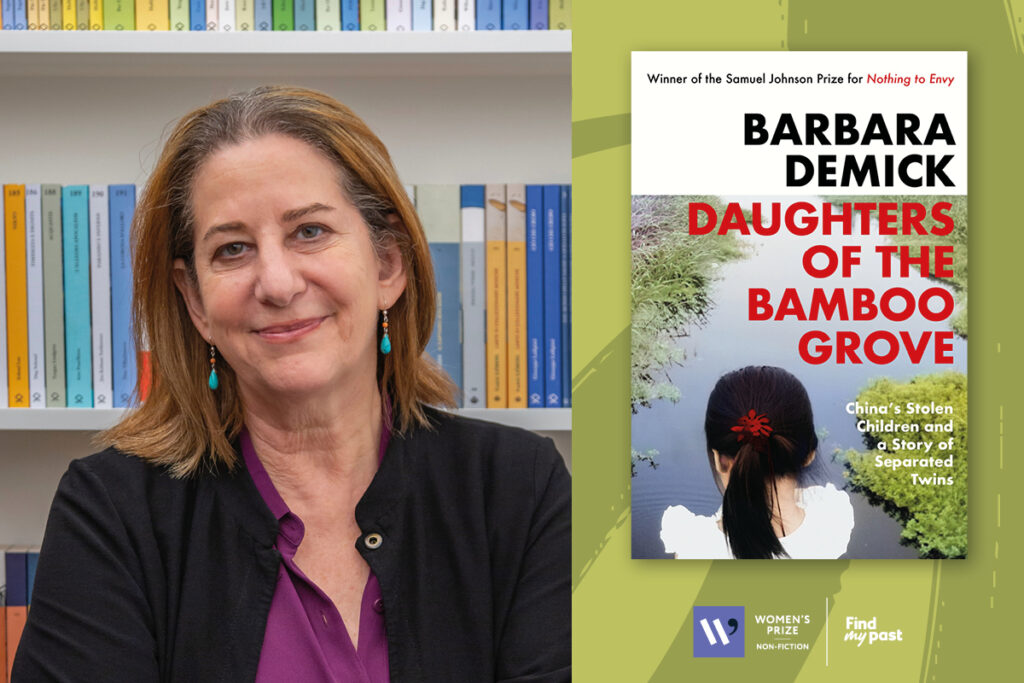

In Daughters of the Bamboo Grove, award-winning journalist Barbara Demick combines intimate storytelling with investigative reporting to reveal how China’s one-child policy led to the trafficking and international adoption of children, told through the powerful true account of separated twins.

Longlisted for the 2026 Women’s Prize for Non-Fiction, judge Nicola Elliott said: “I absolutely loved Daughters of the Bamboo Grove – it tells the extraordinary story of Americans adopting children through China at the time of China’s brutal one-child policy, told through the eyes of twins. It left a deep impression on me.”

To learn more about the book we spoke to Barbara about her writing process, inspirations and more.

Congratulations on being longlisted for the 2026 Women’s Prize for Non-Fiction; how does it feel to be longlisted and what does it mean to you?

Daughters of the Bamboo Grove is a book written by a woman (myself) about women and dedicated to women trying to discover their identity. This award feels special to me, more so than other accolades I’ve sought over the years because it is weighted with meaning about themes close to my heart.

How would you describe your book to a new reader?

This is a true story about identical twins, one Chinese and one American, and how they were separated and reunited. I discovered this tragedy in 2009 while reporting in the Chinese countryside on impoverished families whose babies were taken away because they couldn’t pay the fines for violating China’s notorious one-child policy. The family at the centre of the drama had twin girls, one of whom was seized and placed into the lucrative adoption market. The family asked for my help. I tracked down the stolen twin in Texas, where she had been adopted by evangelical Christians. Years later, when the girl turned 18, I travelled with her back to China to meet her identical twin and the rest of her family.

What inspired you to write your book?

It is easy for outsiders to demonize the Chinese. I wanted readers to understand why hundreds of thousands of Chinese babies, mostly female, were given up in the late 20th and early 21st centuries. Those of us raised in democratic countries couldn’t grasp the level of coercion applied by the Chinese government to enforce the one-child policy. The prevailing narrative was that the heartless birthparents discarded their girls like unwanted kittens because they valued only boys. This scenario has been very destructive psychologically to adoptees who have high rates of depression and suicide. That’s why I decided to dedicate my book to adoptees with the hope it will help them understand where they came from and how they got to where they are today.

What did the writing process, from gathering ideas to finishing your book, look like?

Unlike most books about adoption, focusing on adoptive families, this one started in China. I travelled to some of the most remote reaches of China, villages rarely if ever visited by a foreigner, no less a journalist. I had to hike up goat paths and to cross a stream on fallen trees to reach these places. Villagers were poor, marginally literate, vulnerable to exploitation by government officials. I wrote these stories for the Los Angeles Times in 2009. But the book had a long gestation. It was that same year, 2009, that I first met a nine-year-old girl who told me that her identical twin had been abducted as a toddler by government officials. Although her Chinese family didn’t know she had been trafficked for adoption, I suspected as much. I was able to locate the missing twin as an adoptee in Texas through adoption chat groups on social media. It would have been unethical to publish anything exposing a young child. But years later, the adoptive family in Texas reached out asking for my help connecting the girl, now a teenager, with her twin sister. One thing led to another and we decided together the story should be told. The adoptee, Esther and her American families, traveled with me to her home village over Lunar New Year in 2019, a full decade after I discovered this story. The reunion was magical. I had intended to return to China the following year to wrap up the reporting, but the COVID pandemic shut everything down. By the time China reopened, I had already published a book about Tibetans (Eat the Buddha) and it seemed too dangerous for me to visit China. Some of the final reporting had to be done by telephone and video chat.

How did you go about researching your book? What resources or support did you find the most helpful?

Daughters of the Bamboo Grove is an oral history. Most of it comes out of my own original reporting. I also had help from a very courageous Chinese journalist who had been reporting for years, but was unable to publish initially because of government censorship. He was very generous in sharing government documents he gathered. (He is credited throughout the book). Adoptive families in the United States opened up about their experiences. I also read academic studies about Chinese demographics and economics, looking at the changing status of women at the cusp of the 21st century. I was also intrigued by scholarly writing about identical twins and how those raised apart – like these twins, one Chinese and one American – were the key to untangling the age-old questions of nature and nurture. I was fascinated by the twins and how their identities were shaped by their culture.

Which female non-fiction author would you say has impacted your work the most?

Jung Chang. I read Wild Swans long before I ever thought of moving to China. Her approach to a multi-generational autobiography inspired my own writings about Chinese families.

What is the one thing you’d like a reader to take away from reading your book? If applicable, is there one fact from the book that you think will stick with readers?

Several readers mentioned to me they were impressed that I referred to the shameful history infanticide and child abandonment outside of Asia. Scholars have estimated that up to 40 percent of babies were abandoned in 18th and 19th century Europe. Jean-Jacque Rousseau disclosed in his Confessions that he had dumped three of his own children in a foundling home, where they most likely died.

Why do you feel it is important to celebrate non-fiction writing?

Reality is more important than make-believe. Not that I don’t love fiction, but non-fiction is urgent at a time when political manipulation, social media and AI leave readers struggling to discern the truth. There is something very powerful about telling a story with a stamp of authenticity. When you can say, none of this is made up.

Daughters of the Bamboo Grove: China’s Stolen Children and a Story of Separated Twins

by Barbara Demick

Find out more