thomas Mann’s The Magic Mountain and other novels about TB. It has been a rich source for novelists because it involves so much lying around thinking morbid thoughts.

Originally, you were a journalist, what made you make the leap into fiction?

That’s quite funny. I’ve never seen the distinction, both are about telling stories. I became a journalist because it was a means of being paid to knock on the doors of strangers and ask them personal questions and then write about what they had told me, while I was waiting to have a novel to write.

You’re very active on Twitter – do you find social media a hinderance or a help when you write?

Because of Twitter I’ve first virtually met, then met in real life, the pianist Stephen Hough and been to some of his concerts, so yes, it can be a tremendous waste of time and I’m much less active since most of it seems to be memes about Trump, but it has its uses – particularly when you want to consult the hive mind for research.