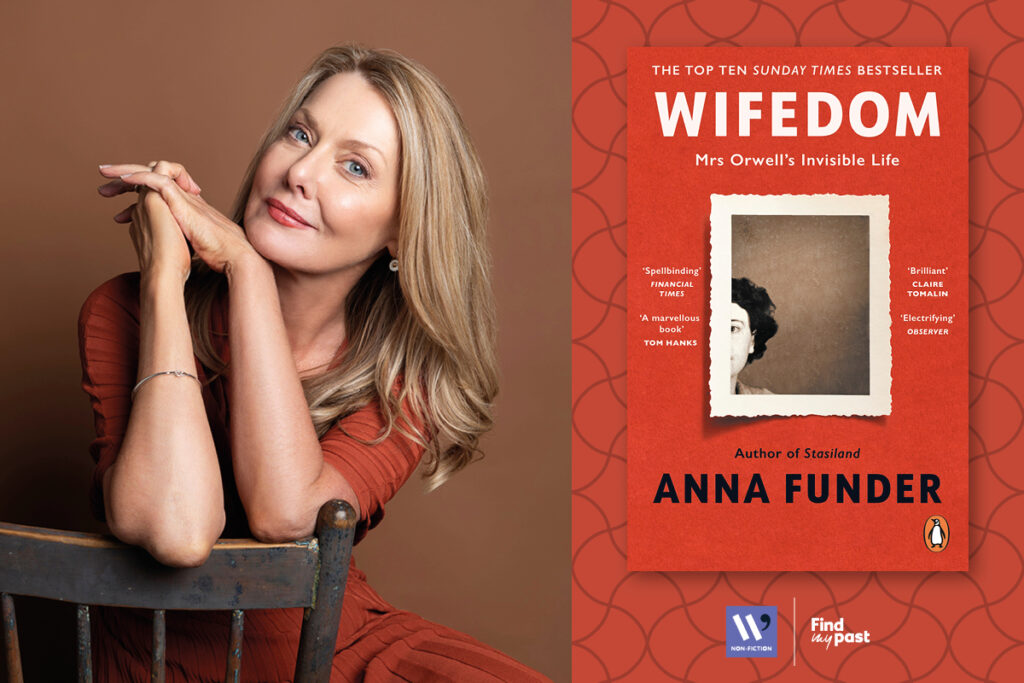

Wifedom: Mrs Orwell’s Invisible Life by Anna Funder offers a breathtakingly intimate view of one of the most important literary marriages of the 20th century.

Longlisted for the 2024 Women’s Prize for Non-Fiction, judge Professor Suzannah Lipscomb had this to say about the book: ‘This wonderful book challenges the way that women are excluded from the dominant narrative. It is intelligently and compellingly written and, in analysis and delivery, is both original and revelatory.’

To find out more about the book we spoke to Anna about her writing, research and current reads.

Describe your book in one sentence as if you were telling a friend.

Wifedom is about Eileen O’Shaughnessy, George Orwell’s brilliant first wife, who saved his life and worked closely on his books, and it asks the question: just how is it that a woman can be made invisible — first by domesticity, and then by history — and are these sly forces still at work today?

Did you have any revelation moments when writing your book? When the narrative and your objectives all fell into place?

For a long time I was embarrassed that this book took seven years to write. The research was immense, almost overwhelming: to find behind Orwell’s life and work a woman who had been made to disappear – first in life, by him, and then in history, by the biographers. It was like literary or historical detective work and I didn’t know if I would manage to find a form to show both Eileen, and how she’d been erased. I was sometimes afraid. I felt as if I was taking on the norms of our society – the patriarchal ones – and so, possibly, putting myself beyond the pale. But they were what I was up against, because they were what had hidden her.

I wanted to make Eileen live again in the readers’ imagination, as she did in mine. But all I had were some letters, the accounts of a few of her friends and gaps in the record. Eventually, I saw a pattern in the gaps, where she had been ‘passive voiced’ away, where her ideas, courage and work were related without mentioning her: ‘conditions were idyllic’, ‘the manuscript was typed’, ‘the visas were obtained’ or ‘the baby was collected’. It was like doing a brass rubbing: the lines of my narrative appeared from the gaps in the historical record.

I remember where I was — a borrowed beachhouse — when I began to write the first piece of narrative based on Eileen’s letters, from her point of view. It was the scene where Eileen stays in bed for two hours as six Spanish secret policemen turn her hotel room upside down, searching for incriminating material. Orwell, who learned of this from Eileen of course, describes it in his book not as an example of her foresight in giving the manuscript of Homage to Catalonia she’s been typing to her boss for safekeeping, nor of her calm courage in staying in bed and so saving their passports and chequebook, which she’d hidden under the mattress, nor of the terror she must have been living under for many months, in anticipation of exactly this happening. For him, it’s an example of the ‘decency’ of Spanish men. As I started then to write this scene from Eileen’s point of view, I began to understand that I would, after all, be able to write a book that contained two kinds of truths: an emotional one, drawn in scenes using Eileen’s real letters. And a factual one, with, as it turned out, 40 pages of endnotes, to describe what really happened, what Orwell and his biographers omitted, or buried in footnotes, or couldn’t see. I thought in this way I might make Eileen live again in our imaginations and in her own words, as well lay bare the mechanisms of patriarchy by which a woman, even one as remarkable as she, can be erased.

What is the one thing you’d like a reader to take away from reading your book?

Claim your pronoun! Do not say ‘we arranged the Christmas dinner/parent-teacher meeting/holiday/dentist appointment/pest man/saxophone repair/retirement village for dear Dad etc etc.’ Say ‘I’. Self-effacement is traditionally a feminine virtue in patriarchy, but eventually it realises itself and it looks like a crime.

Which other female non-fiction writers inspire you and why? Any particular title?

Oh so many! Woolf, always. A Room of One’s Own in particular, for the humour of it, the compression, and the apparent effortlessness of her writing point of view, which is in fact a standpoint outside of patriarchy, looking at it as if it is odd and irrational, and therefore should be — indeed can be — changed. Adrienne Rich, whose essays are a touchstone in thinking beyond accepted categories of gender, and so, liberating. Maya Angelou’s I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings makes the finest literature of life and truth, and wrings human dignity from the hardest circumstances. I delight in Joan Didion, for her prose style, her cool eye, and the sudden, startling emotional effect she so often elicits. Hannah Arendt has been very important for my work on totalitarianism. Gita Sereny, for the painstaking, non-judgmental way she looks for accountability in Albert Speer : His Battle with Truth. Simone de Beauvoir, The Second Sex – simply monumental. Svetlana Alexievich, most especially Second Hand Time, for showing us the beauty of the quotidian, and making an art that bears witness. Kate Manne, the brilliant young philosopher, especially for her lucid Down Girl.

What is the best piece of writing advice you have ever received?

Leave a hook. At the end of each day, leave dangling a sentence, or the thread of an idea so you can grasp it the next day, and go on. It’s a trick to tame the terror of the blank page. It works!

What book is currently on your nightstand?

Clare Carlisle’s The Marriage Question, Amia Srinivasan’s The Right to Sex, Jenny Erpenbeck’s Kairos, Jesmyn Ward’s Let Us Descend, Claire Keegan’s So Late in the Day. I just finished Hilary Mantel’s A Memoir of My Former Self, which includes her extraordinary Reith Lectures on writing historical fiction, and what we owe the truth. It’s still there because I want immediately to reread its dogeared pages. I generally have some Auden poems on hand on the shelf underneath, to remind me how seemingly simple language can wring your heart.