Our host Vick Hope is joined by award-winning broadcaster and presenter Kavita Puri.

Kavita is the creator, writer and presenter of the Three Million podcast on BBC Sounds, which won the Gold for Best New Podcast at the British Podcast Awards 2024, and the accompanying book – a “groundbreaking” investigation of the 1943 Bengal famine – is set to publish in 2026. Her Radio 4 docu-series Three Pounds in My Pocket is currently on its fifth season and has been described as “captivating and epic” by The Guardian. Kavita is also the author of the critically acclaimed book “Partition Voices: Untold British Stories”, which has been adapted for stage at the Donmar Warehouse.

Kavita is the chair of the 2025 Women’s Prize for Non-Fiction Judging panel. Listen to the full episode here and read on to see Kavita’s top five most influential books written by women.

I actually wrote to Elif afterwards to say that I can’t believe how this book really spoke to me, and what I realised is it of course is a book about partition – but it’s about war, and it’s about trauma, and it’s about how people process that. And what you pass on to the next generation, knowingly or unknowingly, and how you might not want to tell them and burden them about what you went through to protect them. But in those silences, and in those absences, they know that and they feel it.

I came to Elizabeth Strout late, and I was literally in a bookshop… the guy said “Have you read Olive Kitteridge?” and I thought “No… that’s a funny title for a book!” – I read it and I loved it and then I read everything that she has written. And if we’re talking about Olive, she is complicated and fragile and feisty and she’s a pain and embarrassing and her marriage is kind of messy and she argues with her son – but she’s a good woman. And she loves community and she loves her people. She is so humane in all her flaws.

I mean this is a truly breathtaking book – it’s a book where you read the words very carefully. I think I may have even read the book and then immediately reread it afterwards. It is very poetic and evocative. And what I love about this book – other than it desperately makes you want to be a better writer – is the way [Anne Michaels] portrays, particularly in Jacob’s story, how memory works and the fragmentary nature of it. It’s also a book about brokenness, and going through the worst of life, and trying to remake yourself after that. How do you reconcile a really difficult past and how do you find joy again?

I remember reading this book and I was, to my great shame, shocked. It has never occurred to me that German people suffered so profoundly. I knew about the mass rapes that happened, but hearing it from her voice, what she went through, what she did to survive – it made me think about understanding what motivates people, but always understanding the other side. Understanding the complexities of history and also not to judge […] Individual histories are really difficult and the choices that individuals make are difficult, and they end up living with them for the rest of their lives.

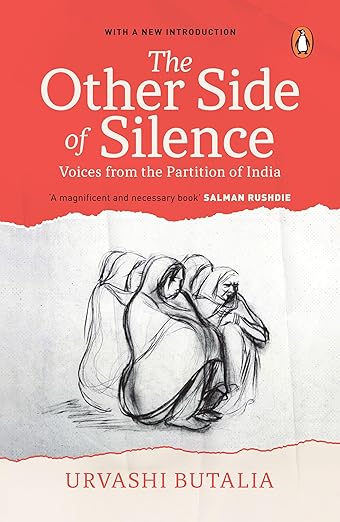

This book came out in the 90s, and there had been literature about partition – but often I find that with really traumatic events the cultural remembrance comes before the actual people can bear to talk about what they went through. And until the 90s that kind of oral history hadn’t really happened in India, in Bangladesh, in Pakistan, and definitely not in Britain from the diaspora community […] There was so much shame and dishonour attached to [what women went through] but Urvashi talks about it, she interviews women and that was really, really remarkable. It was the first time people began to speak about how partition felt to them, in their own voices, and she did it with women.