The 2019 Women’s Prize for Fiction winner will be announced tonight, and ahead of the big reveal we asked six well-known celebrity faces to review each book on this year’s shortlist. Read on to find out what Viv Groskop, Scarlett Curtis, Naga Munchetty, Melanie Sykes, Debbie Wosskow and Paula Hawkins thought of this year’s shortlisted books.

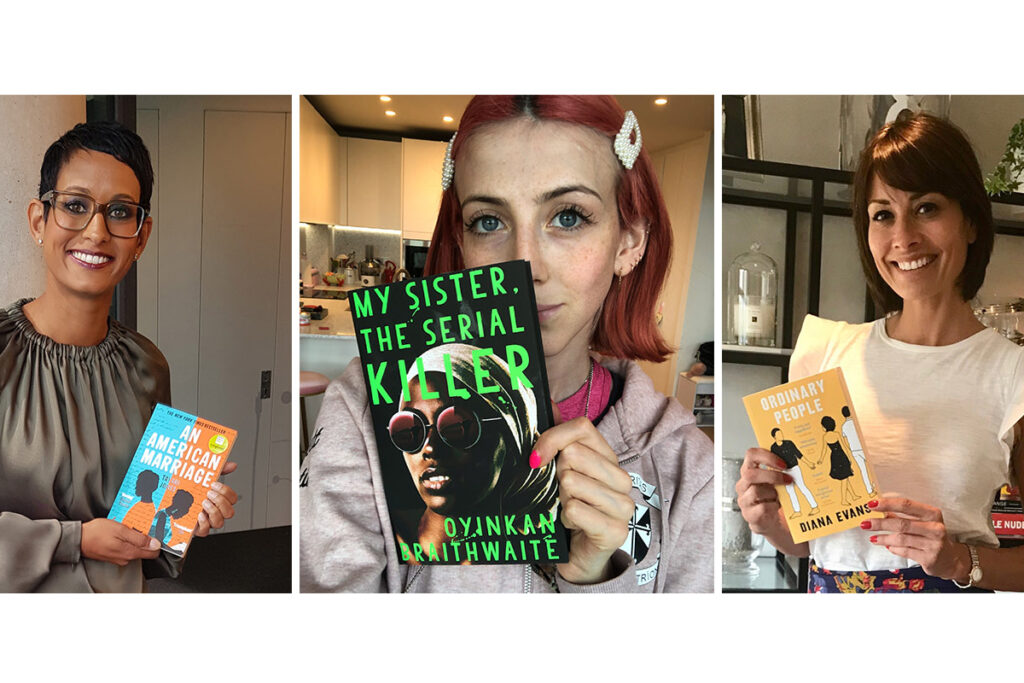

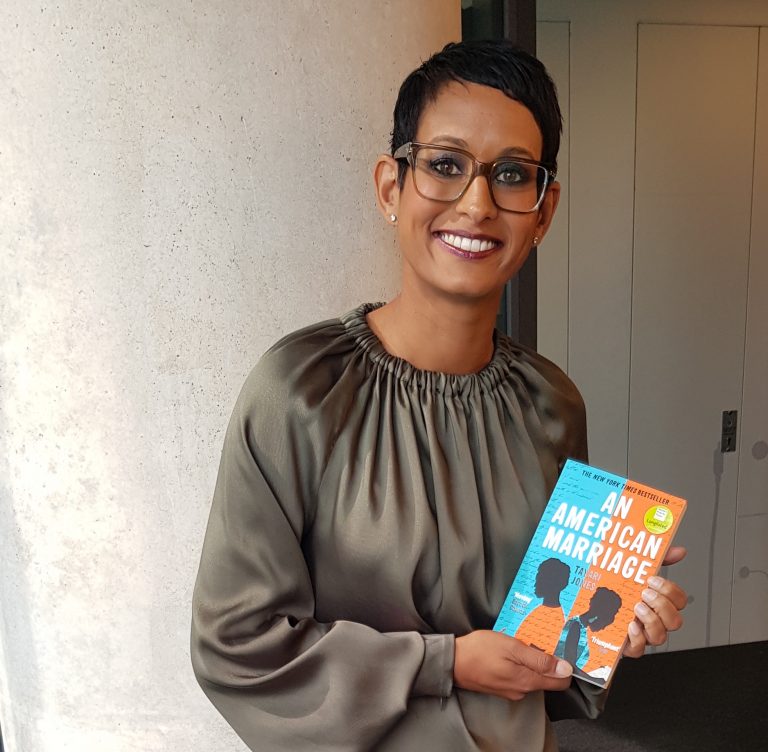

Naga Munchetty, TV presenter

An American Marriage by Tayari Jones

How do you know if you’ve made the right decision when you commit to marriage? You don’t. It’s a risk. A gamble. And at times marriage will be difficult.

So when Celestial and Roy, a couple you are never quite sure should be together, or if they will make it, are torn apart through a miscarriage of justice and by being the wrong race, at the wrong time – It’s easier to think that this is the start of the end.

This book is by no means that simple. Loyalty, duty, family, secrets and anger are gently, yet powerfully woven through every page. As the pair analyse their own story, the reader is given a sense of intimacy that is a rare gift from an author. Emotions are precariously balanced as the Black-American characters battle the typical fallout from a marriage in trouble, all with the extra pressure of racism, prejudice and a gross lack of justice.

It is more than about the incident – that in itself is incidental, this is about how marriage and relationships are messy and painful. As a reader, this is keenly felt.

The use of different narrators is a device that works well – Tayari Jones keeps the story moving yet uses different perspectives to build layers with a breadth of emotions. That’s probably why I felt no loyalty or favouritism to any character, yet it was impossible not to empathise with them all.

This tale is quietly told, yet with loud moments and glaring modern-societal problems clearly laid out. The history of slavery clearly weighs on the modern couple – When a black-American baby is referred to by a white child as a “baby maid”. One phrase that stuck with me was when Roy repeatedly refers to the fact that they were living a “Huxtable” life – something that is clearly not sustainable in modern America.

Celestial’s constant battle to be left to make her own decisions is poignant – Her family brought up to know her own mind yet only if that fits with their idea of what is socially acceptable – will resonate with many women, yet alone Black women.

As a former judge for this prize, I am certain that this would also have made my shortlist. I was gripped from the start and to the very end. By no means did I fall in love with any character, I’m not sure I even liked any of them, but it was a joy to see their lives unfold.

Don’t expect a cathartic ending or even a satisfying one, but this simply reflects the characters and the impossible situation they are in. This book does, however, leave a mark – very few have done that for me before. The delight of being party to a fictional marriage that is so reflective of real live is uncomfortable. Insightfully so on Tayari Jones’ part.

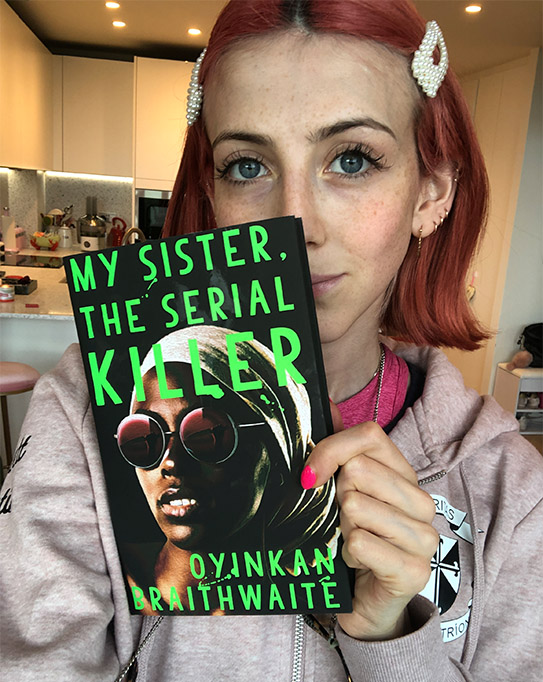

Scarlett Curtis, Feminist Activist

My Sister, the Serial Killer by Oyinkan Braithwaite

I remember once being told by a friend that I would be the first person they would call if they murdered someone and needed help to dispose of the body! Amid a worried analysis of what it is in my nature that seems to scream ‘silent accomplice’, I have often wondered that were that call ever to come, how long would it take me to grab a bottle of bleach and walk out of the door?

My Sister, the Serial Killer is the breath-taking debut novel by 32-year-old Oyinkan Braithwaite. Set against the backdrop of Lagos, Nigeria, the story follows Ayoola (the serial killer) and Korede (the sister). Over an un-put-down-able 240 pages, Braithwaite draws a portrait of two vastly different and endlessly fascinating young women. Korede, who narrates the novel, is a nurse; dutiful, quiet and solemn, a woman moulded by a lifetime of feeling less beautiful than her sister and a violent childhood which is slowly revolted throughout the novel. Her sister Ayoola is beautiful, vibrant and alluring with an hourglass figure and a tendency to kill her boyfriends.

At the heart of this novel is an examination of the impact of trauma and abuse on the female psyche. Braithwaite uses Korede and Ayoola to break down the ways in which violence begets violence at the same time as illustrating the unbreakable ties that blood and shared experience create. The result is a novel that is wickedly dark, delightfully witty and radically important.

The power of female anti-heroes is their ability to give the reader a chance to explore the darker spaces of her own psyche. By placing two women at the centre of each of the (many) crimes that take place within this story, My Sister the Serial Killer allows its reader to reflect on their own capacity for deception and violence. Luckily, I tend to, like most of us, think of myself as a ‘good person’ and murder currently feels out of my wheelhouse!

Mel Sykes, TV and radio presenter

Ordinary People by Diana Evans

In Ordinary People, the two couples Melissa and Michael and their friends Damian and Stephanie, are held hostage to a domesticity they didn’t sign up for. Now parents, baby groups, ball pools and the mind-numbing boredom of early motherhood are explored along with gender, race and politics. This book beautifully evokes the death of passion, killed off by the monotony of routine, as the couples mourn the passing of their former lives. Diane Evans cleverly performs open heart surgery on two contrasting marriages in a way that feels like emotional butchery. Her words lift you up and throw you against rocks to the sound track of John Legend’s ‘Get lifted’ album (hence the title) which brings another level of richness to the story.

Although Ordinary People has some very funny moments, it rekindled a personal time for me with such accuracy it was really rather painful.

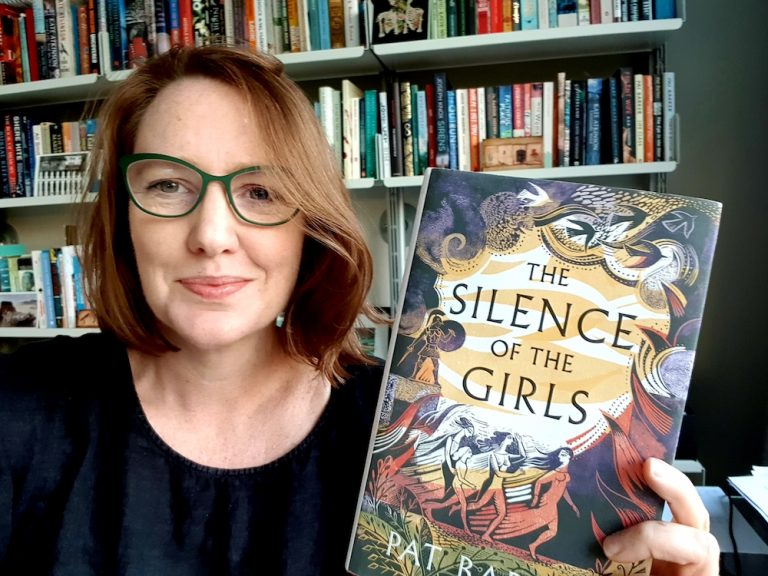

Paula Hawkins, author

The Silence of the Girls by Pat Barker

The Silence of the Girls is The Iliad as you have never read it before, told from the point of view not of the victors, or even of the conquered army, but of the spoils of war – the women. Pat Barker’s stealthily powerful novel gives a voice to Briseis, the nineteen-year-old Queen of Lyrnessus awarded to Achilles (known in this account as neither godlike nor great, but as a “a butcher”) as a prize for his feats in battle.

Barker is unflinching in her account of the horrors of war, of rape camps and retributive murders, and yet her quiet anger is skilfully shot through with humour. For all its terrible subject matter, one of the striking strengths of this book is how immediate Barker renders ancient history: the women at the heart of the story speak plainly, and if there are anachronisms – such as the rugby songs sung by triumphant soldiers – these are intentional, bringing us closer to the action so that it is not, in Briseis’ own words “unimaginably distant”.

Towards the end of the novel, Achilles has his say, a chance not exactly to redeem himself, but to reveal a thoughtfulness his ‘butcher’ reputation belies; but this remains very much the women’s story. In retelling this tale the way she does, Barker urges us to reconsider the way we tell all our stories, all our histories, those we put at the centre of them, and those we consign to supporting roles.

Viv Groskop, comedian and author

Circe by Madeline Miller

If you told me I’d fall in love with a novel about a woman who tells you in the first sentence that she is a nymph, then I wouldn’t have believed you. Fortunately I had read — and loved — Madeline Miller’s last novel Song of Achilles. She has a richly deserved reputation for retelling the Greek myths in a way that is completely engaging and refreshing, whether you know much about the original myths or not. (And I’m afraid I’m a bit of a slouch in that department.)

Miller draws you into a story that is so intimate that it feels almost like a memoir. This is Odysseus’ world seen from Circe’s point of view and in her own words, always with a discreet side-eye of the modern messages we might draw about Circe being “the first witch.” She’s best known, of course, as being the one who turned Odysseus’ men into swine.

From birth it is clear that Circe possesses an intimidating power different to that of the other gods: witchcraft. This makes her suspect and she is banished to an island for millennia where she hones her potions and befriends wolves and lions. The novel explores her motivations, her inner monologue and the true nature of her relationship with Odysseus, transforming her from a minor character into someone at the heart of the myth.

It’s an unusual and beautifully written novel that redefines what we expect from a first-person narrator. The expression “We are the daughters of the witches they couldn’t burn” kept echoing in my mind as I was reading this.” Circe started it. And this is the mother of all reads. It has the added bonus of making you feel very clever afterwards, especially if you couldn’t really explain who Odysseus was to start with.

Debbie Wosskow, Entrepreneur and Co-Founder of AllBright

Milkman by Anna Burns

What remains to be said about ‘Milkman’? Winner of the Man Booker Prize. Challenging. Long sentences. Few paragraphs. Already compared to a difficulty level of reading ‘articles in the Journal of Philosophy’ by one critic. Take that reader…

The story takes place in an unnamed town in an unnamed country, although this appears to be the author’s native Belfast during the 1970’s troubles. England is referred to only as ‘the country over the water’. The book is dreamlike, strange and complex. The plot is compressed into the first sentence: ‘The day Somebody McSomebody put a gun to my breast and called me a cat and threatened to shoot me was the same day the milkman died’. The voice of the novel belongs to ‘middle sister’ – who wanders her local street reading 19th century novels, with a Father dead after a struggle with depression, and her Mother ‘one of the Top Five pious women of the district’. Harassed by a 41-year-old paramilitary officer nicknamed the Milkman – the kernel of the story is a Me Too tale. Middle sister’s community, indeed, even her family, assume she is to blame for enticing the milkman away from his wife.

So far, so grim. But the balance to this dark predicament is the wit of the narrator. She is mocking in her patter – of her town’s gossip, hypocrisy and toxic sexism. Middle sister dares up to keep up and to follow. She is a survivor, when surviving is a miracle. She is courageous. Buckle up for ‘Milkman’. It’s original and funny and intriguing. I loved it.