Ahead of the publication of her memoir, Possessions, writer Davina Quinlivan explores what imaginative memoir means to her and why it appeals.

My ancestors imagine falling through clouds and dancing on the rooftops of the tea houses near the golden pagodas, but the sky is the wrong colour, like a weird neon blue. The trees are different too. One of them looks like a Burmese nat, a tree spirit. Closer, it looks like someone they’ve seen before. They think it looks like me. ‘Are you her?’, they ask. ‘The one who belongs to us?’ The tree is covered in oakmoss and amber-coloured sap from willows and elders – English trees. They take out an immaculately wrapped Tunnock’s Teacake: an offering to the tree who was also, they believed, a great forest guardian.

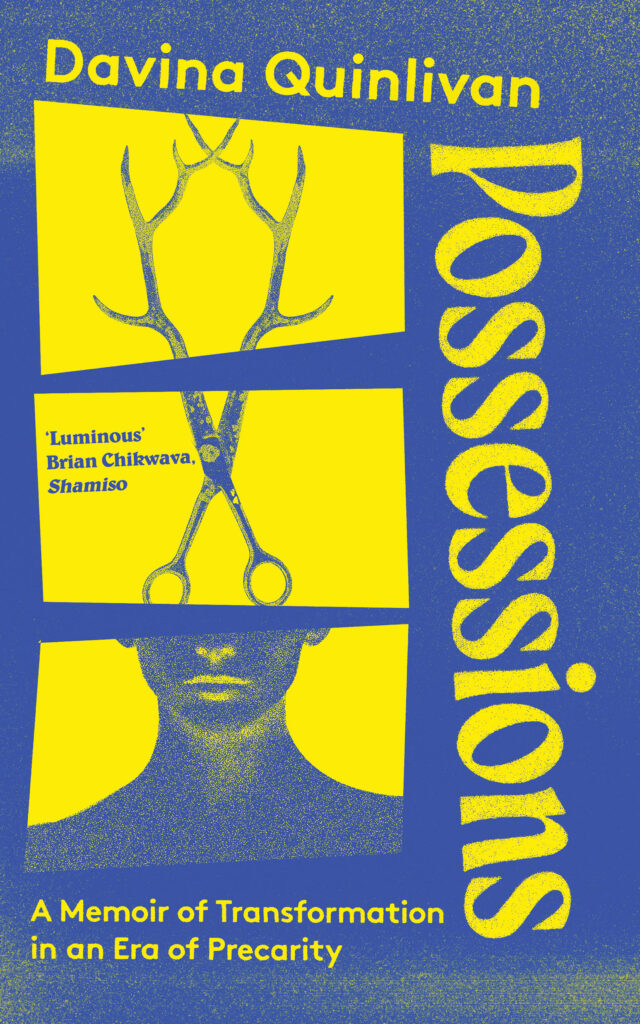

‘Imaginative Memoir’ is perhaps the best way to describe my writing in Possessions: A Memoir of Transformation in an Era of Precarity. Put simply, I write memoir inspired by lived experience, but I tend to ‘world-build’ inside the life-writing, which is to say that the stark realities I write about often have a magical-realist edge or dream-like ‘threshold’ mirroring another reality: a window on to an alternate world with a deep, transformative power. I want to be clear and admit that this was never the plan and I had no idea it would be the way for me, but I am absolutely sure it is right and that feeling is bone-deep. It’s what I do.

The energy of the writing pulses through me, it gives me great relief in being able to open that threshold, to trespass between the real and unreal, to blow the doors off reality as well as to do justice to it, to my perception of how things really are, which is filled with strangeness and time tipping sideways, bits and bobs going bump in the night. Isn’t that how we all live, really? There is no ‘line break’ between the dead and the living, the ancient and the new, the body and the soul. At least, there isn’t for me. Time and space collapses and everything I experience co-exists within me, one way or another. I’m in my bedroom, but I can hear the chiming bones of the bodies under the Bronze Age burial ground, which lies just north of my garden gate – a flicker of feeling still quenching the earth, breathing within the radiating rhythms of birdsong, the miniature scaffold of spider webs at my bedroom window’s ledge.

I grew up in Hayes, a bustling suburb close to Heathrow airport. My parents arrived in 1950s England as teenagers newly ‘exiled’ from Colonial Burma and India. My father worked as a warehouse security manager and my mother was a dinner lady at my local primary school. They are long gone, but I still carry their memory with me as I write from my home in rural England, the place they might have dreamed of as children growing up as citizens of the British Empire. Out here, on the farmland, it’s all gone a bit Pre-Raphaelite. In my mouth and in my throat, this green and pleasant glowing land. I count all the stained glass images of English trees in early Christian churches, luminous in their own sacred language of reverence for nature. In my dreams, their light splutters and sparkles behind my retinas, electrifying my bedsheet-bundled, sleeping soul.

My ancestors were European Colonials who married women from Burmese tribes; they appear in my writing as an ambiguous presence: all at once greedy, loving, scowling, child-like and mischievous, at times. These goblin ancestors arrive in the text like levelling tools, my very own ‘spirit-levels’, helping me to understand where the land lies, to be present and clear-eyed, to articulate emotions and, often, to help me express something funny or sublime, ineffable without their ‘bopping heads’ appearing in the trees or the undergrowth near my home. However, it is not only these goblins who appear in the book. I’ve enlisted a whole cast of mythic, folkloric or surrealist images involving Saint Sidwella (the Patron Saint of Exeter), Joni Mitchell, a dungaree-wearing witch in a cave that is also a ‘zoom’ interview, Salvador Dali’s melting clockfaces, a mystical portal that is also a ring, an origami swan, the head of Saint John the Baptist, floating scissors and a hologram, Burmese cat.

Possessions is about shape-shifting through all the changes, namely my experiences within Higher Education. It’s the journey towards the realisation of what the pursuit of knowledge can truly be, if only I could be brave enough to rid myself of all the fears and conditions I associated with assimilation, inherited trauma, the inequalities of the class system and the spectre of Empire. These things possessed me, but I had to let them go. I love teaching and learning, I always have, but it has been quite a ride over the course of 20 years; motherhood; mourning the loss of most of my family; witnessing the world changing as I taught online and heard the sheep call out in the fields beyond my window. I being pushed out of my body and into the metaverse. The book is about taking control of reality and blowing the doors off it – a radical, deeply political and urgent form of action, a fictional activism, if you will, which is also a kind of ‘spirit-level’, a corrective to all the de-centering. A Burmese cat slinking through a cave filled with watery light. A beheaded saint calling me back out to the fields, to witness the floods and the changing of the seasons.

Davina Quinlivan’s latest book is Possessions: A Memoir of Transformation in an Era of Precarity (September Publishing, 29 January)