From the Women’s Prize Archives.

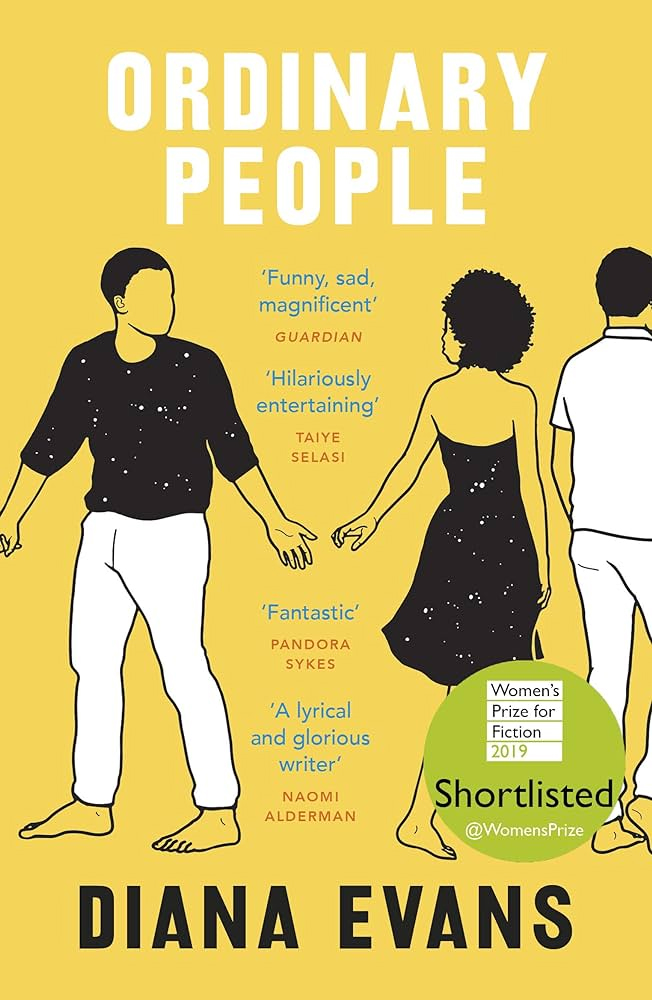

Diana Evans has been shortlisted for the Women’s Prize for Fiction for Ordinary People. We caught up with Diana to ask her about the musical influences within Ordinary People, the themes of marriage and motherhood and Barack Obama and Michael Jackson as opposing bearers of black culture and identity.

Ordinary People is based around two couples struggling to maintain long-term love. Why was this something you wanted to write about?

My primary literary inspirations for broaching the subject were John Updike’s Couples and Richard Yates’s Revolutionary Road, both novels that dissect marriage and long-term domestic love from a male perspective. I wanted to redress the balance and present the story equally from male and female perspectives, in the context of contemporary Black-British middle-class Londoners who I feel lack adequate visibility in our culture. On a personal level, I have observed in my own circle of friends how a lack of honesty about our lives sets in as we get older, as if we’re afraid of showing failure in love and marriage. A frank and clear picture was due, perhaps to make us braver. Literature has a special power that way to free us with the truth.

In your book, you make repeated references to John Legend’s Get Lifted. What is your favourite song from the album and why?

My favourite song on that album is I Can Change. It’s a very funny song, and very visual too. I love the way it argues with itself, plays on its internal doubt about commitment in love. Whenever I listen to it I always have to do Snoop Dogg’s bit with him, especially when he describes the woman John is falling for as ‘off the hizzle’. The hizzles thereafter recur through the rest of the novel as they proved to be an irresistable decoration. Funnily enough, my least favourite song on the album is Ordinary People!

Motherhood and loss of identity are bound together within the book – what motivated you to write about this idea of the female self in flux?

Motherhood can swallow a woman whole. I’ve seen women disappear into their children. I’ve seen them disappear away from each other, losing the refuge of support that other women can provide because they’re afraid to open up, are holding on to themselves so tightly so that something is preserved. That struggle to hold on to the self, the internal embattlement of motherhood, needs ongoing examination, because it is bound up in archaic attitudes towards parenting and domestic life that still pose women as the natural primary carers. I think most men have an inner patriarch that surfaces in the traditional nuclear family and we need to look at that. Women are often dismissed as complainers when expressing their true feelings about motherhood, but these are the expressions of very real, valid, and enduring imbalances in our society.

In the book it seems Michael Jackson is used as the counterpoint to the hope initially embodied by Barack Obama, what do these two figures represent?

They were both drawn upon in the obvious sense as icons of black culture, the election of Obama and the death of Jackson bearing a historical importance that I wanted to document on an intimate level, occurring in the fabric of the lives of individuals. More symbolically, they are opposing bearers of the cruel and stultifying weight of black history, that is, its negative side, the history of exploitation and psychological abuse: the weight on Obama’s shoulders to be everything to everyone, to ‘represent’, to somehow save us, and the weight on Jackson to embody a kind of universal face that he could not inhabit. I was attempting to highlight the sometimes painful complexities of blackness and how our history is entangled in our ordinary experiences, hence Damian drawing profound meaning from Jackson’s death in relation to that of his father.

Which women writers are you most inspired by and why?

One of my first loves was Alice Walker and I continue to be inspired by her magnanimous spirit and wisdom and her insistence on living as wholly her self. I love Bernardine Evaristo’s work for its chutzpah, flamboyance and daring experimentalism. Daphne du Maurier has written some of the best short stories I’ve ever read (such as ‘Monte Verita’), and I also love the short stories of Lucia Berlin, Toni Cade Bambara, Lorrie Moore and Grace Paley. Also Mary Gaitskill does some incredible things with language which I really respect, that luxuriating in the possibilities of words.

What are you working on next?

Another novel. There are at least three more beyond that which I’m dying to write and by my calculations according to my average novel-writing speed I’ll be approaching seventy when I’ve finished them all. I try not to rush. It’s always counterproductive.