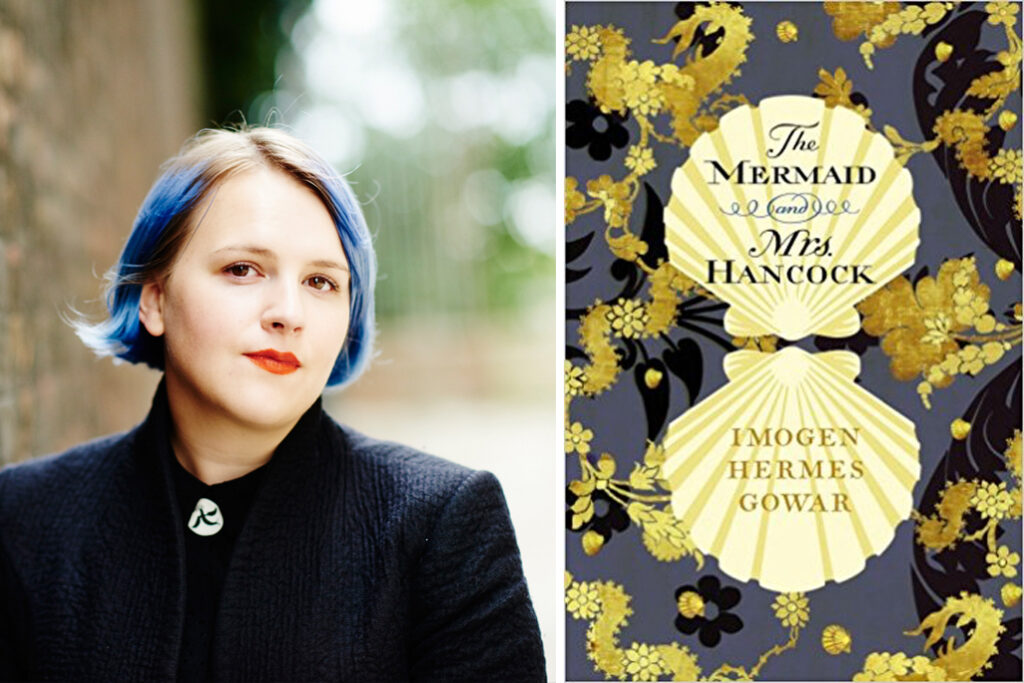

From the Women’s Prize Archives.

The fantastic Imogen Hermes Gowar has been longlisted for the 2018 Women’s Prize for Fiction for The Mermaid and Mrs Hancock. Read on to find out about Imogen’s 10 month research period at the British Library, why it is that mermaids have such enduring appeal and why The Worst Witch was an early inspiration.

Which women writers have most influenced your fiction?

Besides Jill Murphy (I wrote a lot of Worst Witch fan fic when I was six or seven), Joan Aiken was the first author I remember setting out to emulate. The gothic-historic element to her novels and her ghost stories, and her choice of tricksy unusual words really left a mark on me. As an adult, the authors I return to again and again with admiration and a desire to learn are Doris Lessing, Muriel Spark, Shirley Jackson and Beryl Bainbridge. Those are the books I’ll read once for pleasure, and then over and over to try to work out how they were done. In historical fiction, Rose Tremain has been a constant touchstone for me: she seems to revel in writing incredibly flawed characters, and her work can be sexy, funny, mucky, but always empathetic and observant.

You’ve been acclaimed for ‘cresting a new wave of feminist fiction that brings the complex lives of historical women out of the shadows’ – is bringing women’s stories to the forefront something you set out to do?

That was never a conscious decision, but I have always been more interested in women’s stories and women’s history. My issue with ‘traditional’ history – speeches, battles, lawmaking – is not specifically its overwhelming maleness (although of course that’s an issue), it’s that it deals with all the big cultural/political issues and none of the little ones that interest me. It always bothered me that in a lot of writing from/about the past, ‘food was brought in’; ‘a bed was made up’; what human was doing that? What was their life like? The activities of a relatively few people were silently enabled by the labour of many nameless others, who barely featured in the historical record, and right from the start that tantalised me. I found that if I wanted to really learn about the texture and emotion of everyday life, rather than its grand deeds, I needed to look for the people in the back room: working class people; people of colour; but always, always women.

Of course it’s possible to write great fiction about important historical people and moments – and I’d argue that part of what makes Mantel’s Cromwell so engaging is his domestic life – but I like the spaces in between. While researching eighteenth century women I found the same sentiment come up again and again: ‘we were told there were no records; it turns out nobody had looked for them’. I love the wealth of academia and research on historical women that is flourishing now, when it couldn’t have fifty years ago: it excites me that alternative histories are being retrieved, and I think I’m just responding to that with my fiction. It feels like an exercise in enquiry as much as creativity.

What drew you to set your debut in eighteenth century London?

When I walk around London, I’ve always felt the past crowding in. I’ve never been able to think of it as simply a modern city: I’m always thinking about what used to be here; who used to live here; what happened here. London’s past felt very alive to me long before I thought to write the book, so it wasn’t a stretch at all. I was just doing what I love most. Being so familiar with London gave me the confidence: I wouldn’t have undertaken a debut novel set in, say, eighteenth-century Lisbon or Vienna. I’d need to really walk a city before I could write it.

Can you tell us about the research you undertook to allow you to paint this historical period so vividly?

I was on the dole when I started research in earnest, and then I worked in a cafe, so I had to do it all for free. My big outlay was a Thermos flask for lunch. I had about 20,000 words of the novel and knew what my plot was: at that point I got a readers card for the British Library and spent about ten months only researching, without writing a word. I wanted to feel really immersed and comfortable with my period before I began writing it; I think readers can tell when the writer feels shaky about something. I read a lot of current academic research as well as eighteenth century pamphlets, novels and court transcripts (these were great for getting a sense of ‘voice’), but my own academic background is in ‘stuff’ rather than words. I felt most comfortable looking at visual and material culture: cartoons, paintings, clothes, buildings. I walked all round London; I tried to visit everywhere I wrote about, whether or not the buildings were still standing. You discover so much more when you are there in person: there is a real difference between physically understanding something and just academically imagining it.

Why were you inspired to write about mermaids and why do you think they have such enduring appeal?

They’re one of the few emphatically female creatures of folklore, and they wield such serious power: I think it’s the power, strength and autonomy that appeals, rather than bland prettiness or man-pleasing. They’re great to write about because even today they provoke so many responses, of such intensity. The one in The Mermaid and Mrs Hancock is a macguffin, in that the drama is not so much the mermaid itself, but what it provokes the characters to do or to reveal. I’m equally as interested in the idea of mermaid as dubious sideshow freak, erotic fantasy and supernatural threat: I love that those things can exist all at once, and that ambiguity makes so much space to play.

I also wonder whether we think about mermaids the same way we think about extra-terrestrials: we hope we aren’t alone; that the void might be inhabited by entities a bit like us. People still make hoax mermaids. We haven’t stopped wanting them to exist.