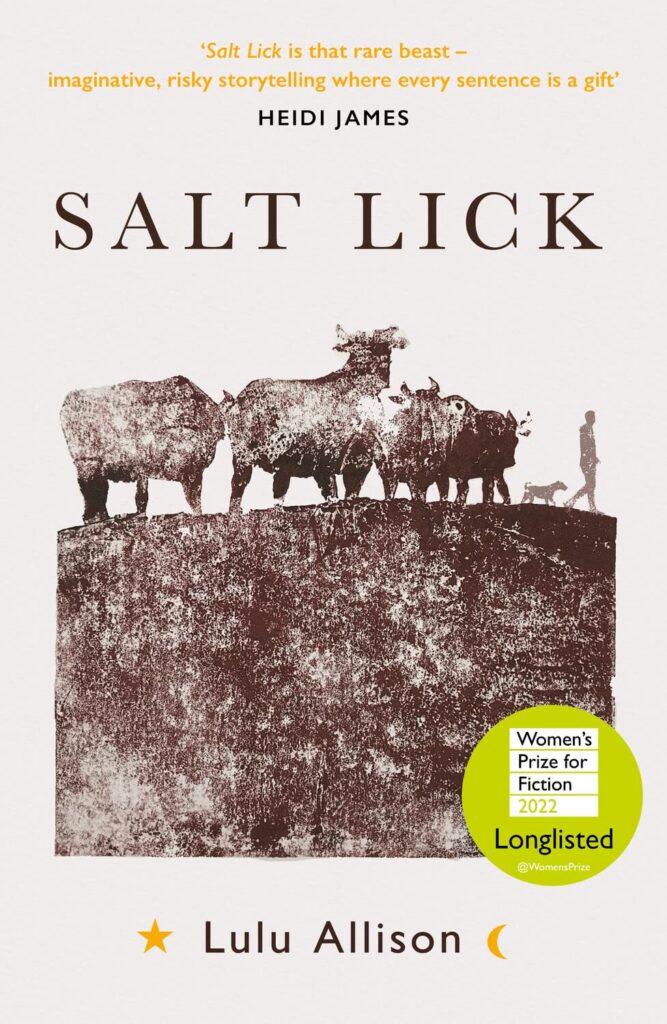

Meet Lulu Allison, author of the Women’s Prize 2022 longlisted novel Salt Lick.

Author Heidi James said ‘Salt Lick is that rare beast – imaginative, risky storytelling where every sentence is a gift’.

Risky storytelling is an intriguing concept, so what was the inspiration behind the novel? We grabbed a quick five minutes with each of the authors behind the longlisted books to ask that question and more…

Describe in three words how it feels to be longlisted for the 2022 Women’s Prize for Fiction.

Wildly thrilled, lucky

What inspired you to write Salt Lick?

Three things inspired me:

A stray thought of a man in prison, imagining the interior of his body as a place of escape.

My fears of a populist and rightward-turning world.

A song called ‘Peace in the Valley Once Again’ by alt-country duo The Handsome Family; it describes nature reclaiming a shopping mall and is a song I find profoundly comforting.

Can you describe Salt Lick in one sentence?

Set in a near-future England, where people live in cities and the countryside is once again wild, Salt Lick is about the necessary hopes and loves of individuals in a world that has slipped, further than we are now, down the wrong road.

Are there any locations that have a special connection for the book?

I wanted to include a landscape that might be changed by future sea-level rises so it is set in Suffolk. I spent some happy days bumbling around the Southwold area, enjoying the brown North Sea and biscuity beaches, birch woods, pints of Adnam’s bitter and noticing features I later drew on to re-invent for the book.

And the A12, a motorway in the future, no longer used by cars, overrun by groundsel, bramble and bindweed.

What was the first thing you ever wrote?

If you mean when writing was the end in itself, it was an art project from 2013, when I still didn’t know I wanted to be a writer. As an artist, I began a blog called Shades. I had been struck by the different UK media response to the deaths resulting from the Boston marathon bombing and the relentless daily death tolls from Iraq and Afghanistan. We were invited, with so much detail, to mourn the former, where as victims of the two wars were only ever noted as a tally. As a way to think about how to properly grieve for distant and ignored casualties, I wrote imaginary portrait sketches for each counted in small headlines such as Seven Killed by Marketplace Bomb.

Why did you become a writer?

Writing for the project above, I realised I had found what I should have been doing all along. I learned that my deep love of books had another iteration. I discovered the chance to think, to deeply explore all the things that fascinate me about both our shared and isolated experiences.