From the Women’s Prize Archives.

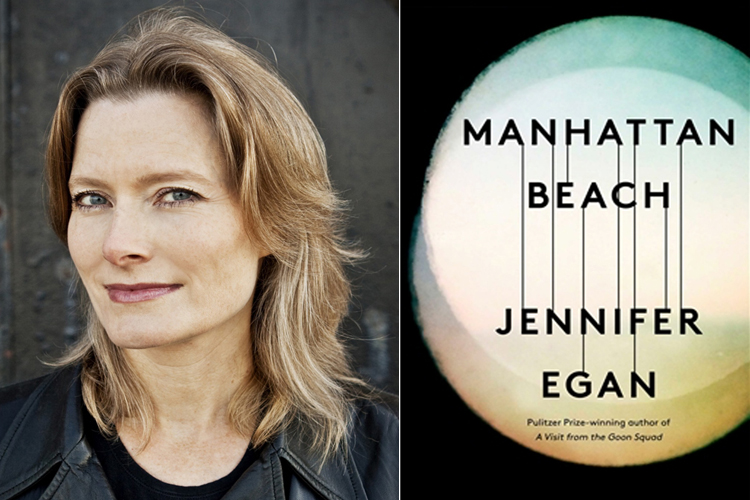

Jennifer Egan has been longlisted for the 2018 Women’s Prize for Fiction for Manhattan Beach. Read on to find out about the mammoth amount of research she had to do to write through the eyes of WWII-era diver, and why the narrative techniques she used in her bestselling A Visit From The Goon Squad had to be changed up in her latest novel.

Did you find Manhattan Beach more challenging to write, following the huge success of your Pulitzer Prize-winning novel A Visit From The Goon Squad?

Manhattan Beach was very challenging to write, but not for that reason. Since I don’t write autobiographically, the mains points of connection between my work and my life are times and places I’ve known. For that reason, I felt uniquely ill-qualified to write a book set outside my lifetime. It took about five years of reading letters and novels and interviewing people—mostly in their 80’s—for me to accrete a sort of alternate memory bank full of textures and details anecdotes I could call upon spontaneously, although they weren’t my own.

Why did you decide to set your latest novel in WWII–era New York?

I’ve been interested in World War II New York for a long time—really, since 9/11, when the city was transformed into a war zone overnight. I liked the idea of imagining World War II New York through a noir lens. Time and place are what I start with; I know when and where a book will take place long before I know who is in it or what they’ll do. In that sense, I don’t really “set” a book anywhere—in fact, closer to the opposite: the setting yields all the rest.

Did you do any particular research to enable you to write through the eyes of a military diver?

Anna is a civilian diver; the distinction is important, because women didn’t dive in the Navy until the 1970’s. And yes, I had to do a mammoth amount of research to be able to write authoritatively about that kind of diving. Some of it was experiential; I attended a reunion of veteran Army divers in 2009 and was dressed in the old Mark V diving suit. Some was journalistic; I spent hours and hours on the phone with divers who had worn that old equipment (and also with the first female Army diver), questioning them about the technicalities and sensations of diving. And finally, I pored over old diving manuals that were extremely technical, learning in detail about every aspect of the equipment. I find in general that in order to write about someone doing any kind of work, you really have to know your stuff.

Did you set out to write such a stridently feminist book?

If a book that is explicitly about female strength is “stridently feminist,” then yes, I did.

Goon Squad was written with many innovations of form, did you consciously decide to depart from this and write a more conventional narrative?

I had originally thought there would be more formal playfulness in Manhattan Beach, but techniques that had worked well in A Visit From The Goon Squad—leaping forward in time, for example—fell flat in this book. They were worse than unsuccessful; they felt annoying and manipulative. I love to experiment with structure because doing so lets me write stories I couldn’t otherwise tell. But this particular story required a different kind of treatment in order to work; here, the extremes are in the action itself. I’ve got shipwreck, murders, survival at sea… and those sorts of events were not well served by fragmentation or winky collusion between reader and writer. And frankly, I didn’t realize how tired I’d become of all that—of myself doing all that—until I finally let it go.