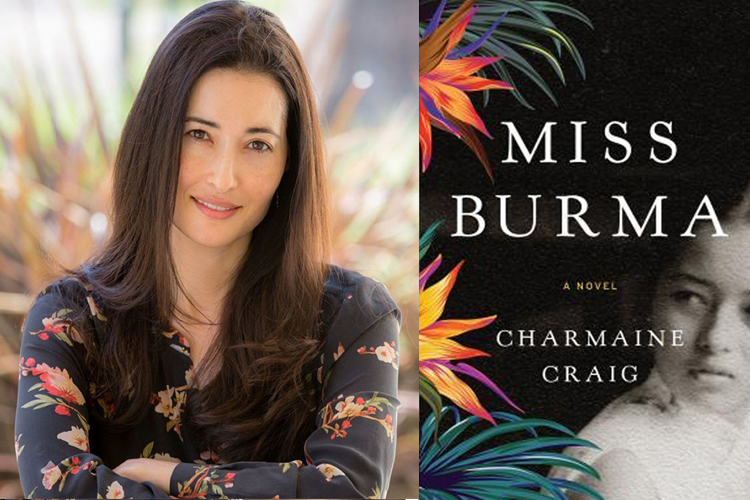

From the Women’s Prize Archives.

The brilliant Charmaine Craig has been longlisted for the 2018 Women’s Prize for Fiction for Miss Burma. Read on to find out how Charmaine’s acting background has affected her fiction and the struggle of documenting both her family history and that of the Karen people.

How has your background as an actress affected the way you write?

As an actor, I learned invaluable lessons about the importance of opposition in art—for example, in a dramatic scene, how the tension between two people will increase if they withhold their deeper feelings from one another. I learned about the necessity of dissonance—say, between what a character discloses about herself through gesture and what she announces in speech. And I learned that scenes gain both excitement and realism when they move to unexpected places. I left acting in my twenties because most of the roles for which I was being considered (often “exotic” girlfriends or extra terrestrial beings) seemed undignified to me, and because the first thing that happens in a casting room when you are a young woman is that you are sized up physically. I have been much happier in the relative obscurity and freedom of my writing life. And I have embraced the distinction of fiction, which is a mediated—or narrated—form whose special subject is the experience of consciousness.

You spent 10 years working on this novel – was it hard to stay motivated?

I continue to choose to write fiction because its difficulty appeals to me. The process of striving through language (and mostly failing) to make something artful and lucid, truthful and arresting, is one that I find deeply consoling. A scene that evokes the depths we swim in when we live, a paragraph that coheres and moves and surprises: to try to write one of those is for me to hope to make contact with an intelligence that supersedes my own. Of course, to write about Burma, which has a complicated and largely undocumented history, was to take on perhaps more difficulty than I would have wished on myself. But even this challenge was ultimately motivating, because it pushed me to discover interstices between the private and the public, the past and the present, and the West and a country often deemed irrelevant by Westerners. Also: I’m stubborn!

Can you tell us what you’re working on now?

To approach a story—a big and difficult and mysterious one—can be like vigilantly stalking an enormous, cagey, unfathomable, and even supernatural creature. One senses its potency, its latent perfection, and one’s own utter inadequacy to the task. What I can say is that I’m working on a novel that attempts to associate themes of faith, womanhood, displacement, and social justice, and that is set, mostly, in contemporary times.

The novel is based on the lives of your mother and grandparents – was it cathartic to write your family’s story?

Writing fiction can also be playful: you’re a child playing house, imagining your way into unknown roles and secret doings and inner lives. And it turns out that make-believe can sometimes bring you into startling contact with others and even with reality. There were moments, during the writing about a character modeled on a deceased family member, when I felt that I was brought inexplicably close to an understanding that I never could have known in real life. Cathartic? Not in the Aristotelian sense. But powerful. Affecting.

The novel is deeply concerned with the Karen people (one of Burma’s larger minority and indigenous ethnic groups), who were systematically suppressed from recording their own history and culture. Was this hard to research?

During the work of the novel, I often felt as though I were blinking into the darkness, because so little has been documented about Karen history, and about the collisions between that history and Burma’s and the West’s. One of my goals became drawing the reader into a similar experience of peering into the shadows of a suppressive state only to be struck by a moment of illumination, when secret alliances and dealings come glaringly to light. But the real challenge for me was to do this while pursuing questions about the meaning and value of human experience, and all through the aperture of character and consciousness.