From the Women’s Prize Archives.

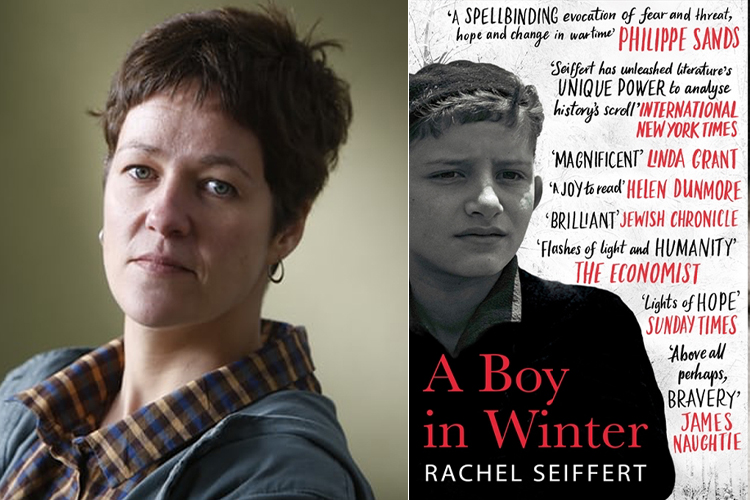

The fantastic Rachel Seiffert has been longlisted for the 2018 Women’s Prize for Fiction for A Boy in Winter. Read on to find out how how Rachel has been influenced by both Joseph Roth and Toni Morrison and why the considered explorations of human experience in a novel are more vital than ever in our turbulent political times.

Do any of the experiences you describe in the novel reflect actual accounts of the time?

I was writing another novel entirely when I was captivated by an account from a German engineer (Willi Ahrem) about his experience of being stationed in the Ukraine during the second world war; the events in the novel are based on his account combined with others I found in my resulting research. He was an anti-Nazi, couldn’t countenance fighting for Hitler, and had avoided the draft by using his engineering qualifications to be stationed behind the lines on a road-building project. However, it was exactly in such behind-the lines places under German occupation that the Holocaust was perpetrated. So, this man who had done all he could to avoid a war he considered criminal found himself witness to an even greater crime unfolding. It was this moral dilemma which caught me – would you risk yourself for others? How do you respond when presented with the unthinkable? The question was as applicable in its own way to all my characters, German, Ukrainian, Jewish. These were all humans at the sharp end of history – the way humans act under duress is often most revealing.

You conjure the backdrop of wartime Ukraine so immersively. What research did you do to enable you to do this?

Lots of reading – first hand accounts, histories; Wendy Lower & Karel Berkhoff are my historian heroes of the Ukraine during this period, and I am hugely indebted to them. The physical environment was so important to the children’s flight and the engineer’s relationship to the place he was stationed, so I consulted the picture archive at the Imperial War Museum, but I was also very influenced by Joseph Roth, both his reportage and novels, especially The Radetsky March, which is partly set in the same marshy landscape. I had read it years before, but his descriptions of the cavalry training and patrolling in that mud, it’s dispiriting effect, was so memorable, I think that’s partly why I could see Willi Ahrem’s dilemma so clearly, even when I first read his account, because I already had Roth’s images to form a backdrop. In his reportage, Roth also wrote very evocatively about those small towns on the Steppe and their Jewish communities in the early 20th century, so I re-read his accounts to help create the town in my novel.

Which writers do you think have influenced your writing most?

Joseph Roth – evidently! He writes about human frailty so well, with such acuity and understanding – he gets you to love his characters, even as he nails them. Toni Morrison is also an abiding favourite; her insistence that writing should be both political and beautiful is something I aspire to.

In your essay for the Guardian last year, you asked: ‘How does it feel to be on the wrong side of history?’ Was this an important thing for you to explore, given the times we’re living through now?

Yes, absolutely. The politics of consensus, of the middle ground, is failing at the moment, across the globe. People are dissatisfied with the status quo and are turning to the right and left for answers; my familiy lived through just such a time in Germany and I am profoundly uncomfortable with extremes. But as well as becoming more polarised politically, we’re also living in a time of hyperbole; we think and talk and read in extremes – from book & film reviews to Facebook posts and news reports, everything must be described as the best, worst, most, least. It’s divisive; where we should have discussions we often end up with confrontations – unnecessary, counter-productive, all in the name of ‘entertainment’. It’s also so vacuous. I’d like to call a moratorium on superlatives – they rarely describe anything accurately. Very frustrating!

I don’t think novels can change the world, or change people’s minds necessarily, but they can give space for nuance, for more considered explorations of human experience. This kind of engagement feels very important at the moment.

Can you tell us what you’re working on next?

I’m at the very early stages of what I think will be a novel set in the Caribbean in the 1600s – during England’s first forays into empire. It’s a love story, but it’s also about the idea of the New World, and of owning and being owned. The characters I have so far are indentured servants who come out from England in the hope of a new life, but the New World being created is in some ways worse than the old one they left behind.