From the Women’s Prize Archives.

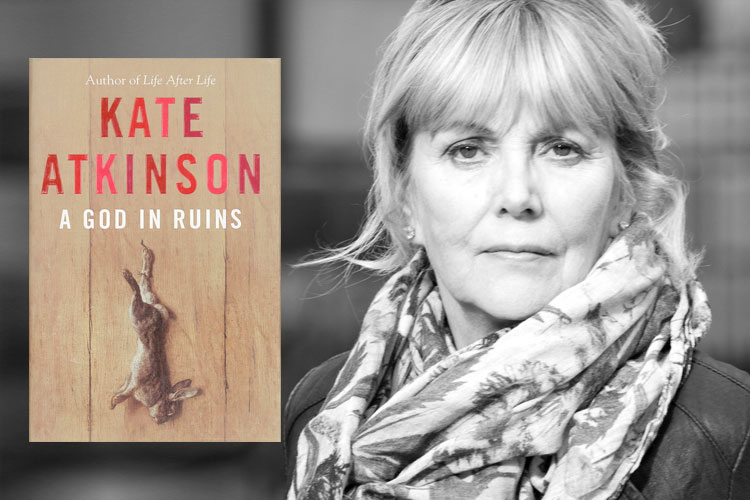

We caught up with 2016 Baileys Women’s Prize for Fiction longlisted author Kate Atkinson, ahead of next week’s shortlist announcement, to discuss her longlisted book A God in Ruins. Read on to find out why Kate decided to return to the theme of World War II in this novel, her research into RAF squadrons and why it’s dangerous to associate authors too much with their work.

What led you to revisit the theme of World War II in this novel after the unforgettable Life After Life?

I knew that I would not be able to cover in one novel the two aspects of the Second World War that interested me most – the Blitz and the bombing campaign. They were two disparate but connected things – the experiences of being bombed and the reality of being the one who drops the bombs. The former is central to Life After Life and the latter to A God in Ruins. The two novels do share some themes and characters but their intention and their execution are very different.

If you asked me if there was one theme above all others in A God in Ruins I would say that it was about our desire for Utopia and our unremitting failure to bring it about.

Although Bomber Command occupies a central position in A God in Ruins, it is also about history and the consequences of actions, both personal and public and how that resonates through time. Time is a big part of much of my writing. I think an obsession with time is related to the fluidity and elasticity of fiction – fiction doesn’t – or doesn’t have to – obey the rules of physics and our ‘real’ lives.

Why did you choose to tell Teddy’s life story, as the focus of this novel?

While the Blitz is the black heart of Life after Life, Teddy is the golden heart of it. He is the emotional touchstone. Often I write a novel and I think, I could do more with that character – like Tracy in Started Early Took My Dog – or Reggie in When Will There Be Good News? As a rule, I’ve not been able to develop them further, but it is interesting (to me, anyway) that Teddy was the character I felt compelled to take into another life, another future too. I loved him too much to let him go. Teddy is at his very best in the war, the most alive he will ever be.

How much research did you do for A God in Ruins?

I did a lot of research about the war for Life After Life so that when I came to start A God In Ruins, much of the ‘groundwork’ had been done in that I felt very familiar with the ambience of the period. The research for the second book was more technical – about the Halifax themselves and the specifics of a bombing mission. I read a lot of biographies of air crew, not just the memoirs of pilots but of all the various crew members to try and understand what it was like to be cramped inside that freezing cold tube of metal, not to mention the constant threat of being blown from the sky or succumbing to mechanical failure. One of the most valuable contributions to my understanding was a tour of a Halifax given to me by the Yorkshire Air Museum at Elvington. Elvington was one of the many squadron bases situated in Yorkshire during the war. My own Canadian uncle served there as ground crew for part of the war (and scooped up my aunt as a war bride and took her home with him.)

The National Archives at Kew are a repository for many of the RAF squadrons’ operational logs and I based much of Teddy’s war on the records of 76 Squadron. There was nothing sadder, I found, than to read the dry sentence that an aircraft failed to return ‘and has therefore been reported as missing’. The casualty rate amongst bombing crews was extraordinarily high, the odds always fixed against those young men. It must have presented a great challenge to go to breakfast the next morning and see so many missing faces, although in truth there was little time (and very little point in) dwelling on the losses.

How much inspiration did you find in the personal stories of the bomber pilots and aircrew?

Those that went through the relentless ordeal talked very little about it afterwards. I admire that reticence but it has robbed us today of much understanding of what their experiences. Now, as that generation approaches its end those experiences are slipping even further from view. Fiction is a (rather poor) attempt at facsimile. The imagination is an act of rescue but by necessity it must render fact through its own lens.

Writing can help to capture the lives of others now lost (although I don’t feel I have any kind of duty as a writer, the joy of art is in its lack of constraint) but writing, all art really, is a form of rescue.

There is so much emotion in this novel, one can’t help feeling that it has to come out of your personal experience. Is that true?

People often ask how much of myself is in a book. Generally I say all of me and none of me. It’s dangerous to associate authors with their work. It’s fiction but the more you are engaged with your writing the more the readers are also involved. I think a reader needs the author to be invested wholly in the writing, otherwise it feels a bit like cheating, in a way.

I tend to get emotional towards the end of writing a book, because so much is coming together and the story feels as though it is going to work and do what I wanted it to do. I love endings – beginnings and endings are what I like most in fiction. The end of ‘A God In Ruins’ for me was the most meaningful and powerful of all the books I’ve written.